With this series of weekly updates, WOLA seeks to cover the most important developments at the U.S.-Mexico border. See past weekly updates here.

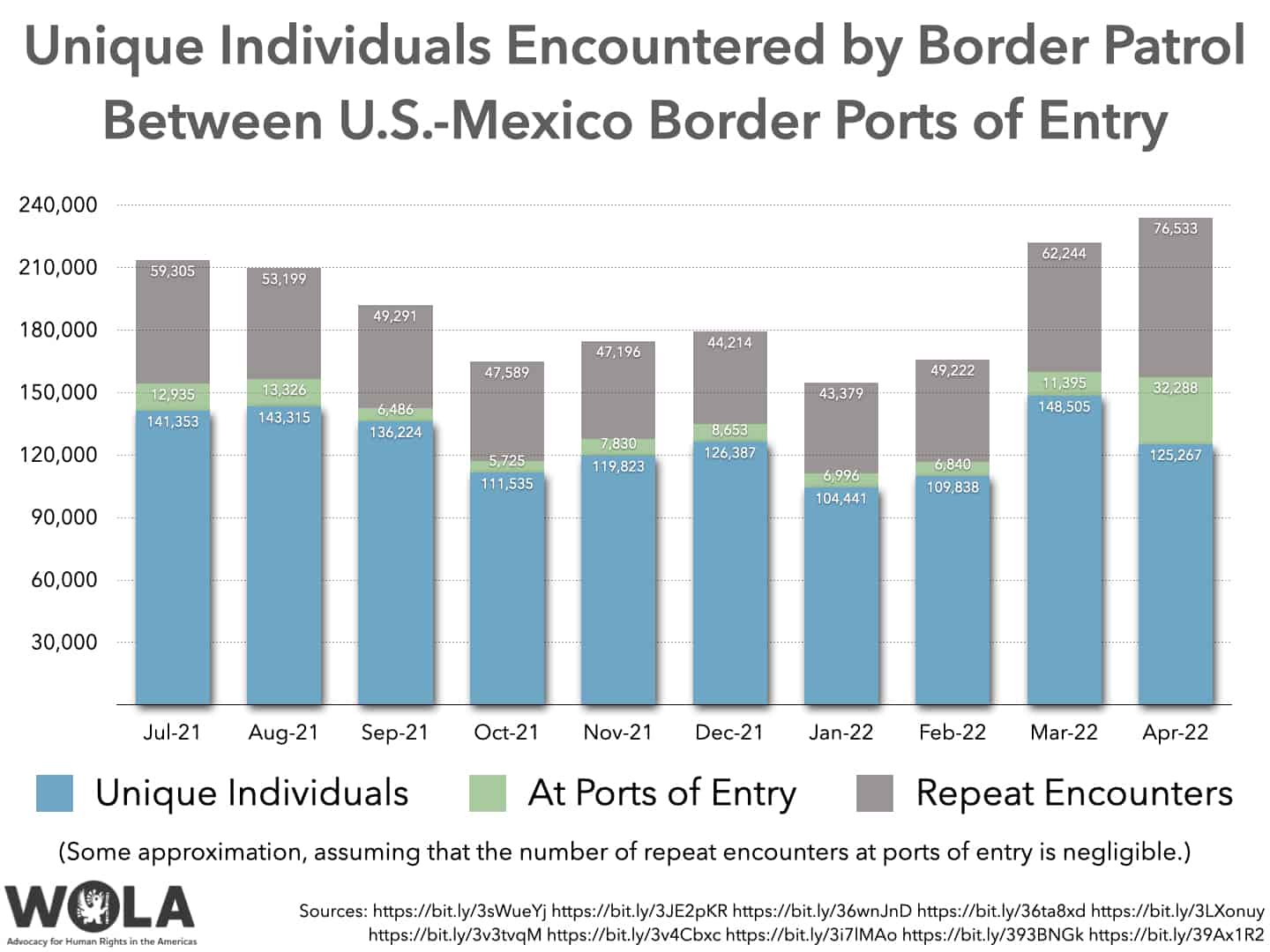

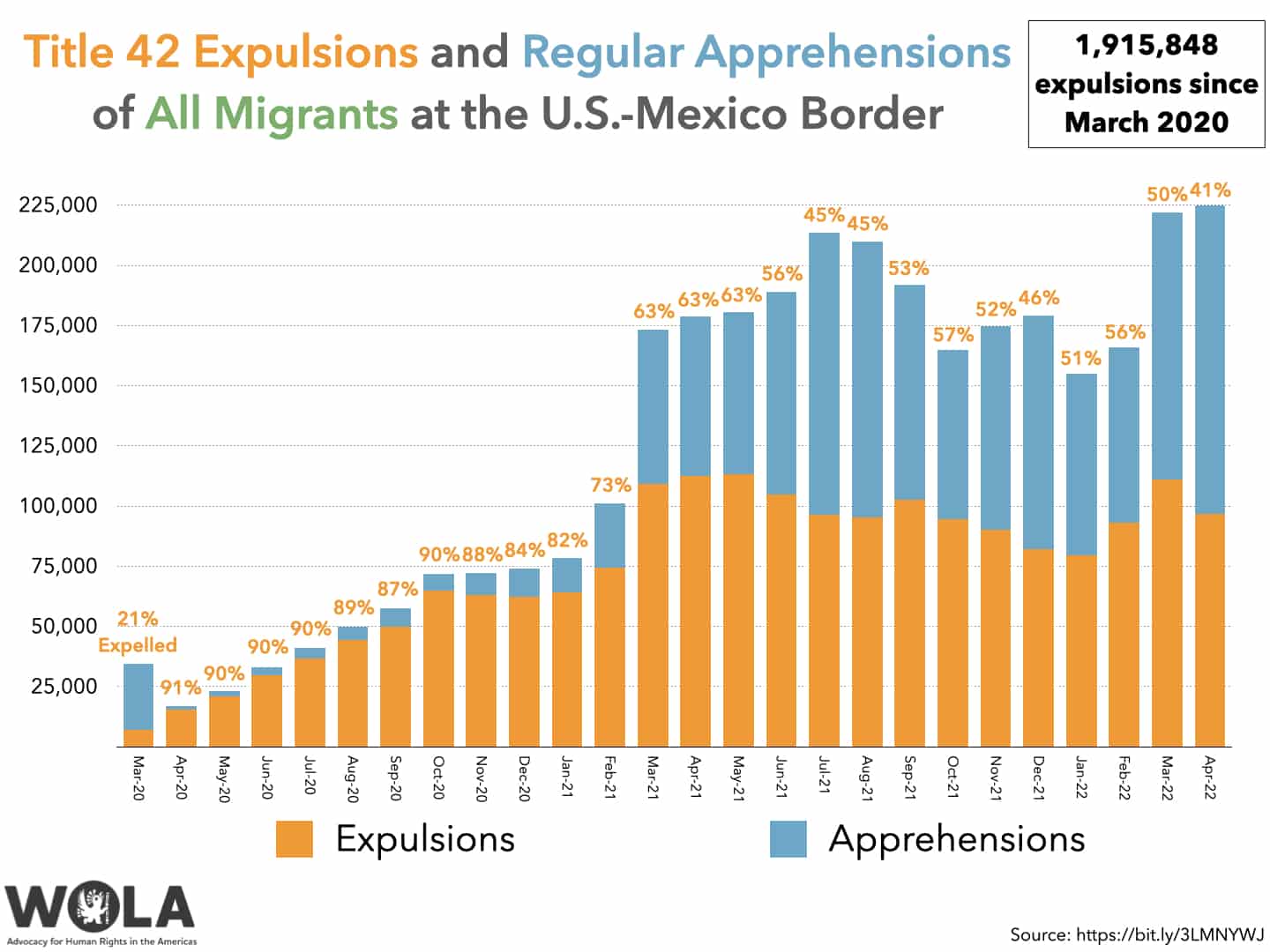

U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) reported data on May 17 about the agency’s encounters with migrants at the U.S.-Mexico border during the month of April 2022. It encountered 157,555 individual migrants on 234,088 occasions, 2 percent fewer individuals than in March. The gap between “encounters” and “individuals” indicates a very large number of repeat crossings, a result of CPB’s rapid expulsions of migrants under the Title 42 pandemic authority, which eases repeat attempts.

