With this series of weekly updates, WOLA seeks to cover the most important developments at the U.S.-Mexico border. See past weekly updates here.

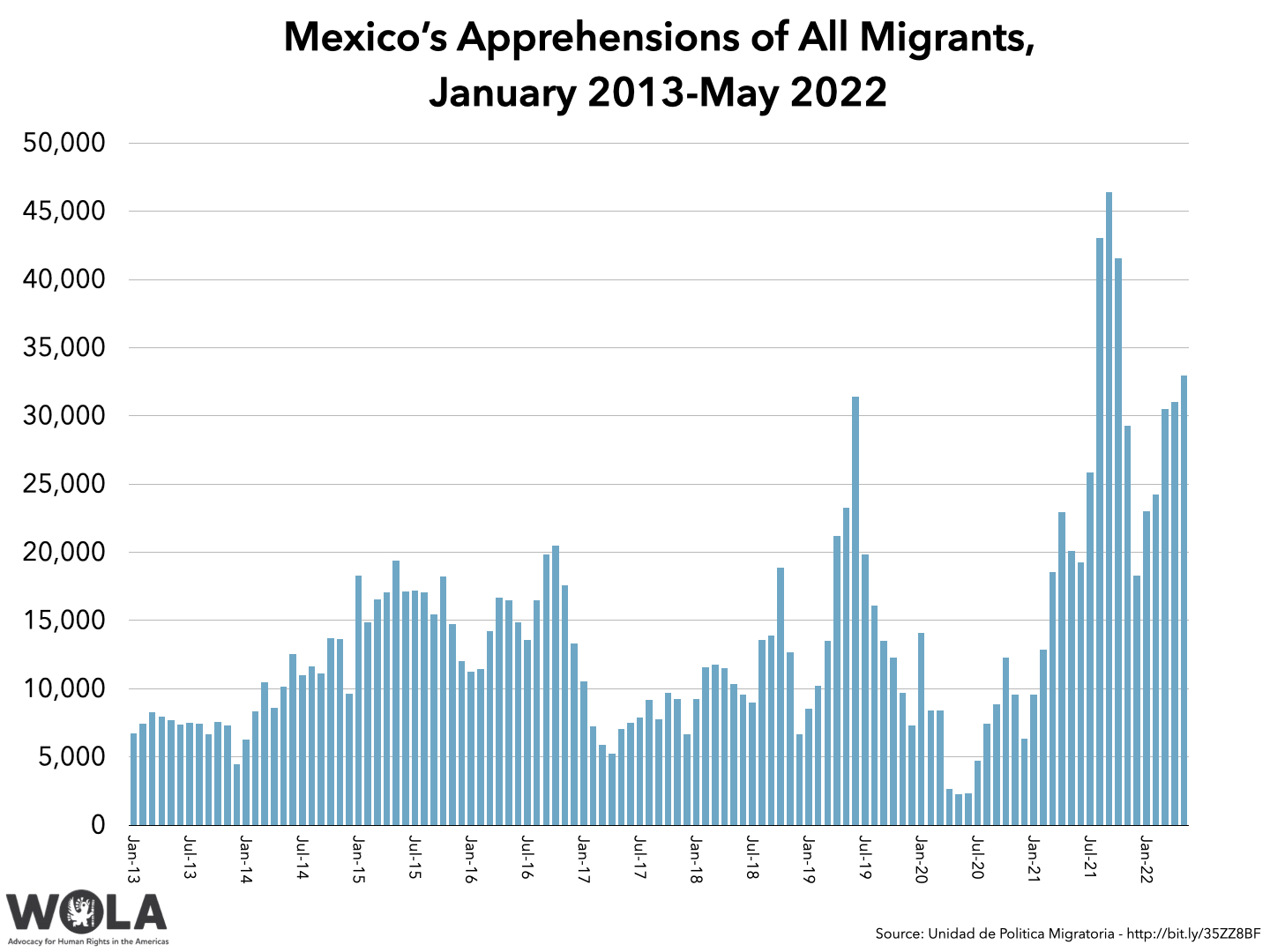

In late June Mexico’s Interior Department (Secretaría de Gobernación), through its Migratory Statistics Unit, released data about migration through the country during May 2022. That month, Mexican authorities apprehended 32,948 migrants, their 4th-largest monthly total on record.

