(AP Photo/Cedar Attanasio, File)

(AP Photo/Cedar Attanasio, File)

In early May, the Trump administration sent Congress an “emergency supplemental appropriation request,” a call for $4.5 billion in extra 2019 money for operations at the U.S.-Mexico border. The Senate Appropriations Committee will meet to debate, and probably approve, this legislation on Wednesday, June 19. The request language is here (PDF). More usefully, the administration’s table breaking down what it wants the money for is here (PDF).

There is a humanitarian crisis at the border whose dimensions go beyond what was anticipated when relevant U.S. agencies got their 2019 funding. Since October, Border Patrol and Customs and Border Protection (CBP) have apprehended or admitted over 400,000 children and parents seeking protection in the United States, a number that dwarfs previous years. These kids and families are being crammed into short-term processing facilities designed for what until recently was the typical migrant: single adults. The conditions are medieval and inhumane. There is an urgent need to appropriate funds to deal with this new challenge, in a way that helps ease the humanitarian situation.

Of the $4.5 billion in the “emergency supplemental” request, about $3.4 billion seems to be addressed to the real humanitarian situation on the ground. It’s far from perfect, but it is needed. Unlike most things we’ve seen coming out of the White House, this part of the request doesn’t look like it came from Stephen Miller’s desk. It doesn’t have border-wall money in it. Unlike what we’ve become accustomed to, those $3.4 billion don’t seek to make life miserable for migrants, and could be used to support policies and pay the cost of treating them more humanely.

The $3.4 billion deserves quick and serious consideration in Congress, because this year’s flow of asylum-seeking migrants is way higher than expected, and the Departments of Homeland Security (DHS) and Health and Human Services (HHS) will need additional funding in order to process these numbers of people promptly and humanely.

The other $1.1 billion has more to do with the Trump administration’s hardline measures. It is not necessary and more contentiously political, and Congress should slice it out.

Here’s a breakdown of the good and bad in the supplemental appropriation request, drawing from its table PDF.

While there are concerns that need to be addressed, the need for more space for unaccompanied minors is undeniably urgent. The HHS Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) pays for a network of shelters—most run by non-profits, a growing number run by for-profit groups—to hold children who arrive unaccompanied by an adult, until they can be placed with relatives, guardians, foster homes, or some other arrangement.

Time in these shelters should not exceed a few weeks, though in some cases it stretches into months. (Placement was very difficult last year when the Trump administration required fingerprinting and citizenship checks for relatives picking up children, which discouraged undocumented families from coming to get them. That requirement has been dropped.)

The use of contractors should happen with closer oversight to ensure that children’s best interests are guaranteed during these weeks or months. Oversight is also urgently needed given the thousands of accusations of sexual abuse of migrant children held in ORR custody since 2015. Shelters should be adequate facilities, too—not tent cities.

Funding is genuinely needed right now: over 56,000 children have arrived at the border unaccompanied since October, and the supplemental budget request indicates that shelter capacity may grow to a previously unthinkable 23,600 beds. It costs money to care for unaccompanied kids while they await placement with relatives or others.

When asylum-seeking families are apprehended, most are released into the United States, with a date to appear before an asylum officer—though a growing number are being sent back to Mexico to await their hearings. (And tens of thousands more will be if the U.S.-Mexico agreement on “safe third country” status actually goes through.) It’s a terrible shame that neither this nor past appropriations has enough money for well-run family case management programs to monitor the status of asylum seekers awaiting hearings, or for more immigration court capacity to reduce time in the United States waiting for hearings.

Before families are released, and before unaccompanied children are handed over to ORR, the new arrivals must undergo processing. Even countries with the world’s most generous asylum systems need to receive and process people when they arrive asking for protection.

