With this series of weekly updates, WOLA seeks to cover the most important developments at the U.S.-Mexico border. See past weekly updates here.

Reuters reported on September 14 that the Biden administration is “quietly pressing” Mexico to allow U.S. border authorities to expel more asylum-seeking migrants from Cuba, Nicaragua, and Venezuela under the Title 42 pandemic authority.

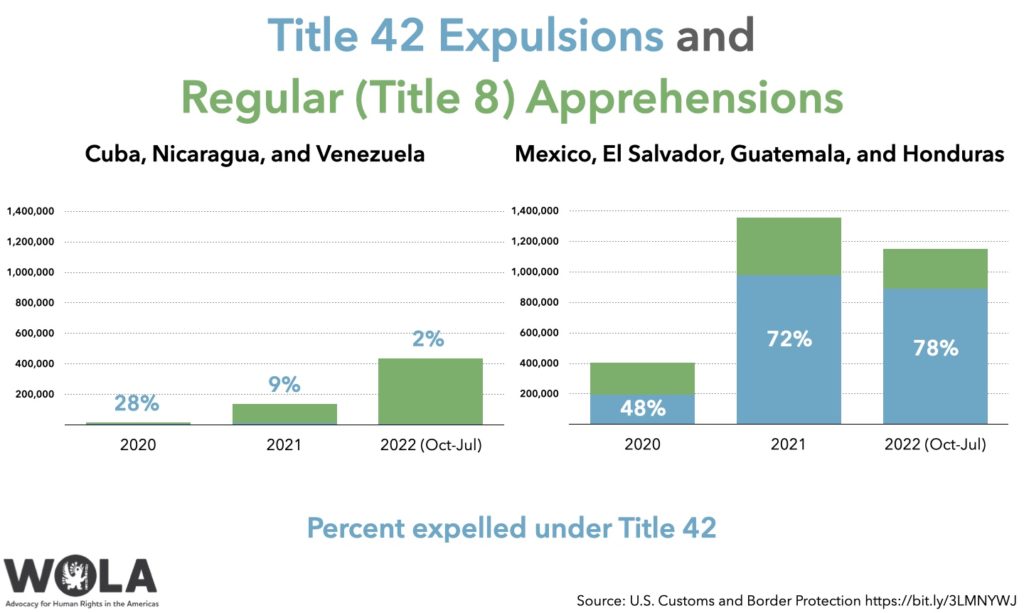

When the Trump administration developed this policy in March 2020—which denies the right to request asylum in the name of public health—Mexico’s government agreed to take back expulsions of its own citizens, and those of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. Since then, U.S. authorities have expelled citizens of those four countries across the land border into Mexico more than 2 million times.

Citizens of most other countries, whose expulsions would happen by air at some cost, usually avoid Title 42 expulsion and, as a result, may request asylum, which often involves release into the United States pending immigration hearings.

With the pandemic easing, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) had set May 23, 2022 as Title 42’s final date, with a return to normal immigration processing and a restoration of the right to ask for asylum. Litigation by Republican state attorneys-general led to a Louisiana federal district court overturning the CDC decision in mid-May, forcing the Biden administration to continue implementing Title 42. The administration continues to oppose that judge’s order in the federal courts, seeking to win back the right to end the pandemic authority.

In early May 2022, when Title 42’s end appeared imminent, administration officials convinced Mexico to take back a limited number of Cuban and Nicaraguan asylum seekers. Expulsions of those countries’ citizens jumped from 639 in April to 4,172 in May. Mexico, though, had only agreed to accept these expulsions until May 23, and the number of expulsions declined to 605 in June.

Arrivals of migrants from Cuba, Nicaragua, and Venezuela have more than quadrupled since 2021, from 94,000 during the first 10 months of fiscal year 2021 (October 2020-July 2021) to 438,000 during the same period this fiscal year. U.S. authorities have used Title 42 to expel 2 percent of them.

Encounters with migrants from Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras are near their highest level in over 15 years, but have declined from 2021 (154,000 in July 2021, 104,000 in July 2022). U.S. authorities have used Title 42 to expel 78 percent of them.

Now, even as it opposes the court order preventing it from ending Title 42, the Biden administration is asking Mexico to expand it, this time allowing expulsions of Cubans, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans, according to “seven U.S. and three Mexican officials” whom Reuters cited.

“Behind closed doors, some Biden officials still view expanding expulsions as a way to deter crossers, one of the U.S. officials said, even if it contradicts the Democratic Party’s more welcoming message toward migrants,” Reuters noted. The article offered a previously unreported detail: that the White House is asking Panama to accept some expelled Venezuelans who passed through the country en route to the United States.

Of the 128,556 migrants from Venezuela whom U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) encountered between October and July, 59 percent crossed into the United States in Border Patrol’s Del Rio sector, a rural region of mid-Texas whose largest border cities are Del Rio and Eagle Pass. Now, Venezuelan migration—which has been increasing since March—appears to be shifting westward.

