(AP Photo/Eric Gay)

(AP Photo/Eric Gay)

There is a real crisis at the border right now. It’s a humanitarian crisis, not a security threat. It’s something that the U.S. government is perfectly capable of administering. But it’s still a crisis. It’s taking a toll on migrant families, overworked Border Patrol agents, overwhelmed judges, and humanitarian aid workers.

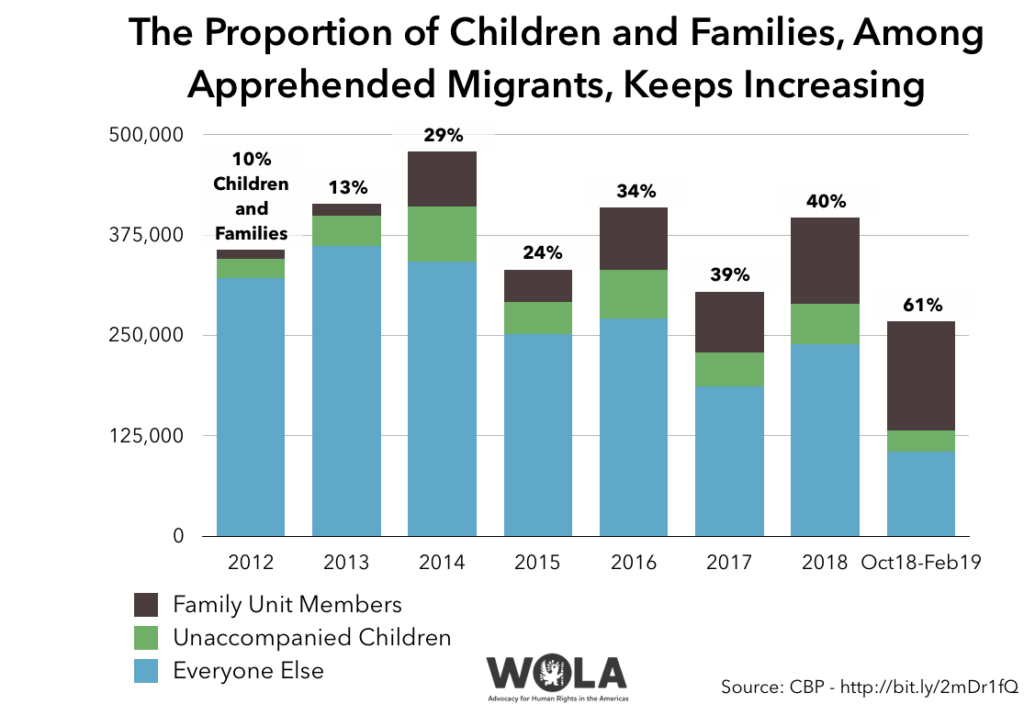

The number of migrants apprehended at the border is no longer near 45-year lows. The U.S.-Mexico border has never seen arrivals of children and parents like it is experiencing now. As recently as 2012, just under 10 percent of Border Patrol apprehensions were kids and families, and at the time, that was considered remarkably high. Now, the proportion of children and parents is about two thirds. This is a stunningly rapid shift.

Most of the arrivals are from two countries. “November of this fiscal year marked the first time that any other country exceeded the numbers of Mexican nationals apprehended and encountered by CBP [U.S. Customs and Border Protection],” the agency’s commissioner, Kevin McAleenan, said on March 5. “Guatemalans and Hondurans are both crossing now in larger numbers than Mexican nationals.” If these high numbers continue, among those apprehended at the border this fiscal year will be 260,000 Guatemalans and Hondurans (making up at least 1 percent of the entire population of Honduras and Guatemala of 26 million people).

Unlike most of the single adults who used to be the majority of migrants, these kids, families, and other asylum seekers aren’t trying to avoid capture. Either they wait until they are permitted to present themselves to CBP officers at land ports of entry, or they cross to where they can touch U.S. soil and wait for Border Patrol to apprehend them.

By international law and U.S. law, anyone who steps foot onto U.S. soil and claims a well-founded fear of persecution in their country on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion, must be given a credible fear interview, to determine eligibility for an asylum hearing before an immigration judge. Unlike “traditional” migrants—single adults seeking to evade capture—this new population of asylum seekers merely wants to reach the U.S. side and await authorities.

Again, this is a phenomenon we’ve only ever seen in the past six or seven years. The Clinton and Bush administrations built walls and a giant post-9/11 border security apparatus, quintupling the size of Border Patrol, with a totally different population in mind.