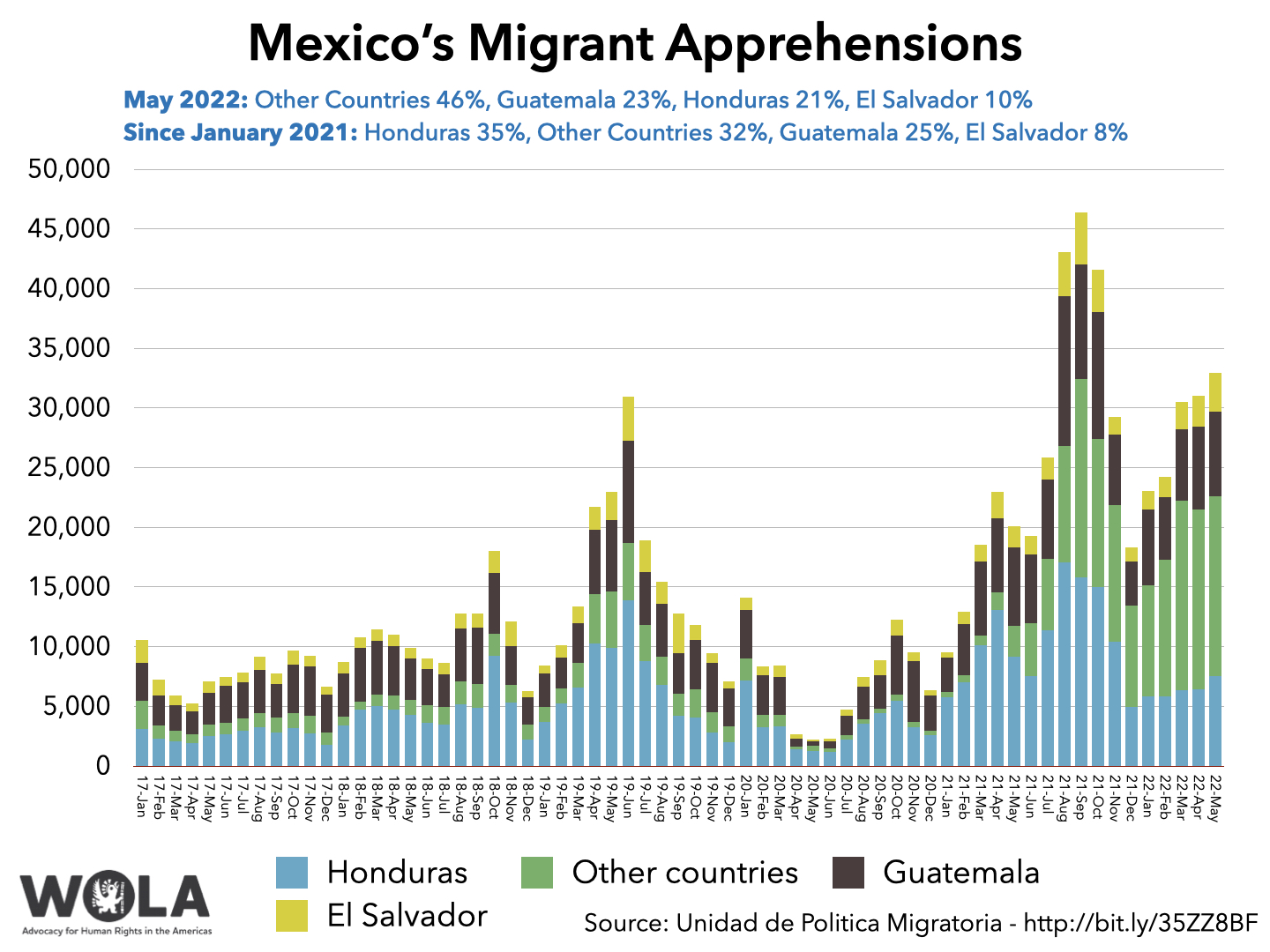

Of that total, only 54 percent came from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras, the countries of Central America’s so-called “Northern Triangle.” Until the middle of last year, these three countries very rarely made up less than 80 percent of Mexico’s migrant apprehensions.

The remainder—shown in green in the above chart—come from the rest of the world, mainly the Americas. The following 13 nationalities measured at least 100 apprehended migrants in Mexico in May:

The number of apprehended migrants from Haiti (#12) has fallen sharply: fewer than those from Russia in May. Haitian migration through Mexico reached a peak in September 2021, the month of the infamous Border Patrol “whipping” or “flailing reins” incident in Del Rio, Texas. That month, Mexican migration and security forces apprehended 9,009 Haitian citizens.