Of those 157,555 people, 32,288 reported to the border’s land ports of entry—20,118 of them citizens of Ukraine whom CBP paroled into the United States. Since repeat encounters are rare at ports of entry, subtracting 32,288 from 157,555 leaves a total of about 125,267 individual migrants apprehended by Border Patrol between the ports of entry in April. While high, this “unique Border Patrol apprehensions” number is 16 percent fewer than it was in March, and is 6th for the last 10 months, the period during which CBP has reported unique individual apprehensions.

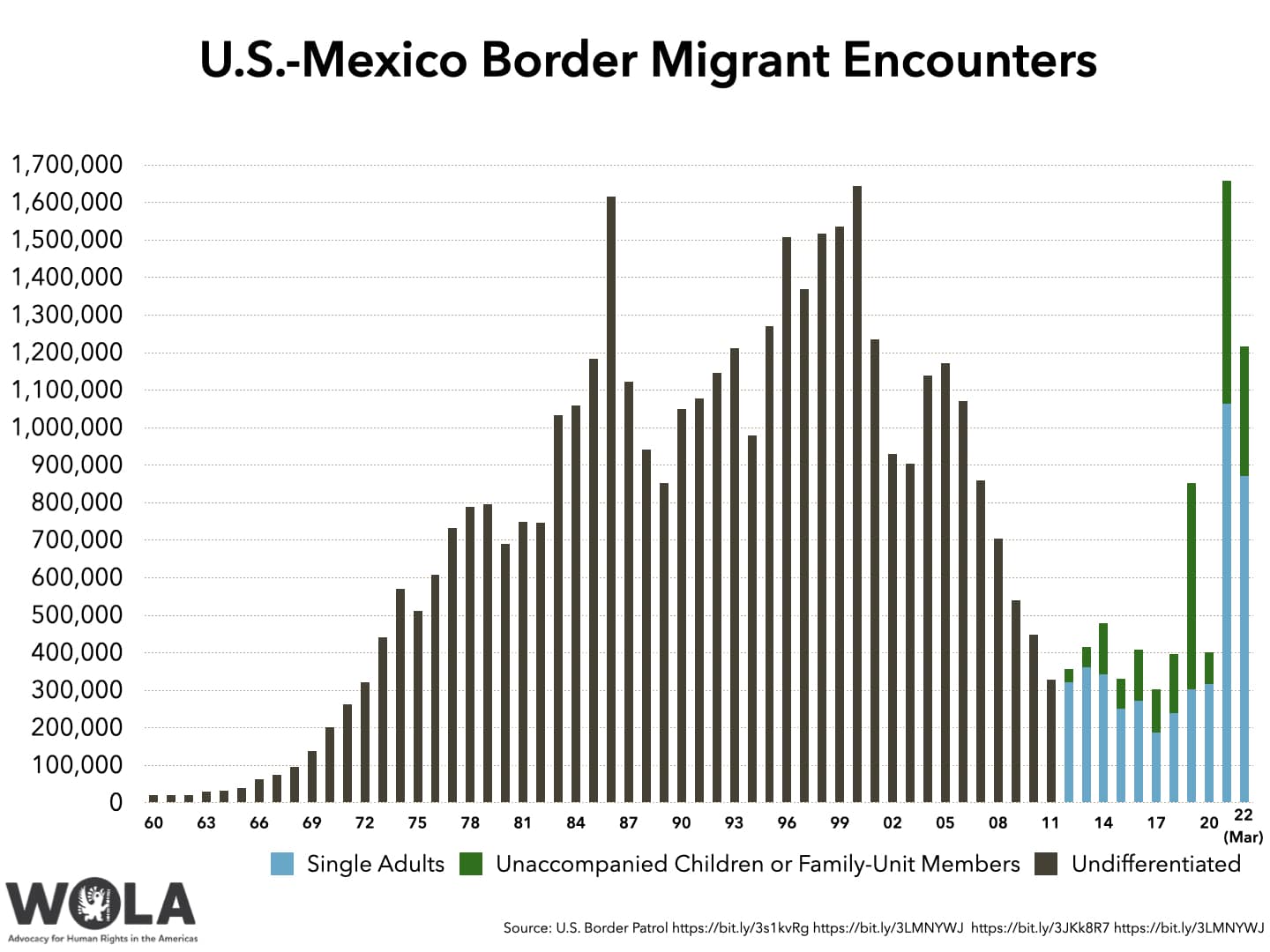

April brings CBP’s overall “encounters” number to 1,478,977 since fiscal year 2022 began last October. As five months remain to the fiscal year, the agency is likely to break its annual migrant encounter record.

