With this series of weekly updates, WOLA seeks to cover the most important developments at the U.S.-Mexico border. Since what’s happening at the border is one of the principal events in this week’s U.S. news, this update is a “double issue,” longer than normal. See past weekly updates here.

Subscribe to the weekly border update

Support the Beyond the Wall campaign

Pressure grows to end Title 42

The Biden administration continues to apply “Title 42,” a public health order that the Trump administration put into place at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020. As implemented, Title 42 allows Border Patrol to expel migrants it encounters back to their countries of origin—or, if they are Salvadoran, Guatemalan, or Honduran, back into Mexico. In most cases, expulsion occurs in as little as an hour or two. In nearly all cases, it occurs without migrants getting any chance to ask for asylum or other protection.

Over 85 percent of single adult migrants and about a third of migrants arriving as families with children are expelled. The Biden administration is not expelling children who arrive unaccompanied, unless they are from Mexico (and a court prohibited the Trump administration, too, from expelling children during its last two months). CBP is flying Central American families every day from south Texas—where Mexico has placed limits on expulsions—to El Paso and San Diego, then expelling them there.

“By sending asylum seekers back to danger without asylum assessments, the administration fails to protect refugees and blatantly violates U.S. refugee laws and treaties,” reads a report published on April 20 by Human Rights First, Al Otro Lado, and the Haitian Bridge Alliance. The product of a big team of researchers, the 33-page document offers an up-to-the-moment view of the suffering that the Biden administration’s application of Title 42 is causing. Failure to Protect is a very informative, but brutal, read.

Its most alarming topline finding: “Human Rights First has tracked at least 492 attacks and kidnappings suffered by asylum seekers turned away or stranded in Mexico since President Biden took office in January 2021.” The organizations count 17 countries, from Russia to Venezuela to Somalia, whose citizens have been expelled since Biden was sworn in. Since February 2021, 27 expulsion flights have sent 1,400 adults and children back to Haiti.

Among the report’s many alarming examples:

- “In February 2021, a 37-year-old asylum seeker who fled Haiti after being kidnapped, beaten, and raped because of her involvement with a political opposition group was expelled to Haiti with her husband and baby, where they are now in hiding.”

- “Nicaraguan authorities detained a Nicaraguan political activist, her husband, and seven-year-old child for 11 days, interrogated, and beat the couple after CBP expelled the family along with approximately 200 other Nicaraguans in June 2020.”

- “Nine- and fourteen-year-old Honduran children were kidnapped with their asylum-seeking mother in Monterrey in March 2021 after CBP expelled them three times since December 2020.”

- “In February 2021, a Guatemalan woman who had been expelled by CBP to Mexicali after attempting to seek asylum was raped in Tijuana.”

- “CBP expelled a 15-year-old Guatemalan boy and his asylum-seeking mother to Ciudad Juárez where they had been kidnapped in February 2021. The woman told Human Rights First researchers that when she tried to explain the danger she faced, U.S. immigration officers told her that they didn’t care because ‘the president is not giving political asylum to anyone.’ CBP expelled the family to dangerous Ciudad Juárez at night during a snowstorm after they were held in CBP custody for days without food or water.”

- “At least 20 LGBTQ Jamaican asylum seekers are stranded in Mexico facing violence and discrimination, but they are too terrified to approach the U.S.-Mexico border to request protection for fear they will be immediately expelled to Jamaica where they would face continued persecution.”

The report also includes numerous outrageous accounts of Border Patrol agents’ casual cruelty and aggressive behavior toward migrant parents and children—so many that they could form a separate report.

The organizations highlight the painful trend of expelled families deciding to separate inside Mexico, sending children back across the border unaccompanied, where they might end up in immigration proceedings inside the United States, perhaps living with relatives. Mounting evidence points to these Title 42-induced family separations happening more often than we had imagined. Citing secondary sources, the report reads:

16 percent of unaccompanied children screened by Immigrant Defenders Law Center between December 2020 and March 24, 2021 had traveled to the border with a parent or other family member who was blocked from seeking protection with the child due to the Title 42 expulsion policy. In April 2021, a Border Patrol official told CNN that more than 400 unaccompanied children taken into custody in South Texas had previously tried to enter the United States with their families.

More accounts of Title 42-related family separations surfaced this week in reporting by KPBS in Tijuana and the Guardian in Reynosa.

Litigation against Title 42 remains active in Washington, DC Circuit Court. On April 22 the ACLU agreed with the Biden administration on the latest of several extensions of a pause in its lawsuit against the expulsions policy. The court is set to resume on May 3.