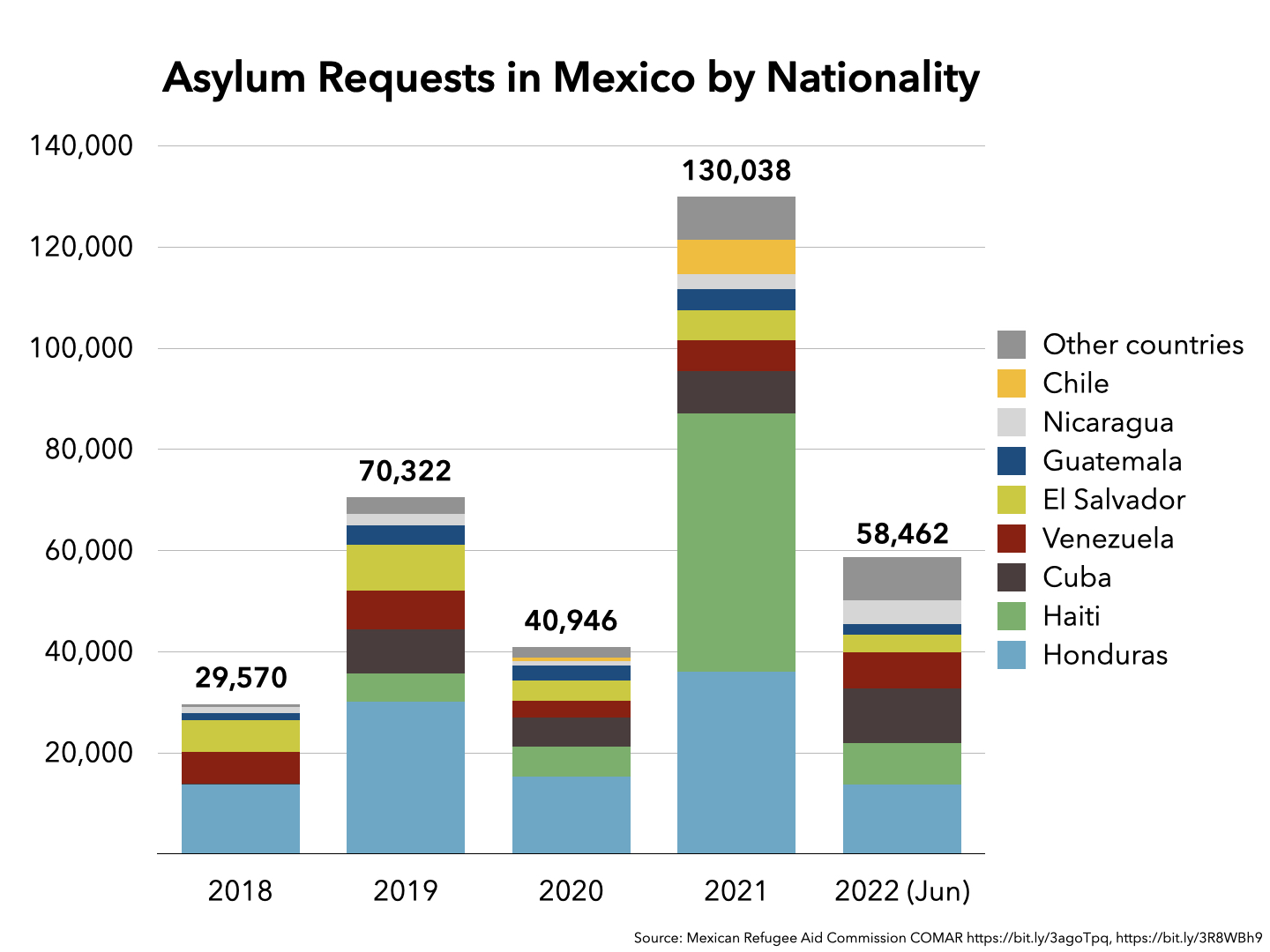

In early July, Mexico’s refugee agency (COMAR) reported that 9,740 people requested asylum in Mexico in June. That is slightly fewer than in February, March, and April, but still puts COMAR on track for its second-busiest year ever, with 58,462 applications during the first half of the year.

In 2021, a large number of Haitian citizens, migrating north after spending years living mostly in Brazil and Chile, made Haiti the number-one country of origin for asylum seekers in Mexico. The Chileans who appear in the above chart in 2020 and 2021 (in orange) were almost entirely the Chilean-born children of Haitian migrants.