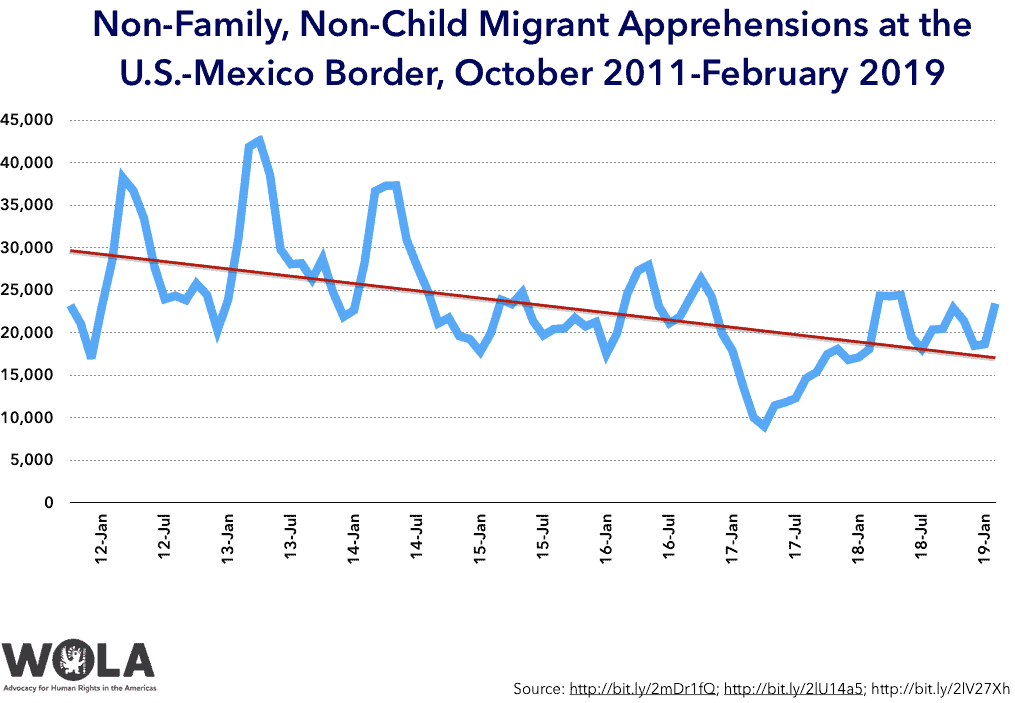

That population—single adults trying to avoid capture, who were mostly Mexican—is still near 50-year lows. Nearly all of the increase is unaccompanied children and family unit members.

Walls are irrelevant to this population. Along the Rio Grande, there is always U.S. soil on which they can stand between the riverbank and any fencing. In the desert, people climb over or dig in sand to tunnel under fencing, then await Border Patrol. Just as walls are irrelevant, so would be any closure of ports of entry, as the president is threatening. “Closing the border,” in fact, could cause more asylum seekers to abandon long waitlists at the ports of entry and present themselves to Border Patrol instead.

This is a new reality, and those who deal with immigration and border issues, including policymakers, need to adjust to it.

Let’s get our minds around it: this is the new pattern, not a temporary surge or distortion. We saw similar child and family waves in spring of 2014 and fall of 2016. Past efforts to “deter” people, including increased enforcement in Mexico, have only managed to lower numbers for a few months. The numbers probably won’t stay this high after the weather gets hot—but we need to act as though this is going to be long-term, and will recur. Because it likely will.

People are coming for several reasons. Usually, a migrant is motivated not by a single factor, but by a combination of these:

A new population requires a new, humane approach. The wave of asylum seekers can be administered, without need for an expensive security buildup. We offer five proposals. Here they are, from north to south, in reverse order along the migrant trail.

1- More courts and judges in a reformed asylum system.