Increases in migration appear to be flattening out

For migrant families who don’t get expelled, most U.S. border cities have a charity-run facility that provides a short-term place to sleep, food, clothing, and help with travel arrangements. “Respite centers” like Catholic Charities of Rio Grande Valley, Annunciation House in El Paso, Casa Alitas in Tucson, and the San Diego Rapid Response Network receive asylum-seeking migrants whom Border Patrol or Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) has released from custody, usually with a notice to appear in immigration court.

The expulsion of so many families to Mexico has left these respite centers below capacity, even at a time when U.S. authorities are encountering large numbers. Annunciation House is taking in 30 to 35 migrants per day, even as one or two planeloads of 100-plus migrants each arrives in El Paso each day: the rest are expelled into Ciudad Juárez. Sister Norma Pimentel of Catholic Charities told Axios that her shelters in the Rio Grande Valley, the sector where 67 percent of family migrants were apprehended in March, are receiving 400 to 800 migrants, mostly families. That sounds like a lot, but she noted, “I haven’t seen the numbers as high as 2019.” That number, roughly extrapolated border-wide, points to only a minor increase, if any, over the number of family migrants encountered at the border in March.

Indeed, the rate of growth of family and child arrivals seems to have hit a pause in April. Weekly CBP apprehension data seen by WOLA points to Border Patrol’s “encounters” of family and unaccompanied child migrants receding slightly during the first half of April, after more than doubling from February to March. The percentage of families who are expelled into Mexico appears to remain in the 30-40 percent range (this number includes a small number of Mexican families). Encounters with single adults, well over 80 percent of whom are expelled, continue to rise, but at a slower pace than in March.

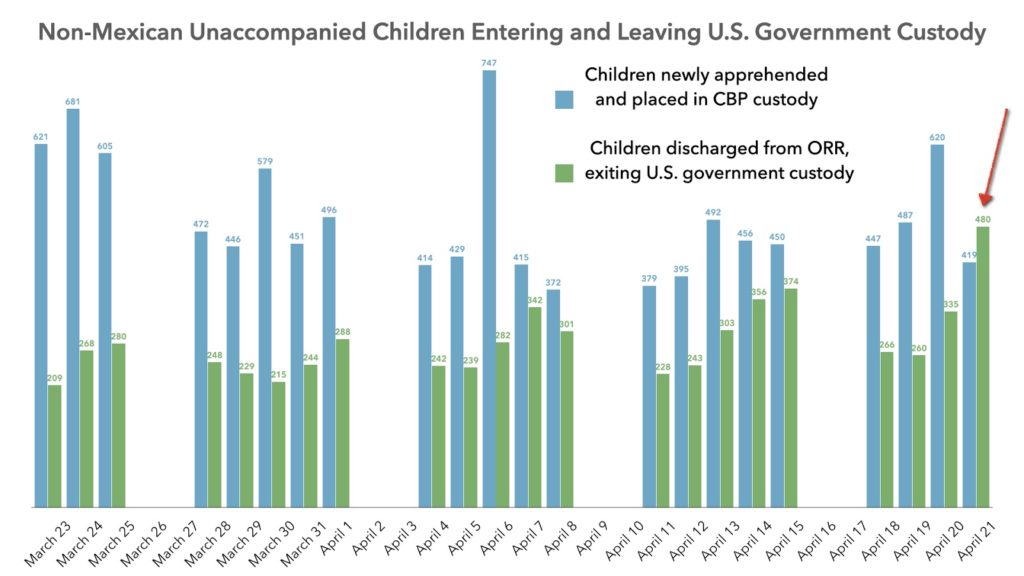

Daily Border Patrol data shows slightly more unaccompanied children arriving at the border this week, mildly reversing a trend of steady declines since late March. There is some good news, though: on April 21, for the first time since the current jump in child migrant encounters began, the number of unaccompanied children in U.S. government custody actually declined. The Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) discharged—placed with families or sponsors in the United States—more children (480) than Border Patrol newly apprehended at the border (419). On this chart, the green exceeded the blue for the first time:

A lull in April doesn’t necessarily mean that this spring’s increase in migration has flattened out for good. There is a pattern. Though spring is usually a time when migration jumps, Border Patrol migrant apprehension data for 2014, 2015, 2018, and 2019 show small April increases sandwiched between larger increases in March and May. The May increases, though, were never larger in percentage terms than March.