This year, Honduras has returned to the number-one position that it held during most recent years. Arrivals from Cuba, Venezuela, and Nicaragua all appear likely to break past records.

Mexico has received 7,196 asylum applications from Venezuelan citizens during the first half of 2022, more than in all of 2021 (6,134). That is mainly because in January, at strong U.S. government suggestion, Mexico began requiring visas of visiting Venezuelans, which made it difficult for them to arrive by air and travel to the U.S. border with valid documentation.

A July 5 update from Human Rights Watch (HRW), based on field research near Panama’s Darién Gap jungle region, blames new visa requirements for a jump in transit through this treacherous, roadless zone.

Since January 2022, Mexico, Costa Rica, Honduras, and Belize have imposed new visa requirements on people from countries whose citizens have been arriving at the US southern border in greater numbers, including Venezuelans. Many Venezuelans say they are traveling through the Darien Gap because these visa requirements have limited their ability to take safer routes to seek protection in the United States.

HRW notes that “In some cases, governments have reportedly imposed these new immigration restrictions in response to pressure from the United States.”

Most citizens of Venezuela and other countries who take the land route end up in Mexico’s economically depressed southern border-zone city of Tapachula, Chiapas. There, as WOLA documented in an early June report, Mexico’s government usually forces them to remain while awaiting results from its backlogged asylum system.

Migrants have taken to organizing mass protests, which take the form of short-lived “caravans” along the highway leading out of Tapachula, in an effort to press Mexico’s government to allow them to leave the city. The latest, involving at least 2,000 mostly Venezuelan migrants, departed Tapachula on July 1. It was at least the third such protest in the past month and the ninth so far this year.

As has been occurring more frequently over the past month, Mexican authorities dispersed the latest protest by July 3, offering the migrants Multiple Migratory Forms (FMMs, basically tourist cards) allowing them to be in the country for 30 days.

With an FMM, migrants have a documented status allowing them to board buses and travel through Mexico, including to the U.S. border zone. As noted in WOLA’s June 17 and June 24 updates, citizens of Venezuela and other countries, holding FMMs obtained in the Tapachula area, have begun arriving in Mexico’s northern border states.

Some of these states’ governments have sought to limit their access to the U.S. border by prohibiting sales of bus tickets. Hundreds of mostly Venezuelan migrants walked about 240 miles from Monterrey, where they were stranded at the bus station, to the border city of Piedras Negras. The Mexican daily Milenio reported that they have made it to the United States.

The distribution of FMMs can be seen as a “least bad” option for those migrants who are in transit through Mexico, at least until they have expanded access to legal pathways and asylum from along the migratory route. Providing a temporary legal status takes business away from migrant smugglers and corrupt officials who would extort migrants.

However, as with Mexico’s use of other tools such as “exit visas” (oficios de salida) in the past, as well as humanitarian visas, this measure could lead to diplomatic issues with the U.S. government, which has made clear that it expects Mexico to limit the flow of undocumented migration toward the U.S. border. (The above-cited apprehension data, of course, indicate that Mexico continues to block near-record numbers of migrants.)

Also noteworthy in Mexico’s May data release is information about U.S. deportations of Mexicans into Mexico, as recorded by the Migratory Statistics Unit. (These are deportations, not Title 42 expulsions, which often occur without a Mexican official on hand to record them.) In recent months, deportations of Mexicans have reached higher levels than during the Trump administration, in part due to a larger number of Mexican citizens now attempting to migrate into the United States.

Notable is the recent growth of this chart’s yellow segment: deportations into Tamaulipas, the only Mexican border state considered so violent and dangerous that the U.S. State Department has given it a Level 4 “Do Not Travel” warning.

Since WOLA published its July 1 update, media reports have added grim new details to our understanding of what happened in San Antonio on June 27, when 53 migrants died of heat-related causes in the container of a cargo truck taking them from the border city of Laredo.

The truck’s driver, 45-year-old U.S. citizen Homero Zamorano, did not know that the container’s air conditioning unit had stopped working, according to federal court charges filed against Zamorano’s co-conspirator, 28-year-old U.S. citizen Christian Martínez.

The federal complaint reports that Martínez repeatedly texted Zamorano throughout the afternoon of the 27th, receiving no replies. When the driver was arrested, hiding in brush near the trailer parked on a side road on San Antonio’s outskirts, “he was high on methamphetamines,” according to two officials cited by the Washington Post.

