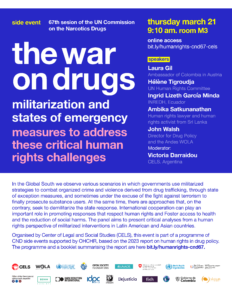

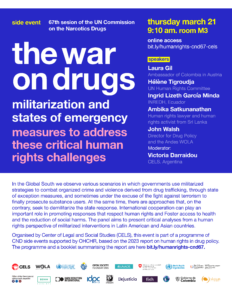

Side Event at the United Nations 67th Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND)

Vienna, Austria

March 21, 2024

Remarks by John Walsh, WOLA

John delivered these remarks as part of the CND side event “‘The War on Drugs,’ Militarization, and States of Emergency: Measures to Address These Critical Human Rights Challenges.” The side event was organized by the Centro de Estudios Legales y Sociales (CELS) with the support of Colombia, Czechia, Paraguay, Switzerland, Uruguay, the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (UNHCR), the World Health Organization, the Centro de Estudios de Derecho Justicia y Seguridad, Elementa Derechos Humanos, the Federación Internacional por los Derechos Humanos, Harm Reduction International, the International Drug Policy Consortium, the Fundación Regional de Asesoría en Derechos Humanos, Open Society Foundations, the Skoun Lebanese Addictions Centre, Students for Sensible Drug Policy International, and the Washington Office on Latin America.

The word “war” is often deployed as a metaphor to indicate urgency and society-wide mobilization for a cause, such as the 1960s “War on Poverty” in the United States.

The “War on Drugs” has never been just a metaphor, and Latin America has been one of the primary theaters in which this very real war has been waged. Like most wars, the primary casualties are civilians.

It’s crucial that the Office of the High Commissioner of Human Rights (OHCHR) is shining a light on the problem of militarized drug control and human rights violations.

Drug prohibition and militarized enforcement are an especially toxic mix from the perspective of human rights.

At least five dimensions shape the dynamics of militarized drug control in Latin America.

- Internal security roles and missions are not new for many Latin American militaries. The Cold War saw the rise of the “national security state” with security forces focused on repressing the “enemy within” and giving rise to massive human rights violations.

- There is a long history of uncertain civilian control over the military, in part a legacy of the Cold War, but with deeper roots. Even where the armed forces do not intervene to depose civilian leaders and take power, accountability to civilian authorities, including the administration of justice, is incomplete at best.

- The armed forces’ identification as guardians of national sovereignty tends to resonate with the public, and civilian political leaders can be tempted to benefit from that popularity by involving the military in public security—including drug control—especially when citizens are fearful and looking to the government for solutions. If drug enforcement comes to be seen as a political priority and as a political imperative, scrutiny and accountability for human rights abuses becomes even more difficult.

- Military roles in drug control are also often promoted and funded by foreign governments. In Latin America, this has largely been a question of U.S. military aid under the banner of the “war on drugs.” With the end of the Cold War, the drug “threat” became at least a partial replacement for anti-communism as the rationale for internal security missions, in cooperation with the Pentagon’s Southern Command, and focused on the Andean region, most notably Plan Colombia. After 9/11, the drug war merged with the war on terror.

- The aims of foreign governments and the local militaries they fund may not align. For example, the United States and other governments in significant consumer markets typically fund enforcement in major producer and transit countries with the aim of curbing drug supplies and reducing drug availability on their streets. Local militaries may be happy to receive aid but may not share the same goals; preventing illegal drugs from reaching other countries might—and should—take a back seat to more immediate local needs. And of course, elements of security forces—as well as politicians and important economic actors—may themselves become engaged in the illegal drug trade.

With these dimensions in mind, the consequences of militarized drug enforcement must be understood within the context of the dynamics created by drug prohibition.

- Our collective attempt at prohibition makes drug use more hazardous while generating vast revenues that fuel organized crime and corruption worldwide. While governments tend to describe enforcement as “combatting drug trafficking,” in reality the underlying policy of prohibition has led to burgeoning illegal drug markets that continuously generate enormous profits for groups and individuals willing to act outside the law.

- Military force and militarized enforcement are ill-suited to respond to lucrative illegal markets. The perverse outcomes of such enforcement operations—such as “kingpin” strategies to remove leaders of trafficking organizations—end up splintering drug organizations, multiplying the challenges to supply control, and triggering spirals of violence. These consequences may be unintended, but they are no longer unpredictable since enforcement has clearly failed to curb supplies and has for decades fueled corruption, conflict, and violence.

- Civilians are the people caught in the crossfire. Worse, lines blur as elements of security forces also coordinate operations with drug traffickers, creating chaotic circumstances and making accountability for abuses even more difficult to achieve.

- Especially where governments formally declare the existence of internal armed conflicts, appeals to the applicability of international humanitarian law set a low bar to prevent civilian casualties, with the principles of distinction, proportionality, and precaution leaving many civilians vulnerable to harm due to military application of lethal force.

OHCHR has already offered important recommendations in its report released last year:

- Reserve drug law enforcement for civilian law enforcement agencies that are properly trained and equipped.

- Resort to military force extraordinarily, temporarily, and when strictly necessary in specific circumstances.

- Ensure that financial and technical assistance provided for drug enforcement operations does not contribute to human rights violations.

For example, U.S. foreign aid includes the Leahy Law, meant to ensure that military units responsible for abuses cannot receive U.S. aid. Such laws do not implement themselves, but require continuous engagement, information, and pressure from civil society.

Ultimately, addressing the massive human rights harms caused by militarized enforcement of the drug war will require moving beyond the prohibition regime. OHCHR indeed has also suggested that countries should explore how to achieve the responsible legal regulation of psychoactive substances.

This step can seem daunting since the prohibition regime has put down deep roots, politically, bureaucratically, and ideologically, and has created powerful vested interests that defend the status quo.

But we should remember that the prohibition regime is a relatively recent construction in our history—just the space of my own lifetime—and arose from choices made by governments at a very different time.

If the prohibition regime ever was fit for purpose, nearly seven decades of experience and evidence have made clear that prohibition is not only failing to meet its stated aims but is causing massive harm. Those harms are increasing, not declining, underscoring the urgency of choosing to leave prohibition behind to support human rights.