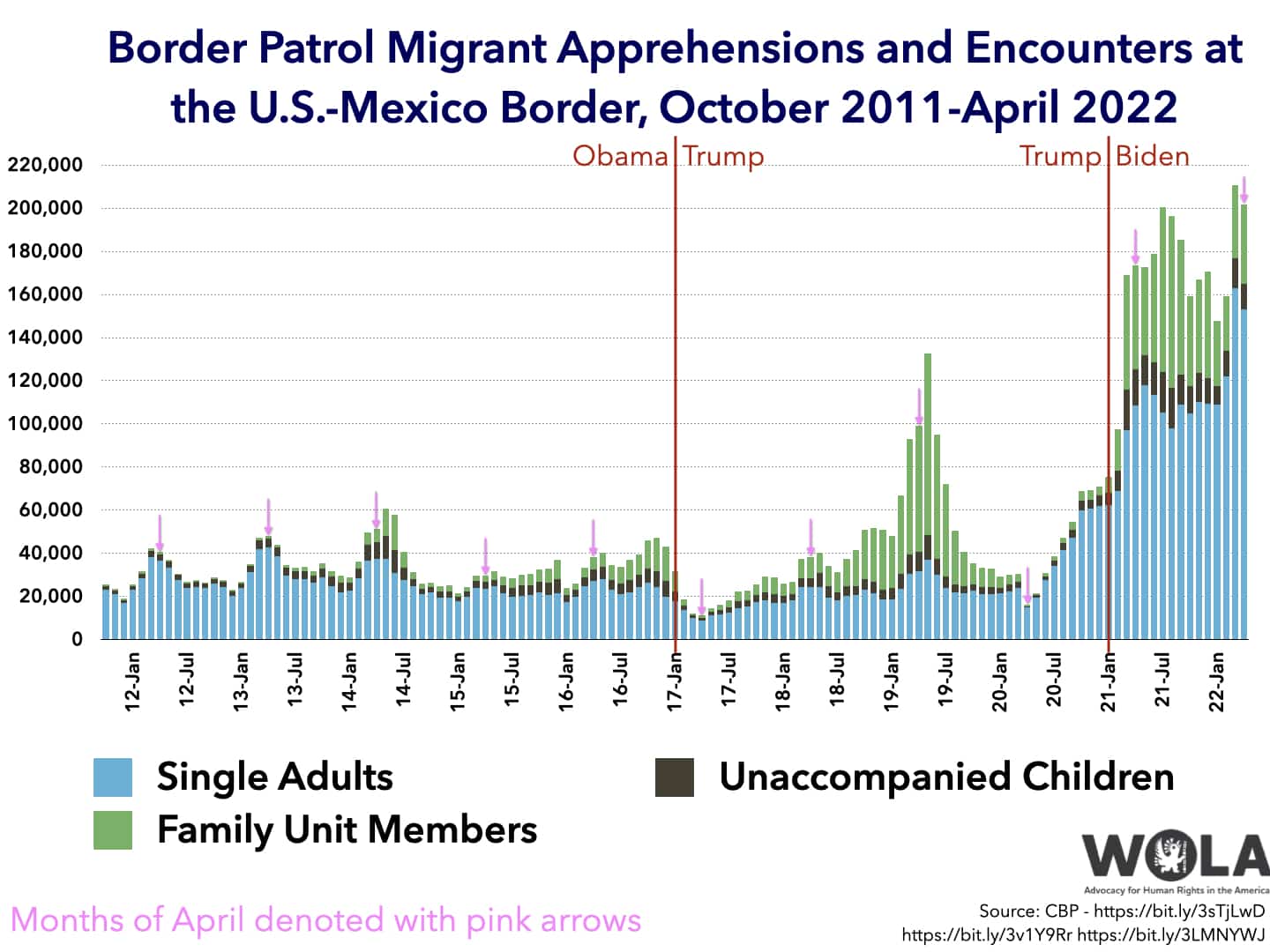

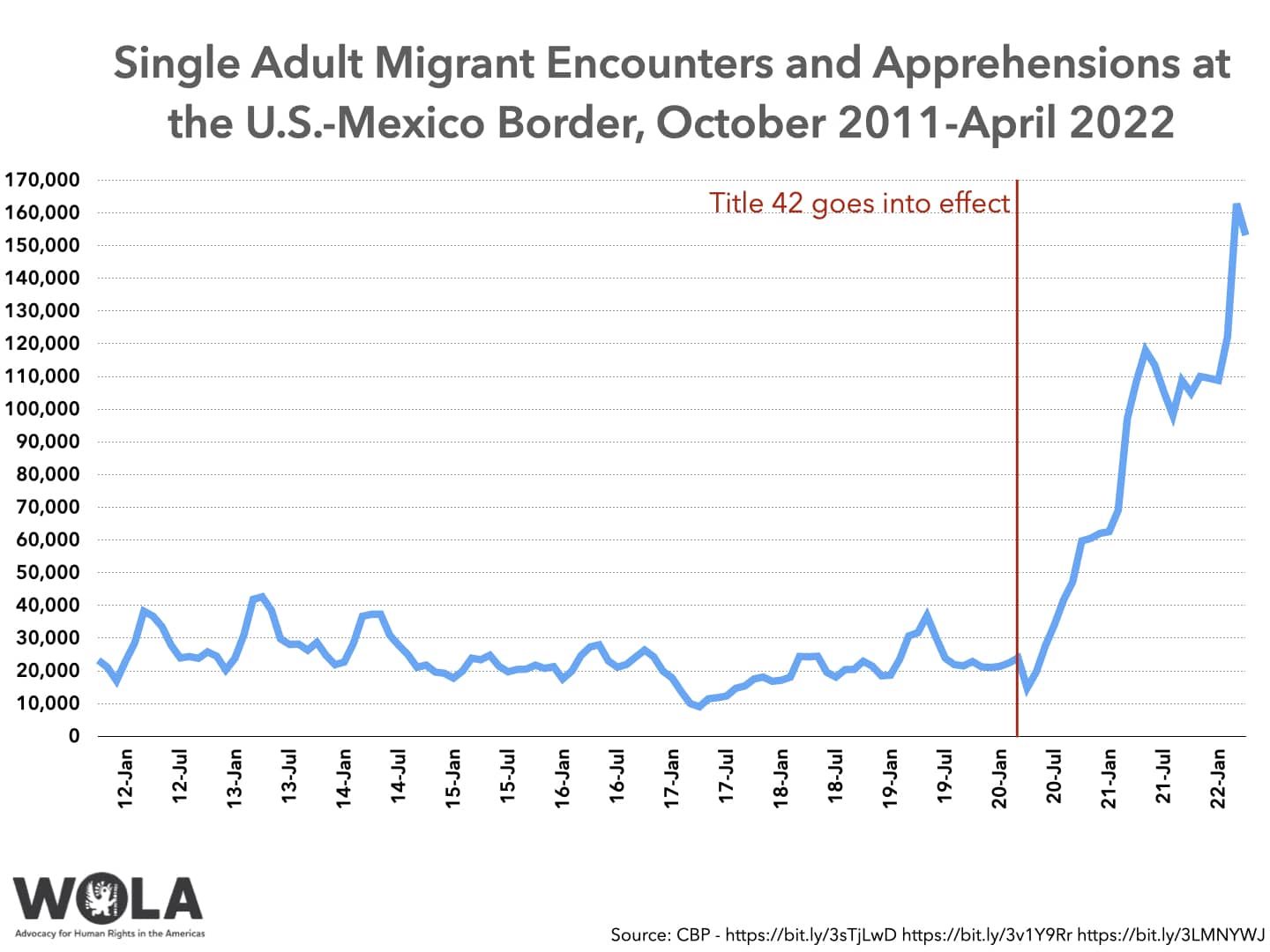

72 percent of migrants encountered at the border so far this year are single adults. Other than the pandemic year of 2020, this is the largest proportion of single adults since 2015. April continued the trend, with 71 percent of the month’s encounters occurring with adults traveling without children.

Adults are more likely than families or children to attempt repeat crossings, so Title 42’s easing of repeat attempts has inflated this number. Should Title 42 end, DHS officials say that they are prepared once again to apply “consequences” like immigration bans and even prison time to repeat crossers. As a result, they expect the number of repeat crossings—and thus the overall “encounters” number—to decrease after Title 42 comes to an eventual end.

Title 42 may or may not end on May 23, as this update discusses below. By that date, it’s somewhat likely that the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) will have used the authority to expel its 2 millionth migrant. The expulsions total at the U.S.-Mexico border stood at 1,915,848 on April 30.

CBP used Title 42 to expel 41 percent of migrants (and 54 percent of single adult migrants) whom its personnel encountered in April. Another 7 percent were processed under normal immigration law, but then removed from the United States. Of the remainder, 110,207 were released into the United States, in many cases to pursue asylum claims, and 7,782 were handed over to Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).