Martínez’s unanswered text messages, as well as those of a Guatemalan woman who communicated with her father until the smugglers confiscated the migrants’ phones, indicate that the truck likely departed Laredo during the 12:00 hour of the 27th. The truck would be discovered about five hours later in San Antonio, about three hours’ drive away, its cargo container’s door ajar but most of the migrants inside either deceased or too weak to move.

The Guatemalan woman, 20-year-old survivor Yenifer Yulisa Cardona Tomás, said that the truck’s destination that day was Houston, another three hours from San Antonio. Smugglers, she said, “covered the trailer’s floor with what she believes was powdered chicken bouillon, apparently to throw off any dogs they might encounter at checkpoints.” The truck made a few stops along the way to San Antonio, picking up more migrants.

Media reports profiled some of the 53 deceased and 14 surviving migrants aboard the truck, all of whom appear to have come from Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. The two youngest were thirteen years old.

“Human smuggling by tractor-trailer has increased exponentially in the past decade,” Craig Larrabee, an investigator with Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s Homeland Security Investigations division (ICE-HSI) told Reuters. Zamorano and his accomplices’ truck had its identifying information “cloned” to look like a vehicle that would commonly pass through Border Patrol’s interior vehicle checkpoints along Interstate Highway 35, as it easily did, in Encinal and Cotulla, Texas. “The truck was waved through because the traffic was backing up,” Rep. Henry Cuellar (D-Texas), who represents Laredo in the House of Representatives, told the Washington Post, noting that Border Patrol is strained by recent increases in migration.

What will become of the tragedy’s 14 survivors remains unclear. A letter from 103 non-governmental organizations, including WOLA, observes, “In previous mass casualty incidents, victims and witnesses have ended up detained and deported within hours after being released from the hospital.” The letter cites the deportation of a survivor, “while still wearing clothes streaked with blood,” three days after an August 2021 car crash in Texas that killed 10 people.

The letter calls on the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to parole survivors into the United States and assist them “in applying for a U or T visa or asylum.” The visa categories refer to victims of human trafficking or other serious crimes who have information potentially useful to law enforcement. It remains unknown for whom the truck driver Zamorano, co-conspirator Martínez, and two other arrested men were working.

Battles between organized crime groups in Tamaulipas, Mexico, across from south Texas, have drawn the most attention, but the security situation remains difficult in many communities across the border from the United States. Two incidents this week highlighted serious challenges in the western part of the border zone.

The desert town of Altar, Sonora, has long been known as a staging area for migrants about to make the dangerous journey into the U.S. state of Arizona, about 60 miles to the north. Relatedly, it has also been known for the strong influence of violent organized crime.

On July 2, Altar erupted in violence. Mexican soldiers arrested three organized crime figures, one of them reportedly a relative of José Bibiano Cabrera, alias “el Durango,” a leader of the Gente Nueva, an elite armed group linked to Los Chapitos, the faction of the Sinaloa cartel headed by sons of imprisoned boss Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán.

At a press conference on July 3, Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador described what happened:

Yesterday, in Sonora, they arrested three famous criminals, a group of soldiers, and they had them subdued, detained, and 10 to 15 pickup trucks arrived. It was 60 against 10. The person in charge of the operation, with much aplomb asked for support because they were offering him a deal: if they released the leaders of the gang nothing would happen to them, they were offering the group of soldiers 10 million pesos [US$500,000]. And the reinforcements arrived and there was a confrontation, an army officer lost his life, but the leaders were arrested.

Armed men blocked the roads leading in and out of the desert town. “Videos posted by Altar residents on social media showed a raging gunbattle, apparently including the sounds of automatic weapon fire,” the Associated Press reported.

July 2 was also an unusually violent day further west, in Baja California south of San Diego. Six people were massacred in the Pacific coast town of Ensenada, and another was killed in the beachfront town of Rosarito, closer to Tijuana. In Tijuana, where the homicide rate leads Mexico’s major cities, the daily El Imparcial reported that “a police officer from the intelligence area, accompanied by a member of the Army, was shot at. The municipal officer was seriously wounded in the head, while the military officer repelled the attack,” and the assailants fled in the police vehicle.

“There is the potential for confrontations between criminal organizations and Mexican security forces in Tijuana and Rosarito, Baja California, following the July 2 arrest of a prominent cartel leader,” reads a July 4 Level 3 travel warning, covering northwestern Baja California, from the U.S. Embassy in Mexico City.