During humane and manageable processing, officials determine whether arriving individuals have communicable diseases or otherwise need medical attention. They verify family relationships. They do criminal background checks. For those who express fear of return, they schedule a credible fear interview with an asylum officer, who then would determine the possibility of eligibility and set a date to appear in immigration court. During this time, officials must also give the arrivals access to bathing and clothing, a dignified place to sleep, food, hydration, medicine, and childcare. By law, under normal circumstances, processing of unaccompanied children must be completed within 72 hours.

When thousands of asylum-seekers are being apprehended per day, the need just to perform this initial processing creates a huge demand for short-term holding space—usually for just one to three days. It also creates a huge demand for personnel—who need not be law enforcement officers—to carry it out.

Initial processing has been poorly executed—or simply overwhelmed—at this time of high demand. Migrants in U.S. border cities are spending a few days or more packed into small, austere holding facilities designed for what until recently was the profile of nearly all migrants at the border: single males.

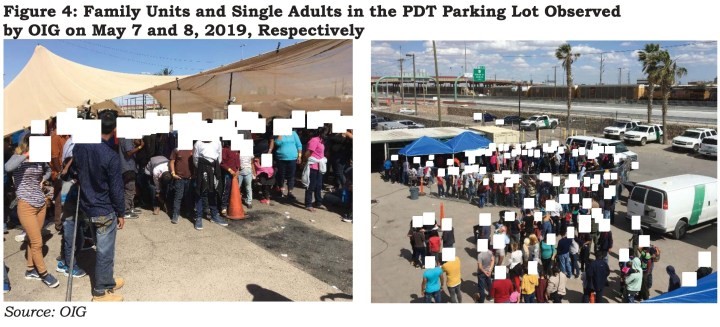

A Homeland Security Department Inspector-General alert published May 30 shows horrific photos of adults packed into the small holding facility next to the Paso del Norte bridge in El Paso, the bridge under which Customs and Border Protection (CBP) held hundreds of Central American families behind a fence for four days in March. (Border Patrol’s El Paso processing facility, which WOLA has visited twice, has less than a dozen holding spaces, each about the size of an above-average office, and clearly designed for single adults.) The report shows dozens of children and parents continuing to be held outdoors in the Paso del Norte facility’s parking lot.

From the Homeland Security Inspector-General’s May 30 alert.

At the official ports of entry (land border crossings), meanwhile, CBP officers continue to limit, or “meter,” the number of asylum seekers who may cross into the United States and present themselves to an officer. This causes asylum seekers to endure weeks-long waits in Mexico, where nearly 19,000 are on precarious waitlists to approach ports of entry—or to cross “improperly” between the ports, where Border Patrol apprehends them.

This is unacceptable and heartbreaking. CBP management says that the agency has employed these measures because it lacks short-term holding space and personnel.

CBP does indeed need more space and personnel for this short-term processing function. However, the space that the agency has built in the past for this purpose has been so spartan and prison-like that it shocks people who see it. The short-term processing facility in McAllen, Texas is where the famously awful “kids in cages” photos came from. A more humane solution should provide more dignified conditions.

The description in the supplemental budget request, and in the 2019 Homeland Security budget law, hints at somewhat better conditions—blankets, showers, appropriate temperatures and “avoid[ing] chain-link fence-type enclosures”—but Congress will need to make sure that asylum seekers are being treated like humans, with adequate medical treatment, during what should be a two or three day stay in these facilities. Since September, at least six children have died shortly after being apprehended by U.S. border authorities and held in temporary facilities. On May 20, a 16 year old boy died after being diagnosed with the flu. It was later discovered that 32 others from the same holding facility in McAllen, Texas positively tested for the flu and were subsequently quarantined. Improved facilities and more, appropriately trained personnel could forestall further tragedies.

Furthermore, it is disappointing that the solution chosen in the request is tent cities—what it calls “soft-sided facilities.” While such structures may be the only way to build capacity right now, in a matter of weeks, it also tells us that DHS still assumes that the asylum seeker flow is a temporary problem that might go away. It’s not clear why DHS thinks that, since numbers of children and families began to increase in 2012-13. This year so far, 66 percent of apprehended migrants have been children and families. We are now in the third, and largest, big wave of children and families fleeing Central America since 2014. This is normal now. Numbers may decline during the hot summer months, or as a result of Mexico’s increased enforcement, but they’ll go up again.