The 41 percent of migrants expelled under Title 42 is a somewhat smaller proportion than in earlier months, in large part because an ever larger share of migrants are coming from countries whose citizens the U.S. government cannot easily expel, like Cuba, Ukraine, Colombia, Nicaragua, or Venezuela.

In fact, Cuba and Ukraine were the number two and three countries of origin of migrants encountered at the border in April, a circumstance that is unlikely ever to repeat now that Ukrainian citizens have a more formal process to petition for refuge in the United States. The elevated number of Cuban arrivals at the border owes in large part to Nicaragua’s November decision to eliminate visa requirements for visitors from the island, making the journey much shorter.

Until 2018, 95 percent of migrants apprehended at the U.S.-Mexico border routinely came from four countries: Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. In 2019, that dropped to 91 percent. In April 2022, those four countries’ share of all migrant encounters declined to 54 percent. Still, the four made up 99 percent of all Title 42 expulsions last month. This is because Mexico accepts Title 42 expulsions over the land border of its own citizens, and of citizens from the three Central American countries (and as of early May, some citizens of Cuba and Nicaragua).

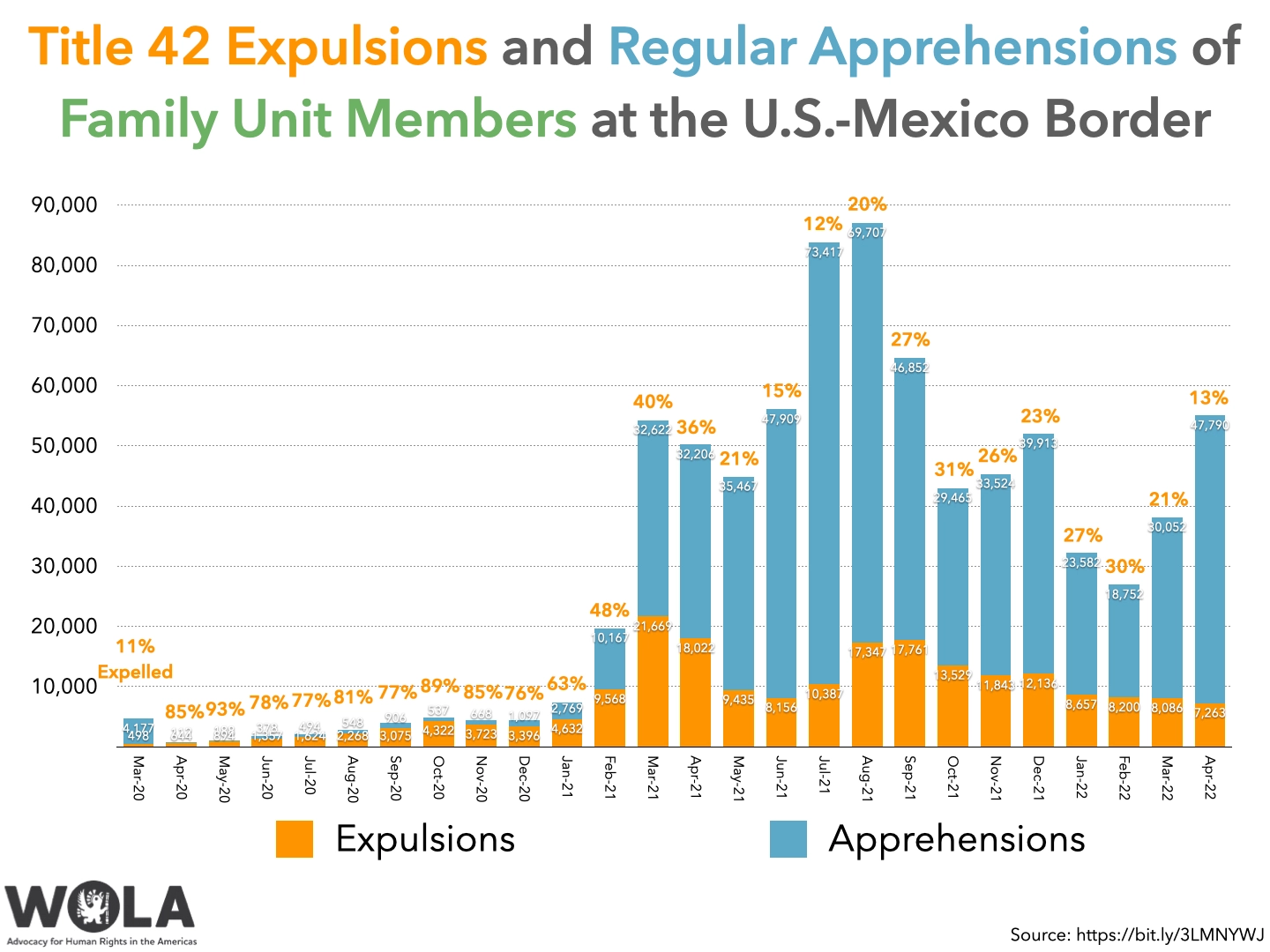

Encounters with migrants traveling as families (parents with children) increased 44 percent from March to April, though they remain significantly fewer than they were in 2019 and during the summer of 2021. A remarkable 72 percent of families encountered in April were not from Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, or Honduras. Largely as a result, 13 percent of families were expelled under Title 42, a smaller proportion than in recent months.