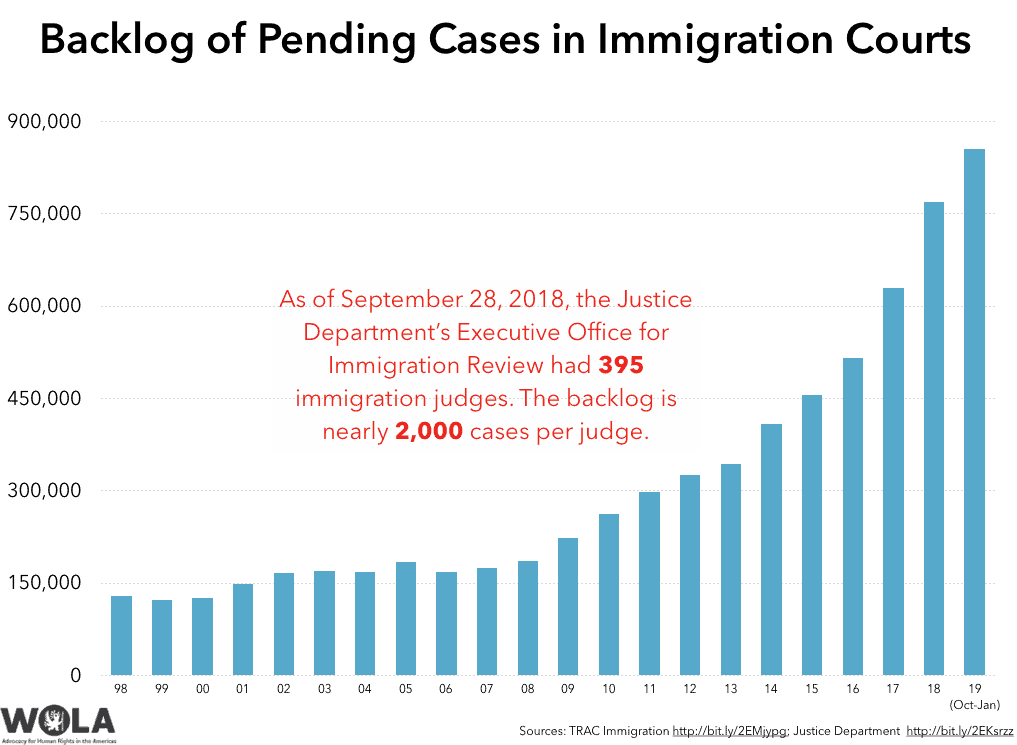

As of January, there were over 850,000 cases in the immigration court system, up from about 300,000 in 2012. As of September 2018, there were only 395 judges to hear them. That’s 2,165 cases per judge. Families who show up right now are being released with notices to appear in courts, after which they are assigned dates as much as four years into the future. In the meantime, they wait in the United States.

How do we resolve this? By putting more resources into administering this new population.

2- Get serious about alternatives to detention, especially family case management.

The United States continues to detain a high number of asylum seekers, including some families, while they await their immigration hearings. This practice further traumatizes individuals fleeing violence and persecution while restricting their access to legal counsel.

Administering the asylum system means ensuring that asylum seekers participate in it fully, with assistance if needed. This can be done without locking them up. Detention should always be a last resort, and shouldn’t apply to families at all. We’re not a country that should pay for locking up families. ICE reported to Congress that family detention will cost $295.94 per family per day in 2020, down (for unclear reasons) from $318.79 in 2019.

The Trump administration should expand, not curtail, alternatives to detention programs. For example, programs that involve caseworkers keeping in frequent touch with asylum-seeking families have brought very high compliance rates for a small fraction of the cost. For $36 per day, an ICE-run Family Case Management Program was achieving a 99 percent compliance rate as a pilot project, with no need for ankle bracelets, until the Trump administration terminated it in 2017. It is high time to evaluate this experience, make any modifications to a revived program, and expand it across the country to manage this new population of asylum seekers awaiting their hearings.

3- Massively revamp our ports of entry.

Ideally, asylum seekers should just be able to present themselves to CBP officers at land ports of entry, instead of wading across the Rio Grande or jumping the wall. The opposite happens right now: asylum seekers are waiting for weeks or months in nearly all Mexican border towns for their turn to approach ports of entry that allow in only a handful each day at best.

One justification the government uses for its “metering” system to limit the number of daily asylum seekers is “capacity”: either a lack of holding space or personnel, or perhaps both. Our ports need to be modernized so that such long waits will be unnecessary: asylum seekers should be steered from rural sites toward the ports, not the other way around. That means filling staffing shortfalls, estimated at about 4,000 CBP officers, and infrastructure needs, estimated at about $5 billion.

This is important to speeding the asylum process and making it safe, orderly, and predictable. It’s also needed for drug interdiction since over 80 percent of all drugs except cannabis are seized at the ports of entry.

4- Recognize Mexico’s efforts to support Central American migrants and expand access to asylum.

The López Obrador administration has affirmed that it will respect the rights of migrants traveling in its territory. It is promoting a joint response to migration flows, focused on shared responsibilities and actions, particularly on economic development, by the governments of Central America, Mexico, and the United States. It has announced its intention to expand Central Americans’ ability to live and work in Mexico, while representatives of Mexican business associations point to labor shortages in parts of the country that migrants could fill.

While apprehensions dropped during the first three months of López Obrador’s government, this was likely due to the number of migrant caravans traveling through Mexico and the government’s decision to issue over 13,000 humanitarian visas to these individuals so that they could live and work in Mexico for at least one year. In February 2019, Mexico apprehended 9,155 Central Americans traveling through Mexico, only a slight drop from the 10,919 it apprehended in this same month in 2018. There continue to be concerns about treatment and effective screenings for protection concerns for migrants in detention.