“For weeks, El Paso has been teetering with a rising number of migrants, as smugglers shift from Eagle Pass and Del Rio to West Texas,” Alfredo Corchado reported in the September 9 Dallas Morning News. It is possible (though unconfirmable) that migrant smuggling routes may have shifted upstream from the Del Rio sector because of a large number of recent drownings in the Rio Grande in that region, including a mass tragedy in Eagle Pass on September 1.

Before September began, Border Patrol agents in the El Paso sector—which includes Texas’s two westernmost counties and all of New Mexico—were encountering about 900 migrants per day. Of Border Patrol’s nine U.S.-Mexico border sectors, El Paso has been in fourth place for migrant encounters so far in fiscal 2022, but had edged up into third place more recently.

Since about the week of September 4, Border Patrol’s daily average in El Paso has risen to 1,300 or 1,400 per day. “Among those migrants arriving over the past five days are an average of 660 Venezuelans per day,” a Border Patrol spokesperson told the El Paso Times on September 14.

Asylum seekers have been arriving in Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, the city that shares the border with El Paso, and wading across a Rio Grande that, at current low water levels, is roughly ten yards wide. They have been arriving in groups of as many as 300 at a time. There is a border fence on the U.S. side of the river, perhaps 100 yards from the ever-shifting riverbank.

“Faced with the massive arrival of migrants at the border, elements of [Mexico’s] National Guard and INM [Mexico’s immigration agency, the National Migration Institute] went this Monday, September 12, to the section of the Rio Grande where the migrants were entering the United States, but they were only observing the process,” reported El Paso Matters and the Ciudad Juárez daily La Verdad at the Venezuelan outlet Tal Cual.

Asylum seekers wait in the space between the river and the fence to turn themselves in to Border Patrol agents, who take them to El Paso’s Border Patrol processing center. If the migrants are from countries to which Title 42 expulsion is difficult—like Venezuela, whose current government the Biden administration does not recognize—then most are given notices to appear before asylum officers or immigration judges and released into El Paso.

Releases of asylum seekers are nothing new for El Paso. City officials say that less than 1 percent of migrants released in El Paso intend to stay there. As the rest have destinations elsewhere in the United States while they await their court dates, the city’s most pressing need is short-term shelter for the released migrants. Its network of short-term shelters, principally Annunciation House which has 14 facilities in the area, can assist about 800 migrants each day.

That is significantly less than the 1,300-1,400 currently arriving (not all of whom get released into El Paso: some adults are detained, and other nationalities may be expelled or deported). The Border Patrol processing center, where migrants should not be held for more than 72 hours except during emergencies, is currently holding about 3,500 people—more than 3 times its capacity.

When shelters are full and Border Patrol still needs to “de-compress” its processing center, the agency releases migrants onto the city’s streets, usually in the vicinity of the Greyhound bus station. As of the morning of September 14, that had happened to about 900 migrants over the prior week, the El Paso Times reported.

The city has paid for some hotel rooms, but other migrants are sleeping in tents near the bus station. (“When you’ve waded through jungles and mountains, walked in waist-deep mud and crossed rivers that nearly drowned you, this is nothing,” Miguel Ángel, a 24-year-old Venezuelan man, told El Paso Matters outside his tent.) El Paso expects to bill the federal government for reimbursement for lodging and transportation costs.

Unlike most prior populations of asylum seekers, a large portion of the arriving Venezuelans do not have relatives, contacts, or support networks in the United States. They lack a plan and a particular destination in the U.S. interior. Normally, a shelter like Annunciation House puts migrants in touch with U.S.-based contacts who help them pay for transportation to their destination within the United States. Many Venezuelans, though, lack these contacts, destinations, and money for bus or plane fare.

“A very high percentage of them don’t have a sponsor and they have no place to go, and so that backs everything up,” Annunciation House Director Rubén García told the Dallas Morning News. “They did not have a network set up in America like the other migrants do. That’s what threw this into a tailspin,” El Paso City Manager Tommy Gonzalez told Border Report.

Many Venezuelans point to New York as a destination. Since August 23, El Paso’s city government has so far paid for about 25 charter buses to send more than 1,135 recently arrived migrants to New York. The city plans to spend about $2 million on bus transportation over the next 16 months.

In an effort to send a political message to Democratic-run cities, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott (R) has been sending busloads of asylum-seeking migrants to Washington D.C., New York, and now Chicago since April. Those buses mostly depart from Del Rio, not El Paso. A September 8 Houston Chronicle investigation found that Abbott’s busing scheme has been costing Texas taxpayers $1,700 per migrant. This is part of a larger set of hardline border-security activities for which Abbott has now spent over $4 billion, cobbling together the funds with some creative accounting, including the use of federal COVID-19 relief funds, the September 13 Dallas Morning News reported.

Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey (R) has joined Texas in sending busloads of migrants to northeastern cities. On the afternoon of September 14, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis (R) added a new stunt, paying to fly 50 Venezuelan and Colombian asylum seekers to Martha’s Vineyard, a resort island in Massachusetts, apparently under false pretenses.

More than 6.1 million of Venezuela’s roughly 30 million people have left the country since the mid-2010s. Most migrated to other Latin American countries: as recently as February 2021, U.S. border authorities had not encountered more than 1,000 Venezuelan citizens per month. Venezuelan arrivals at the border began increasing in mid-2021, reaching nearly 25,000 in December.

Until January 2022, most Venezuelan migrants arriving at the U.S.-Mexico border flew to Mexico, which had not required visas of visiting Venezuelans. Under strong U.S. urging, Mexico (along with Costa Rica and Belize) began requiring visas of Venezuelans on January 22 of this year.

Encounters with Venezuelan migrants dropped to 3,073 in February 2022, but quickly recovered (to 17,650 in July) as a growing number of Venezuelan citizens opted to migrate by land.

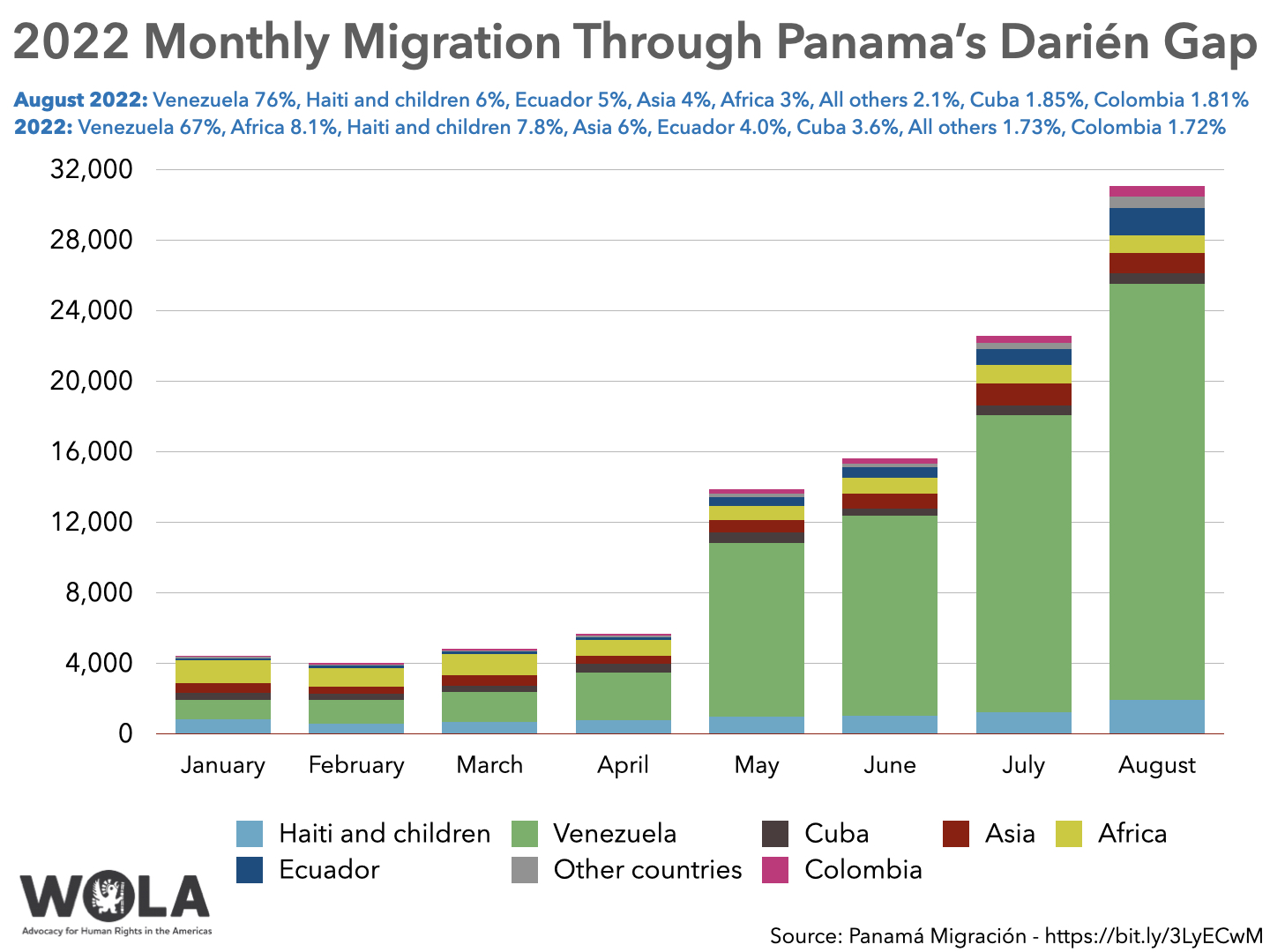

This 3,000-mile journey requires passage through the Darién Gap, a jungle region along the Colombia-Panama border where the Pan-American Highway was never built. Migrants walk about 60 miles through dense jungle with venomous animals, treacherous rivers, and almost no state presence, often falling prey to bandits, rapists, drug traffickers, and unscrupulous migrant smugglers. At its aid post near the end of the Darién route, Doctors Without Borders reported attending to 100 sexual violence victims in just the first five months of 2022.

In the first four months of 2021, Panama’s migration authorities registered just 15 Venezuelan citizens passing through the Darién Gap. By January 2022, that number had increased to just over 1,100. Since then, with the visa-free air route to Mexico closed off, the number of Venezuelans making the Darién journey has exploded, reaching 23,632 in August. During the first 8 months of 2022, 68,575 Venezuelans have passed through the Darién Gap.

(Venezuela is green on this chart.)

(Venezuela is green on this chart.)

Panama’s border police (Servicio Nacional de Fronteras de Panamá, Senafront) revealed this week that it had found the remains of 18 migrants in the Darién during the first 8 months of 2022. Five drowned, and the other thirteen died of unknown causes. The actual death toll is doubtlessly higher, given migrants’ frequent accounts of seeing bodies on the journey, and given Panamanian authorities’ scarce presence along the full length of the route.

“You step on bodies, even children’s bodies. That jungle smells like death from the moment you enter until you leave,” two Venezuelan migrants in San José, Costa Rica told a reporter from Venezuela’s Efecto Cocuyo, which has been reporting extensively along the migrant trail.

In another story, Efecto Cocuyo describes “the grandfather’s camp” (“el campamento del abuelo”), a gathering of tents a few days’ journey along the Darién trail. (“Who is the grandfather? Nobody knows, nobody has seen him.”)