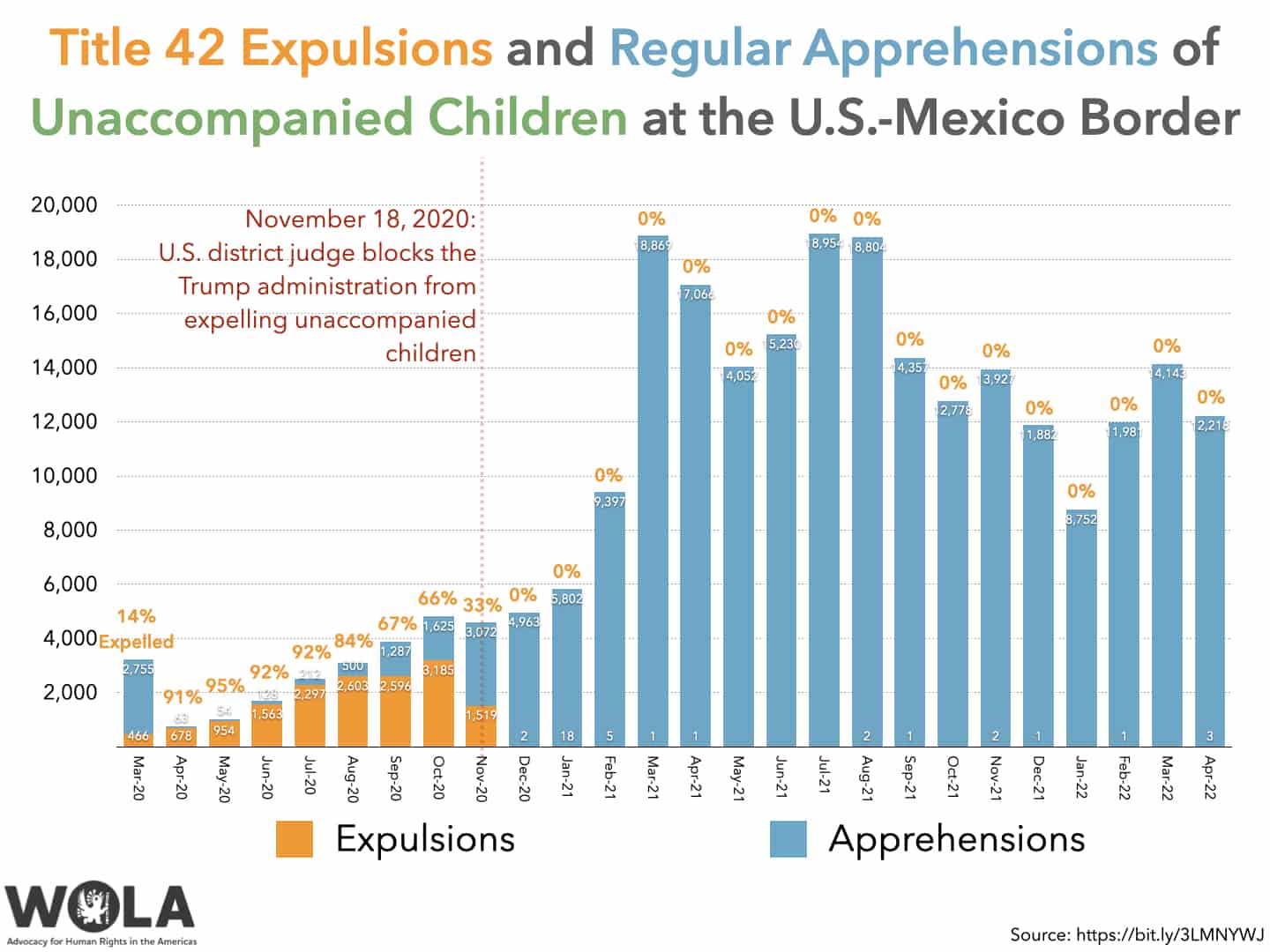

Encounters with children traveling unaccompanied dropped 14 percent from March to April. The 12,221 encounters with unaccompanied children in April were significantly fewer than a year ago, even though the Biden administration is not using Title 42 to expel non-Mexican unaccompanied children.

