(WOLA)

(WOLA)

WOLA staff visited San Diego, California, and Tijuana, Baja California, during the week of May 2, 2022. We came with a list of research questions about migration trends, security concerns, efforts to hold border law enforcement agencies accountable, and how the region’s service providers were preparing for a likely post-pandemic migration increase. We found:

Looking only at U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) migration data gives an impression that this part of the border is quiet. Of the nine sectors into which Border Patrol divides the U.S.-Mexico border, San Diego—the westernmost 60 miles—is sixth in the number of migrants encountered in April, and so far in fiscal 2022.

In Tijuana, though, the migrant population is large and growing. In the category of “people who have recently arrived from somewhere else” are:

Adding together these sources of migration, we estimate that at least 300,000 people, probably more, have migrated to or through Tijuana in the past year. That is at least 15 percent the size of the city’s population (nearly 2 million), 1 for every 6 or 7 people.

At least 2,000 Haitian citizens, nearly all of whom had been residing in South America, arrived in the city and in nearby Mexicali in December. Many remain on the Mexican side of the border, as the Biden administration has been aggressively using Title 42 to expel Haitians by air. A few thousand citizens of Russia—many of them from the Tatar minority—arrived in late 2021; many sought to reach U.S. soil, which would allow them to seek asylum, by driving rented cars through the official port of entry.

Until the Biden administration launched its “United for Ukraine” initiative on April 25, traveling to Mexico was the quickest way for Ukrainians fleeing the February 24 Russian invasion to reach the United States. Nearly all Ukrainians who took this route—about 20,000 people—entered via Tijuana. In March, the last month for which we have U.S. data, 1 out of every 6 migrants U.S. authorities encountered in San Diego was from Russia or Ukraine (4,020 out of 23,295). Many more came in April.

Since April 25, the land border has again been closed to Ukrainians. Those who remain in Mexico must travel to Mexico City and apply for admission under the United for Ukraine process. We saw no Ukrainian migrants during our time in Tijuana.

The San Ysidro port of entry between Tijuana and San Diego is the busiest land border crossing in the Western Hemisphere. Title 42 has kept San Ysidro closed to people who, though lacking documents, wish to exercise their legal right to present themselves to CBP officers and ask for asylum. Between January 2021 and February 2022, more than 1,000 would-be asylum seekers, including many families, lived under tents and tarps in an encampment at the Chaparral plaza, outside the port of entry.

Chaparral Plaza stands empty.

When we visited, the plaza was cleaned out and fenced off: city authorities, including police and national guardsmen, had cleared Chaparral in a pre-dawn operation on February 6. Authorities say that the encampment’s population had fallen to about 380 people, living in squalid conditions, and that all who wanted shelter were relocated to government and charity-run shelters. Critics of the operation questioned its abruptness and noted a large amount of personal belongings that the encampment’s occupants left behind.

Tijuana has the border’s largest network of migrant shelters: about 37 or 38 now exist in the city. Most are run by churches or religious groups, though there is a large facility run by Mexico’s federal government, a Baja California state-run shelter, and a “filter hotel” for COVID-positive migrants supported by the International Organization for Migration.

Staff at the three shelters we visited say that they are managing for now: all are at high capacity but none was completely full. Any shelter more than several years old was likely founded to accommodate the main migrant population until the mid-2010s: Mexican adult deportees who needed only a few days’ stay. Changes in the migrant population, and U.S. efforts to block access to asylum, have forced shelters to adapt to house families and children, and to accommodate people who need housing for weeks or months.

Shelter personnel, government officials, and advocates we interviewed coincided in pointing out access to health care as the most urgent priority for migrants in Tijuana. Many, including children, are sick and have little chance of seeing doctors or obtaining medicines. Several added that access to information about both countries’ asylum and immigration processes is crucial: rumors continue to outrun the truth. Organizations like ACLU San Diego are partnering with organizations in Tijuana in an effort to manage migrants’ and asylum seekers’ expectations by providing up-to-date information. Some shelters and advocates worried that the Mexican government, at all levels, appears to lack a plan to help manage a possible post-Title 42 increase in migration.

Tijuana has seen an uptick in homicides and other violent crime. Mexico’s federal government has responded by deploying at least 3,000 soldiers and a similar number of national guardsmen to patrol the city. They are very visible in pickup trucks with mounted machine guns. The violence is concentrated in poorer neighborhoods; a main cause is competition for local sales of drugs, especially methamphetamine and increasingly fentanyl.

Though San Diego is U.S. border authorities’ number-one sector for seizures of methamphetamine, fentanyl, heroin, and cocaine, security analysts we consulted agreed that competition for transshipment is probably not causing the increased violence. The more common view was that “micro-trafficking”—competition to sell drugs in the local market—is the stronger explanatory factor. A relative lack of shootouts or killings in the city’s downtown and more prosperous neighborhoods—which were common a decade ago, when cartels were competing for transshipment turf—seems to support that view.

Tijuana is dangerous for migrants. Surveys of migrants at this part of the border conducted by the legal aid group Al Otro Lado, often featured in reporting from Human Rights First, have recorded more than 7,300 migrants’ claims of suffering “rape, sexual assault, kidnapping, human trafficking, armed robbery, and beatings” since the begnning of 2021. Ransom kidnappings occur here, though less frequently than in Mexican border areas across from Texas.

If Title 42 is allowed to expire, many people who have been waiting in Tijuana for a chance to seek asylum may attempt to cross into the United States, whether at a port of entry or somewhere in between. The number of migrants who aim to avoid apprehension—mostly single adults—may decline after Title 42, as DHS officials affirmed that they will once again seek to punish repeat crossers, including through criminal prosecutions, instead of simply expelling them.