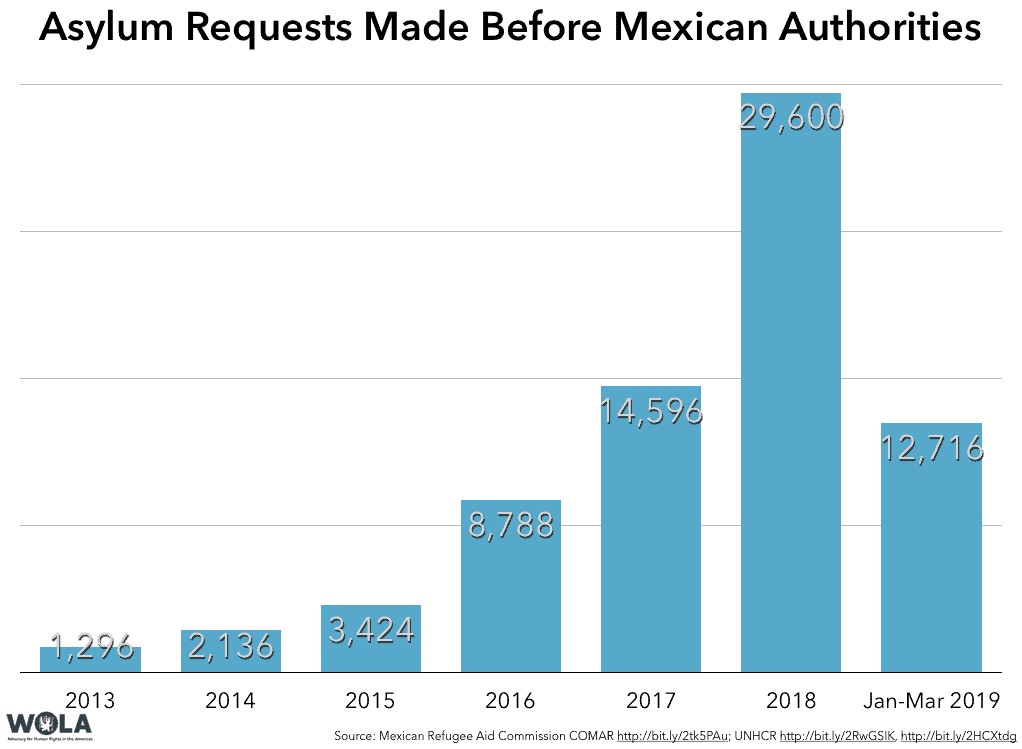

Apart from providing legal ways for migrants to live and work in Mexico, the Mexican government has affirmed a commitment to expand access to asylum in the country. Asylum requests in Mexico almost doubled from 2017 to 2018, and the UNHCR’s conservative projections suggest at least 47,000 asylum claimants in Mexico for 2019, up from 29,600 last year. Mexico’s Commission to Support Refugees (COMAR) received over 12,700 asylum requests in the first 3 months of 2019. While requests are rising, without support from UNHCR Mexico’s asylum system would not have the capacity to process more than a tiny fraction of cases of individuals seeking protection on an estimated 2019 budget of a mere $1.2 million.

Rather than bashing Mexico for not doing enough to address Central American migration (or recognizing Mexico for its enforcement efforts, depending on the day of the president’s tweet), and rather than enacting illegal programs that force many non-Mexican asylum seekers to wait in Mexico while their cases move through U.S. immigration courts, the Trump administration should follow Mexico’s lead and address the root causes of migration from Central America while expanding, not limiting, access to protection in the United States.

Both countries should also work together and with the UNHCR to ensure that a procedure is in place to support Central Americans at risk who deem that the United States is the most appropriate place for them to request asylum, either due to family ties, concerns about safety in Mexico, or other reasons. This is particularly the case for unaccompanied children who may qualify for asylum in Mexico but who have parents or other family members in the United States.

5- Contribute to efforts to make Central America a place people don’t need to flee.

There is no magic solution to the endemic insecurity, violence, poor governance, and poverty in Central America. These are difficult problems that will require a long-term, sustainable strategy and the political will and commitment of Central American governments. There are lessons of a decade of aid since the Central America Regional Security Initiative (CARSI) began. We’re not following all these lessons right now.

If these five recommendations were to become policy, we’d be close to fully addressing the humanitarian crisis, a situation in which:

Many of these proposals will take years to go online and then yield results. The crisis is now. In the short term the United States should:

The Trump administration has offered no shortage of proposals—shutting the border, cutting aid to Central America, and expediting deportations—that will only make matters worse. Those are the virtual opposites of the humane, orderly administrative approach that WOLA recommends here. The White House would double down on a security-focused, punitive strategy designed for countering criminals at the border, not for managing arrivals of children and parents.