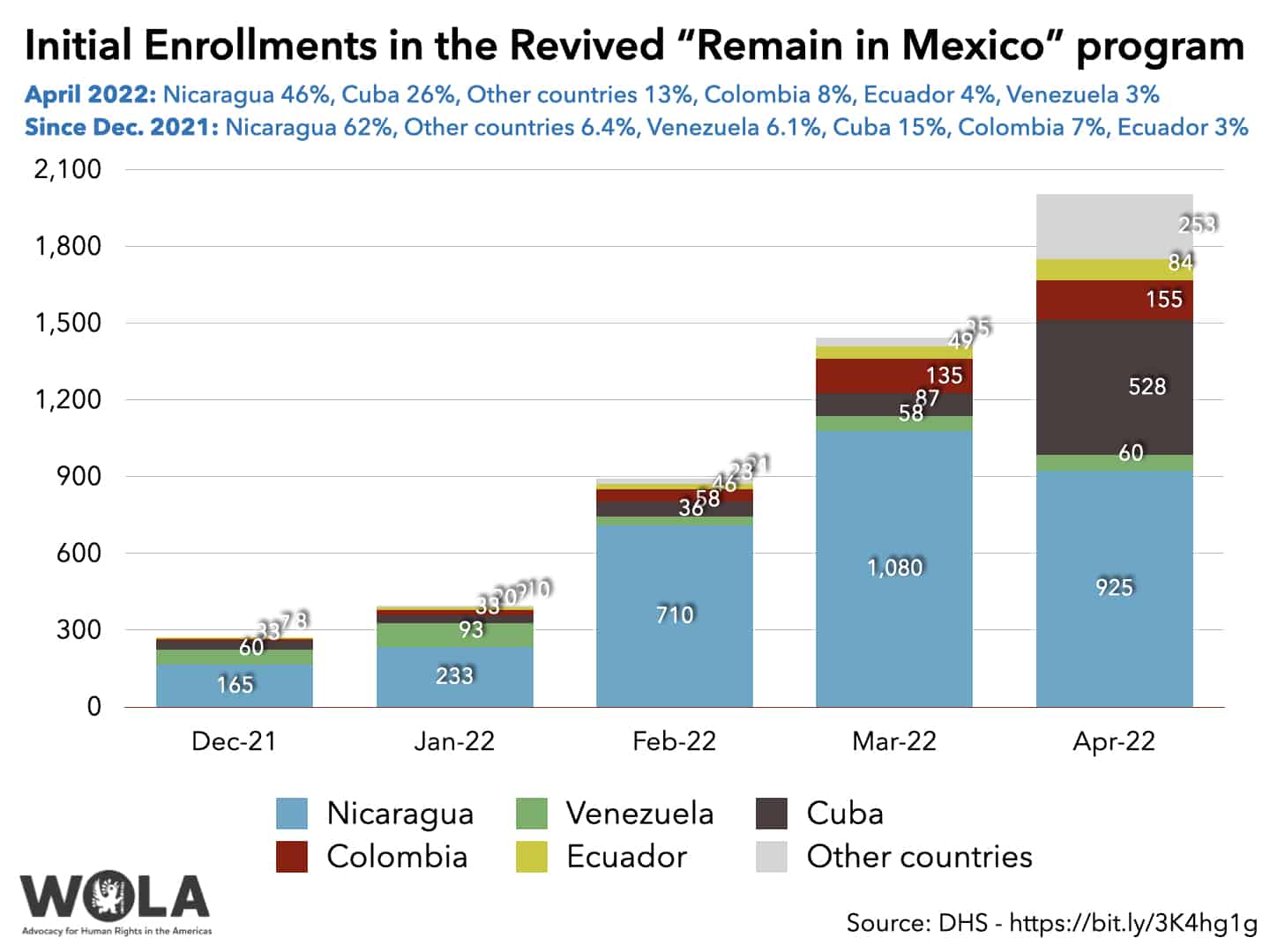

A monthly report from DHS informed that it enrolled 2,005 migrants in April into the “Remain in Mexico” program, revived in December under a Texas federal court order. That is 39 percent more than in March, 124 percent more than in February, and 404 percent more than in January. Of the 5,014 migrants chosen to “remain in Mexico” between December 6, 2021 and April 30, 2022, all have been single adults, 62 percent have been Nicaraguan, 15 percent Cuban, and 7 percent Colombian.

When migrants express fear of being made to remain in Mexico, the Biden administration has taken those claims more seriously than did the Trump administration. 32 percent of those enrolled in the revived program (1,605 of 5,014) have been taken out of it, mostly due to credible claims of fear of harm in Mexican border cities.

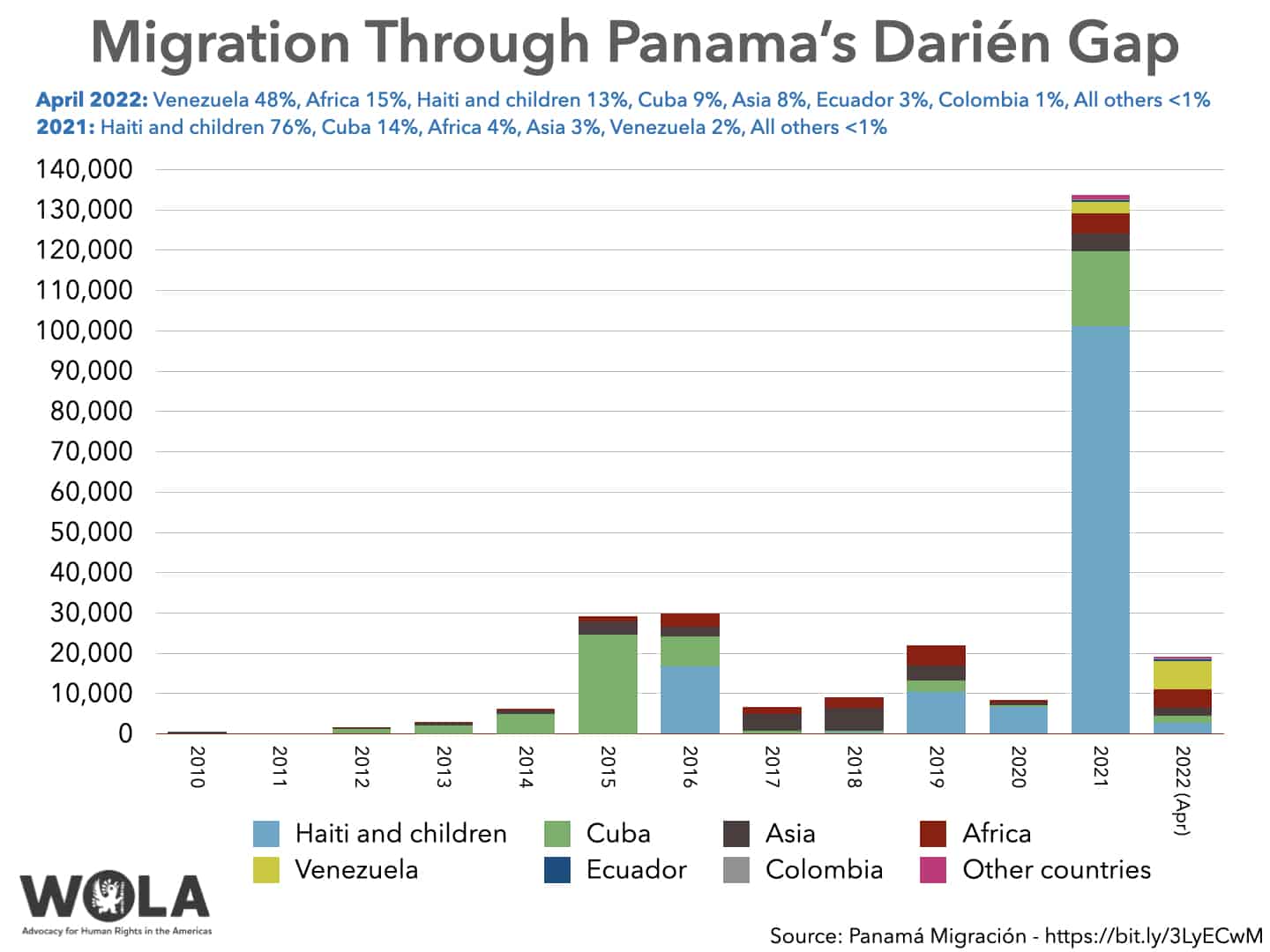

Panama, meanwhile, has posted data through April 30 about migration through the treacherous, ungoverned Darién Gap jungle region near its border with Colombia. In 2021 an unprecedented 133,726 migrants—101,072 of them Haitians traveling from South America—made the difficult 60-mile journey through the Darién. During the first four months of 2022, Panama has registered 19,092 migrants emerging from the Darién—fewer than last year but still on course to be the second largest annual number ever. This year, Venezuelans are the number-one nationality migrating through the Darién.