Even if overall migration declines post-Title 42, it’s likely that the number of people needing to be processed for asylum will increase. This has spurred concerns, including among many moderate Democratic legislators, of a return to disorder and overcrowding at the border as CBP’s capacities get overwhelmed.

In both San Diego and Tijuana, we heard little concern about possible disorder in processing a larger number of asylum seekers. (This may not reflect views held border-wide. In El Paso, for instance, the city’s largest migrant respite center’s director has voiced concerns about capacity.) Shelters and attorneys believe that capacity exists: space is available near the border, for instance in old California Highway Patrol stations or hotels. They contend that CBP’s true asylum processing capacity was on display during April, when the agency managed as many as 1,000 Ukrainian citizens’ entries each day.

The San Ysidro port of entry.

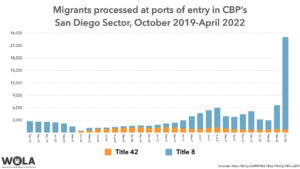

While the humanitarian parole being offered to Ukrainians may have involved less paperwork than asylum, CBP still “tipped its hand,” as one advocate said, by showing that the agency could in fact devote the personnel and resources necessary to transport and register, at the port of entry, a large number of people seeking protection. CBP’s San Diego Field Office adapted, going from processing 2,932 migrants at ports of entry in February, to 6,635 in March, to 23,034 in April.

A Mexican government official told us that while CBP normally has two officers processing asylum at the port of entry, the agency managed to increase that to 24 officers to accommodate the Ukrainians. “We must replicate this for the caravans that come,” said another Mexican official.

Many advocates and shelter personnel, however, viewed the Ukrainian processing as unfair to all other nationalities. Protection-seeking migrants who had been stranded for months or years, most of them from Latin America or Africa, watched a European refugee population walk right past them and get priority access to protection in the United States.

During our visit, CBP had just begun an effort to provide exceptions to Title 42 for the most vulnerable protection-seeking migrants, allowing about 35 per day, chosen with input from local NGOs, to approach the San Ysidro port of entry. A U.S. government court filing noted 1,006 such Title 42 exceptions at 6 ports of entry during the week of May 3-9, including 487—nearly 70 per day—at San Ysidro.

WOLA’s new Border Oversight database has tracked over 230 allegations of abuse or misconduct by U.S. border law enforcement agencies border-wide since 2020, including 30 in Border Patrol’s San Diego sector or CBP’s San Diego field office.

While we were visiting, CBP announced a notable step forward for accountability. A May 3, 2022 memorandum from CBP Commissioner Chris Magnus terminated Border Patrol’s Critical Incident Teams (CITs), secretive units that often arrive at the scene when agents may have misused force or otherwise violated human rights. CITs stood accused of altering crime scenes, interfering with law enforcement investigations, and coming up with exculpatory evidence to protect agents.

This result owes to the work of the Southern Border Communities Coalition (SBCC), a non-governmental coalition of 60 border organizations that revealed the extent of the CITs in October and has led efforts to abolish them. SBCC staff based in San Diego took on the CITs when they learned of the teams’ interference with the investigation of a high-profile case in San Diego, the 2010 beating death of migrant Anastasio Hernández outside the San Ysidro port of entry.

Advocates we spoke with underscored, though, that important human rights concerns about CBP and Border Patrol persist along this part of the border. Two fatal shootings, in 2020 and 2021, remain under investigation to the best of our knowledge. Human rights defenders cited frequent vehicle pursuits, including an April 23 incident in El Cajon, California, that led to the death of a Native American driver. Some mentioned concerns about misuse of newly deployed surveillance technologies, including facial recognition capabilities and mobile phone scanners, which might listen in on nearby non-suspect U.S. citizens’ conversations without probable cause. An attorney in Tijuana said that CBP officers at the port of entry frequently mislead asylum seekers, telling them things like “there’s no asylum,” or “go to the west entrance [which is closed] to put your name on the list.”

Also of immediate concern is a sharp rise in deaths and injuries from migrants attempting to climb over the border fence, 30 feet high in some places, rebuilt during the Trump administration. An April 29 article in the Journal of the American Medical Association, featured in recent Washington Post and Guardian coverage, found that since 2019, the number of patients arriving at the U.C. San Diego Medical Center’s trauma ward after falling off the wall had quintupled, to 375, and 16 people had died of their falls, up from zero in 2019. “At Scripps Mercy Hospital, the other major trauma center for the San Diego area,” the Post reported, “border wall fall victims accounted for 16 percent of the 230 patients treated last month, a higher share than gunshot and stabbing cases.”

Double-layer fencing seen from Tijuana.

Because there is a double layer of fencing between most of San Diego and Tijuana, many wall-climbers here are probably not attempting two climbs: they are asylum seekers trying to turn themselves in to U.S. authorities while on the patch of U.S. soil between the two rows of wall. Those who die or are maimed in the attempt should not have had to do this: if they wanted asylum, they should have been able to ask for it at the port of entry, as U.S. law specifies.

They, too, are victims of the Title 42 policy, which is supposed to be a public health measure, not a tool to reduce the number of asylum seekers coming to the border. The rapid, orderly processing of 20,000 Ukrainian citizens in a few weeks, in San Diego in March and April, gave us a glimpse of the more orderly asylum process that the U.S. government continues to be slow and reluctant to build. What we saw in Tijuana, a city of 2 million accommodating more than 300,000 migrants per year, made clear that in this era of heightened worldwide migration, throwing up barriers just creates a host of new problems. The solution lies in dramatically increased capacity for orderly processing of protection claims, humane alternatives to detention, and adjudication with due process.