As unaccompanied children don’t get expelled, the overall downward trend in child arrivals since late March can’t be ascribed to Title 42 serving as a “deterrent.” An increase in Mexico’s migrant interdiction operations could be contributing: Tonatiuh Guillen, a longtime Mexican migration expert who briefly headed the Interior Department’s National Migration Institute (INM), told the Wall Street Journal that “apprehensions at the U.S.-Mexico border are likely to go down this month in part as a result of Mexico’s actions.” That hypothesis is difficult to prove at the moment, though.

Mexico sends troops and talks trees

The Failure to Protect report calls out Mexico’s government for acceding to the Biden administration’s requests to cooperate with the Title 42 expulsions, noting that doing so “continues to facilitate U.S. violations of international protections for refugees.”

Mexico has also deployed larger numbers of its new National Guard and regular armed forces along its northern and southern borders to interdict migrants. Near Guatemala, the Wall Street Journal reports citing Mexican officials, Mexico has deployed about 9,000 soldiers and guardsmen along with 150 immigration officers from the INM. The immigration agency has installed “dozens of checkpoints” along roads in the southern border states of Chiapas and Tabasco, where agents, accompanied by security forces, are pulling many undocumented Central Americans off of buses, then detaining and deporting them.

At Mexico’s northern border, guardsmen have been stationed at some sites where large numbers of families had been crossing the Rio Grande and awaiting Border Patrol apprehension on the riverbank south of the border wall. (One must be standing on U.S. soil in order to request asylum in the United States.)

Alfredo Corchado of the Dallas Morning News talked to some of the National Guard troops at a frequent crossing point in downtown Ciudad Juárez, where the Rio Grande is barely 10-15 feet wide and shallow, and the border wall looms dozens of yards away. One member of the National Guard estimated that crossings in that area had fallen 70 to 80 percent since his unit was deployed there. He doubted, though, that this has deterred asylum-seeking families.

“We’ve pushed them outside to desolate areas, out in the desert,” he said, conceding their efforts only put the migrants and their children in a more dangerous situation. “The desert doesn’t serve as a deterrence. They, women and children, cross in spite of the rattlesnakes, giant spiders, the hot sun. That’s what poverty does to you. The American dream is so alluring that you risk it all.”

The Failure to Protect report, meanwhile, recalls the human rights dangers associated with increased security-force deployments, which WOLA has documented in much past reporting. “Mexican police, immigration officials and other government authorities are directly involved in kidnappings, extortion and other violent attacks against asylum seekers and migrants forcibly returned by DHS to Mexico,” it reads.

Mexico hasn’t yet reported its migrant apprehension and detention data from March. However, the Wall Street Journal obtained statistics pointing to a 32 percent jump in INM apprehensions of Central American migrants from February to March, to 15,800. U.S. apprehensions of migrants jumped 72 percent from February to March.

UNICEF said that the number of non-Mexican migrant children currently in Mexico grew from 380 in January to 3,500 at the end of March, with 275 minors entering the country every day—some coming from Central America, and some being expelled with parents from the United States. Children make up about 30 percent of the population in Mexico’s migrant shelters, the UN agency reported, and half of them traveled unaccompanied. “These children arrive after perilous journeys of up to two months, alone, exhausted and afraid,” said UNICEF director Henrietta Fore. According to the Mexican daily Milenio, “She explained that at every step they are at risk of violence and exploitation, gang recruitment and trafficking, which has tripled in the last 15 years.”

The INM reported that Mexico will be opening up 17 temporary shelters for child migrants in Chiapas and Tabasco, which will be run by the government’s child and family welfare agency (DIF).

Milenio found that an increasing number of families are migrating without making large payments to smugglers. Instead, more Central American parents with children are walking hundreds of miles and boarding cargo trains, an enormously risky journey. Migrants told the paper that Mexican authorities they encounter are less likely to detain them if they are traveling with children. “Hundreds of migrants believe that they have found in children a way to access certain benefits,” Milenio reports, but “the reality is that they expose them to bad weather, kidnapping, poor nutrition, disease, and the risk posed by La Bestia,” the notorious cargo trains.

This route is very dangerous. On April 20, two Honduran migrants were shot dead, and three more wounded, as they tried to flee a gang seeking to rob them along the railroad tracks, in broad daylight, in a rural zone of Tabasco state.

Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador recorded an April 18 video from Palenque, Chiapas, a town along one of the main train routes. There, he laid out a proposal for cooperation with the United States to address Central American migration. Central American and Mexican migrants seeking to emigrate, he said, should work for three years in Mexico planting trees and other crops in a reforestation program his government calls Sembrando Vida (“sowing life”). Upon completion of this obligation, the United States should grant these migrants a six-month temporary work visa, along with the right to apply for U.S. citizenship.

López Obrador said he would present this plan, which he billed as an environmental initiative, during the April 22 Leaders Summit on Climate virtually hosted by President Joe Biden. U.S. officials did not appear interested in discussing the idea at the summit, however. In response to a question from the Mexican daily Reforma, an unnamed senior U.S. official stated, “This is not a conversation about migration but a conversation about climate change. We are not focused on the interplay of issues.” The official added, “We just recently heard [President López Obrador’s proposal] and it doesn’t sound like it has had a chance to be part of extensive discussions in Mexico or between Mexico and the United States.”

Links

- Vice President Kamala Harris is to talk to Guatemalan President Alejandro Giammattei on April 26, and take part in a virtual roundtable with Guatemalan “community-based organizations” on April 27, Axios reports. She may visit Central America in June.

- The Washington Post and New York Times dig deep into President Biden’s awkward April 16 double about-face on the U.S. government’s annual refugee cap. Susan Gzesh of the University of Chicago points out at Just Security that “almost no Guatemalans, Hondurans, or Salvadorans have ever been welcomed to the United States through USRAP,” the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program.

- The Biden administration has ordered U.S. border and immigration agencies to stop using terms like “alien,” “illegal alien,” and “assimilation” in their communications.

- A group of senators from both parties met on April 21 to discuss how immigration reform legislation might move forward. According to The Hill, “the starting points” are a Republican demand for a “streamlined” asylum process at the border that would reduce the number of unaccompanied children allowed into the United States, and a Democratic demand that so-called “Dreamers” be given a path to citizenship. Judiciary Committee Chairman Sen. Dick Durbin (D-Illinois) led the meeting of four Democrats and four Republicans. At an April 20 meeting with Congressional Hispanic Caucus members, meanwhile, President Biden indicated he might favor allowing immigration reform legislation to go forward under “reconciliation,” Senate rules allowing budget-related bills to pass on a simple majority without a filibuster.

- The process of winding down the Trump administration’s “Remain in Mexico” program, known as Migrant Protection Protocols or MPP, is proceeding slowly. As of the end of March, TRAC Immigration reports, 3,911 of 26,432 Remain in Mexico subjects with pending asylum cases had been allowed into the United States—or at least, had changed their venues away from MPP courts to normal immigration courts elsewhere in the country.

- Republican border-state governors are actively opposing any alteration of the Trump administration’s border and migration policies. Arizona’s governor, Doug Ducey, announced a $25 million deployment of his state’s National Guard to the border, although his state’s border sectors account for only 18 percent of Border Patrol’s migrant encounters since October. Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton, working in tandem with a legal group that former Trump advisor Stephen Miller is billing as the opposite of the ACLU, is suing to force the Biden administration to expel unaccompanied children under Title 42.

- At the Intercept, Ryan Deveraux files a lengthy, multi-source report from Arizona and Sonora. It finds that the Biden administration’s persistent application of Title 42 expulsions “is making one of the deadliest stretches of the U.S.-Mexico divide more dangerous, endangering the people the president purports to support and enriching the illicit networks he purports to oppose.” Many expulsions are happening in the middle of the night.

- About 90 days after the White House launched a 60-day review of the future of Donald Trump’s border wall, “the wall’s future remains in limbo and the review continues” amid increasingly mixed messages, ABC News reports.

- A Vice investigation details how U.S. money-transfer companies profit from ransom payments wired to those who kidnap migrants in Mexico from their relatives in the United States.

- At Talking Points Memo, Tierney Sneed tells the story of how Donald Trump’s Department of Homeland Security (DHS) got over its misgivings and embraced “We Build the Wall,” a private, donor-supported border wall-building project that, prosecutors allege, turned out to be riddled with fraud.

- The Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) shut down an emergency shelter for unaccompanied migrant girls in Houston, after allegations of mistreatment, including telling the girls “to use plastic bags for toilets because there were not enough staff members to accompany them to restrooms.” The facility was run by a non-profit “with no prior experience housing unaccompanied migrant children,” ABC News reports.

- Border Patrol reported encountering a female Honduran migrant “incoherent and in medical distress” in south Texas on the evening of April 15, while with her adult daughter and two young children. The woman died at the McAllen, Texas hospital early the next morning.

Adam Isacson

Adam Isacson