Doctors without Borders (MSF), one of few humanitarian groups present in the Darién region, tweeted that on May 16 “the Migrant Reception Station (ERM) in San Vicente, Panama, received 746 migrants in a single day,” far more than the daily average of 300. “In a single day, MSF has treated more than 220 patients for issues such as muscle pain, diarrhea, respiratory diseases, among other ailments.” Still more alarmingly, “over the course of this year we have treated 89 patients for sexual violence.”

Migrants who pass through it routinely say that the Darién is the most frightening part of their entire journey. In an article published this week, a Venezuelan migrant passing through Honduras told Expediente Público that he saw two dead bodies while passing through these jungles. Another said that “he and other migrants had been intercepted by armed individuals, who extorted them, sexually abused the women, and kidnapped the daughters of the people traveling with him.”

On April 1, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) determined that the COVID-19 pandemic’s severity no longer warranted maintaining the Title 42 expulsions authority. The CDC set this coming Monday—May 23—as its expiration date. As of May 23, the border will return to the application of normal U.S. immigration law, unless a Louisiana federal court postpones Title 42’s expiration.

“Normal immigration law” means that the right to seek asylum will be restored: migrants who express fear of return to their country will have the credibility of their fear claims evaluated and then have their petitions decided, either by an immigration judge or an asylum officer. It also means that migrants who had sought to avoid apprehension may, if caught, no longer just be quickly expelled: they will face what DHS Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas called “enforcement consequences we bring to bear on individuals who don’t qualify” for protection, like expedited removal, several-year bans on future immigration, and even time in federal prison, especially for repeat crossers. “We do intend to bring criminal prosecutions when the facts so warrant, and we will be increasing the number of criminal prosecutions to meet the challenge,” Mayorkas said during a May 17 visit to the border.

These measures will likely bring an increase in asylum-seeking migrants, and a reduction in other migrants. All, though, will need to be processed in some way—not just expelled at the borderline—which will mean more work for U.S. border personnel.

Whether Title 42 ends on May 23 is up to Louisiana District Court Judge Robert Summerhays, a Trump appointee who is considering a suit brought by several Republican state attorneys-general, including border states Texas and Arizona. Summerhays has already issued a temporary restraining order blocking the Biden administration from starting to phase out Title 42, and he is expected—probably on Friday, May 20—to issue a preliminary injunction keeping Title 42 in place.

We won’t know until Summerhays issues his decision how long Title 42 would remain in place, and under what circumstances. Suzanne Monyak at Roll Call pointed out that his order “could apply nationwide, or only to the border states that sued: Arizona and Texas,” allowing Title 42 to be lifted in California and New Mexico, whose Democratic state governors are not party to the lawsuit.

A judicially ordered suspension of Title 42 would probably reduce momentum in Congress to pass legislation to keep the pandemic order in place. Legislation introduced by Sens. James Lankford (R-Oklahoma) and Kyrsten Sinema (D-Arizona) would keep Title 42 until after the government’s COVID emergency declaration is terminated—potentially suspending the right to seek asylum at the border for years. It has solid support from Republicans and the backing of a few moderate or electorally vulnerable Democrats.

The House of Representatives is adjourning for a two-week Memorial Day recess, and the Senate will take a one-week break on May 27. This means that there is zero possibility of legislative action on Title 42 before at least the week of June 6.

Senate Democrats are weighing a bill to provide supplemental 2022 funding for border security, which Bloomberg Government called “a move that could alleviate concerns within the caucus and defuse a potentially divisive vote attached to a COVID-19 aid package” to prolong Title 42.

Mayorkas and other DHS officials continue to tout their “comprehensive strategy” to ramp up migrant processing and “consequence delivery” should Title 42 end on, or shortly after, May 23. That strategy, laid out in a 20-page late-April document, discusses increasing temporary processing capacity—like tent-based facilities near ports of entry—and personnel surges to manage a post-Title 42 increase in protection-seeking migration at the border. The plan also calls for reimbursements of private charity-run shelters in U.S. border cities, which receive protection-seeking migrants upon their release, provide food and other basic needs, and help with travel arrangements to migrants’ U.S. destinations.

A post-Title 42 increase in asylum seekers is very likely. As reports this week from the New York Times and Fronteras Desk point out, Mexican border cities currently have large populations of migrants waiting for the right to seek asylum to be restored. In the violence-plagued border cities of Reynosa and Matamoros, Mexico, the few existing migrant shelters have seen their capacities far surpassed by an unexpected arrival of thousands of migrants from Haiti, who until recently had rarely arrived at this part of the border, across from south Texas. (DHS is responding to an increase in Haitian migrants with a faster tempo of expulsion and removal flights to Port-au-Prince, which Tom Cartwright of Witness at the Border documents at his Twitter account.)

Many migrants from difficult-to-expel countries are already crossing between ports of entry to ask for protection. In El Paso, Texas at least, this is straining the longstanding network of shelters managed by Annunciation House, whose capacity of about 500 migrants is reduced on weekends when churches are in session. On Sunday May 15, CBP released 119 single adults at the bus station in downtown El Paso, the first such release since late December 2018.

Annunciation House director Rubén García held a press conference on May 18 to warn of the group’s capacity problems and the need for greater cooperation from the local government. Annunciation House received 2,700 migrants the week of May 8, and 1,730 people in just the first three days of the week of May 15. “And it’s only going to continue to increase,” García added. “I have no doubt in fact if Title 42 is lifted on May 23, you are going to see many, many individuals having to be released into the streets.”

The shelter director said he met on May 15 with officials from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), and that 29 FEMA personnel came to Annunciation House’s main shelter on May 17. While this helps, García said, the shelters have been facing a “vast shortage” of volunteers, in large part a result of the pandemic. Another obstacle García identified, according to El Paso Matters, is “the increased vilification of migrants, especially those coming into the United States from the Southwest border. That has turned people away from lending a hand either because of their beliefs or a fear of being targeted for their involvement.”