While what’s proposed here is barely adequate for the next few months, the border still needs a short-term processing-space and personnel solution that is more stable than this. Congress must ask CBP what it would cost to build more permanent short-term processing facilities in each border sector—with enough capacity to make it possible for asylum seekers just to show up at ports of entry, and be taken there.

That cost estimate should include paying non-law enforcement personnel—ideally, human services contractors trained in working with children and trauma survivors—to handle processing and care while the asylum seekers are in this short-term custody. Troublingly, the supplemental budget request includes funding only for federal workers temporarily reassigned to processing facilities to fill gaps. That may be the fastest way to get personnel in place for now, but a long-term response will require a different profile.

Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detention beds are a deal-breaker for Democrats, and it’s perplexing that the administration added it when it so desperately needs money for the priorities listed above. ICE’s claimed need for detention space—bringing the daily detained population to a stunning 54,000—is a result of its increased detentions of non-criminal undocumented people in the U.S. interior, and the agency’s insistence on detaining nearly all single adult asylum seekers. Detain fewer non-criminal aliens, as the Obama administration did during its second term, and submit more adults to alternative detention, and the need for additional detention beds goes away.

![]()

This would pay to sustain, probably through the end of the year, “Operation Guardian Support,” President Trump’s deployment of about 2,100 National Guard troops to the border. Like Trump’s separate midterm election-season deployment of a few thousand active-duty troops, this troop surge responds more to a political desire to “look tough” than to any national security issue.

The Guard personnel are mainly playing supporting roles, like maintaining vehicles or repairing fences, or performing surveillance duties: if they see something, they alert Border Patrol. The main justification for Operation Guardian Support is that CBP and Border Patrol are so occupied with caring for and processing asylum seekers that they cannot perform these supporting tasks on their own. If so, then—as discussed above—it’s time to hire civilian personnel or contractors, with skills appropriate for working with trauma victims, to take that load off of CBP officers and Border Patrol agents.

This detention money would pay to hold even more migrants without adequate due process in U.S. Marshals custody as they await, or serve, federal criminal sentences for improper entry into the United States. It would further beef up “Operation Streamline,” which prosecutes and imprisons people who cross the border between the ports of entry. Human rights groups have repeatedly criticized Streamline for its weak due process guarantees, its harshly punitive nature, its clogging of federal courts, and its uncertain effect on recidivist border crossing. Congress should never appropriate money for this program.

Increased capacity “to investigate transnational criminal organizations involved in human smuggling and trafficking” is important, as long as due process safeguards are in place. There have been few high-level prosecutions of these networks or the corrupt structures that enable them. Troubling here, though, is the mention of “rapid DNA test kits.” The ACLU and other organizations have warned about dire privacy consequences of U.S. government agencies possessing copies of non-criminal individuals’ genome data.

Congress should reject $23 million of the proposed money in this category. That portion would pay for a new Trump administration initiative to have asylum seekers give their initial “credible fear” interviews to Border Patrol agents. That’s like having an arresting police officer act like a judge and grand jury. “This program will turn the credible fear screening process into an absolute farce,” Human Rights First argued, as Border Patrol agents lack the legal knowledge and country expertise to conduct these interviews. As frequent statements from the union representing at least three quarters of agents indicate, Border Patrol culture is very skeptical of asylum seekers’ claims, and there is a risk that agents performing the interviews may pre-judge them.

However, some items in this category are too vague to judge. It makes sense to be skeptical about the remaining $155 million in this category. Border Patrol retention incentives could make it unnecessary to hire new agents, which is fine if that’s how it works. It’s not clear what the ICE payroll shortfall issue is. Improved IT systems should help facilitate family reunification and prevent future forced family separation and long-term detention.