For the Monterrey family [Venezuelan migrants who passed through the Darién], this camp was one of the worst places in the jungle. The site is improvised, with wooden poles everywhere and some spaces covered with zinc or tarpaulin. “That place is terrible, you see animals mixed with garbage and even decomposing humans,” said Juan Monterrey.

In still another story, an Efecto Cocuyo reporter tells of his own migration through the Darién Gap in 2019:

In the days I was there I was threatened with death and harassed by human traffickers and armed groups that dominate specific parts of the route. I was kidnapped for 19 hours during which I felt that my life no longer belonged to me. I saw the corpse of a stranger in the jungle and also sick, lost and disoriented people who had been abandoned to their fate. By the time I finished the tour, I had been stripped of practically all my belongings.

The inhospitable jungle, located on the border between Colombia and Panama, is like a sort of Tower of Babel where people from more than 50 countries and different languages converge.

(See also Canadian journalist Nadja Drost’s April 2020 account of the Darién journey in California Sunday, which won her a Pulitzer Prize.)

Many of the Venezuelan migrants along this route have only recently left their country. Many others, though, abandoned Venezuela months or years ago and have had little success elsewhere in South America where employment is scarce, visa regimes are tightening, and discrimination is common.

The Ecuadorian daily El Universo reported on September 13 from Tulcán, Ecuador’s border city where the Pan-American Highway crosses into Colombia. There, its reporters note, the past three months have seen an increase in northward migration of Venezuelans leaving Argentina, Chile, Peru, and elsewhere in South America. “But in recent weeks, the presence of Venezuelans at the border terminals of Huaquillas and Tulcán has tripled to between 500 and 700 travelers per day.” The Tulcán bus terminal’s administrator estimated that perhaps 60 percent of the Venezuelans, especially the younger ones, intend to migrate to the United States, while the rest may be giving up and returning to Venezuela.

Efecto Cocuyo meanwhile reported from an area near the bus terminal in San José, Costa Rica, where Venezuelan migrants congregate, some sleeping in tents, just days after emerging from the Darién. What keeps many from moving immediately on to Nicaragua and further north is knowledge that Nicaraguan authorities charge $150 per migrant for “safe conduct” to pass through the country’s territory. “For many, the Darién took everything from them, so they have to stay in Costa Rica to collect the money or look for alternatives.” Lacking relatives or contacts in the United States who might wire money, many of the Venezuelan migrants are selling items like candy on the streets in order to earn enough to pay the Nicaraguan authorities.

These reports from along the migrant route indicate that the flow of Venezuelan migrants now being experienced in El Paso and elsewhere along the U.S.-Mexico border is not ebbing. It is likely to intensify further in the coming weeks.