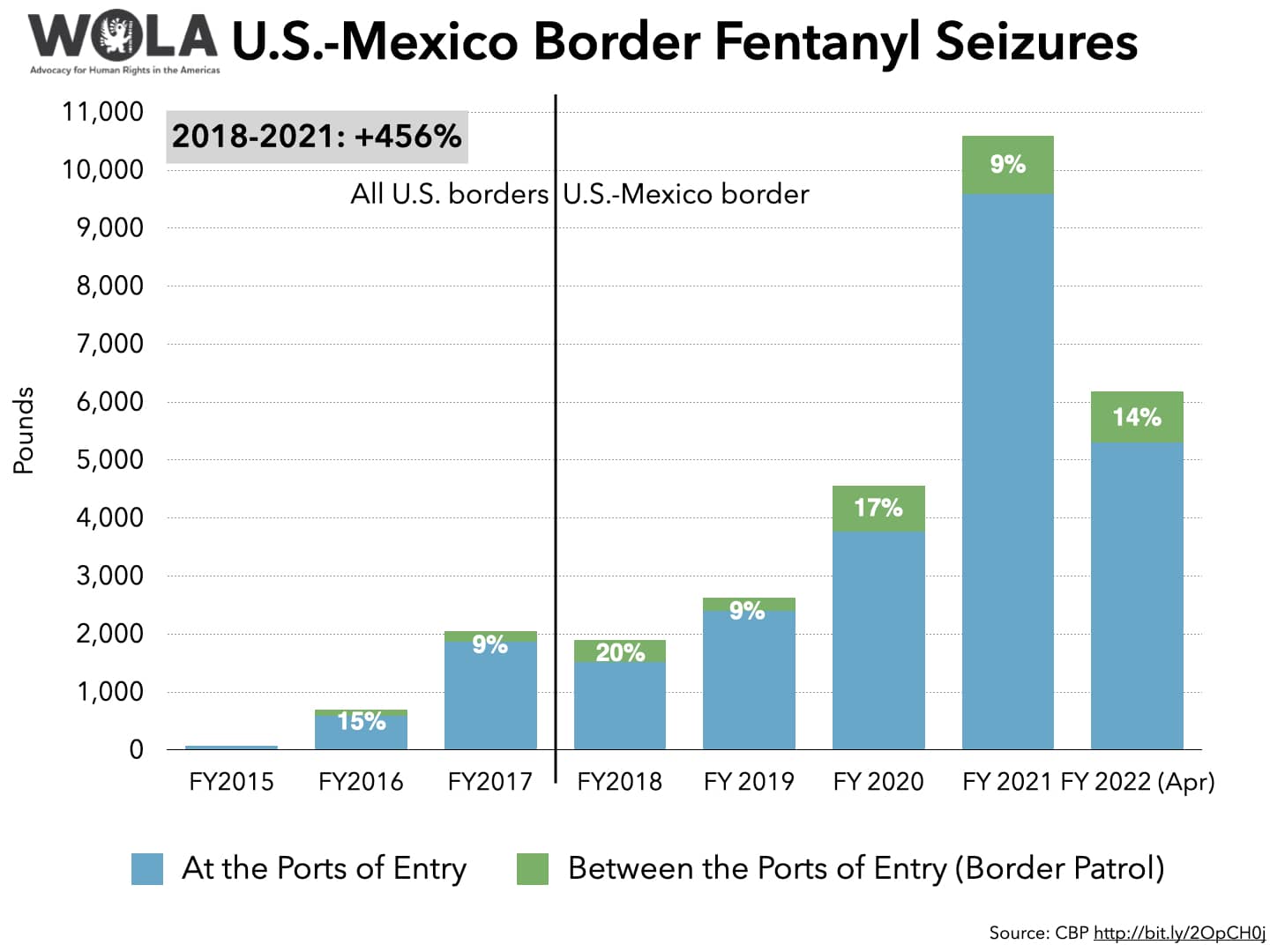

The House of Representatives’ Homeland Security Subcommittee on Border Security, Facilitation, and Operations hosted three DHS officials for a May 18 hearing on the smuggling of fentanyl and other synthetic drugs across the U.S.-Mexico border. As WOLA’s collection of border drug-seizure infographics indicate, fentanyl and methamphetamine continue to cross the border in ever greater amounts, even as seizures of plant-based drugs like heroin, cocaine, and cannabis have remained flat or declined.

“Most illicit drugs, including fentanyl, enter the United States through our Southwest Border POEs [ports of entry],” Pete Flores, the executive assistant commissioner of CBP’s Office of Field Operations, told the subcommittee. “They are brought in by privately owned vehicles, commercial vehicles, and even pedestrians.” 86 percent of fentanyl seized at the border this year has been taken at land ports of entry, while Border Patrol has seized another 6 percent at interior checkpoints, which in nearly all cases means the drugs had recently passed through a port of entry. Only 5 percent of fentanyl seizures take place in the areas between the ports where Border Patrol operates.

“Fentanyl shipments largely originate, and are likely synthesized, in Mexico and are often concealed within larger shipments of other commodities,” Flores explained, adding that CBP calculates that it seized 2.6 billion potential fentanyl doses, and 17 billion potential methamphetamine doses, in 2021.

At ports of entry (including seaports and airports), CBP currently uses 350 large-scale and 4,500 small-scale x-ray and gamma-ray scanners. Right now, CBP has the capacity to scan only 2 percent of “primary passenger vehicles” and 15 percent of “fixed occupant commercial vehicles” crossing the U.S.-Mexico border. Flores said the agency expects to increase these “non-intrusive” scans in 2023 to 40 percent of passenger vehicles and 70 percent of commercial vehicles.

DHS Intelligence official Brian Sulc and ICE Homeland Security Investigations official Steve Cagen coincided in telling the subcommittee that there is little overlap between drug trafficking and undocumented migration. “We’ve seen some instances perhaps of migrants and drugs as a mixed event, but they’re still rare,” Sulc said.

DTOs [drug trafficking organizations] and human smuggling organizations are opportunistic and transactional with their operations, and they’re strongly motivated by profits. So combined drugs and migrant smuggling events are not really a routine practice at all. The illicit actors facilitating these movements are likely to keep these entities separate to minimize the risk of losing the potential revenue from the much higher value drugs, such as fentanyl.

“We see that drugs and human smuggling are separate,” Cagen added. “They might use the same routes, but we predominantly see the drugs coming in through the ports of entry.”