With this series of weekly updates, WOLA seeks to cover the most important developments at the U.S.-Mexico border. See past weekly updates here.

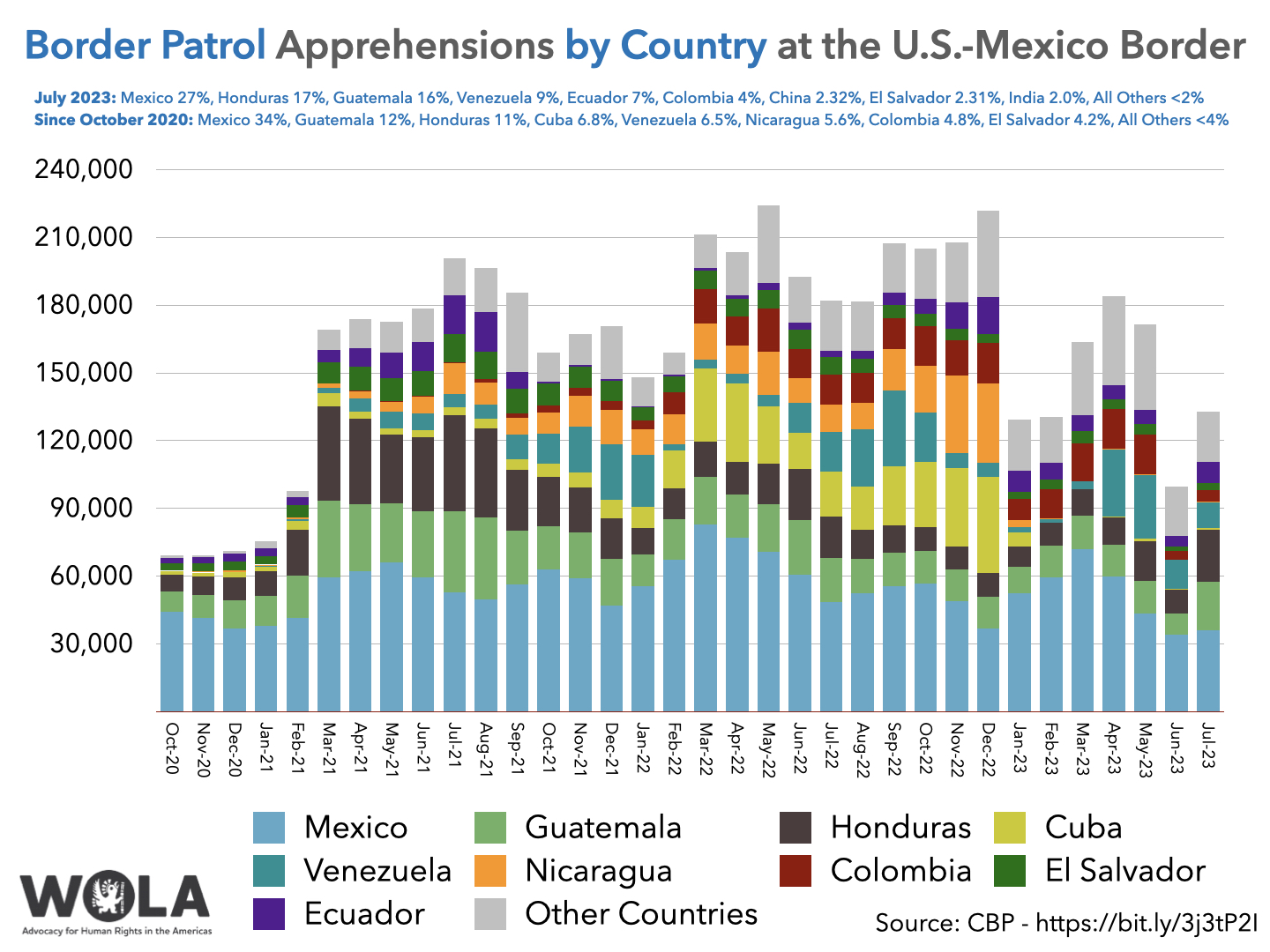

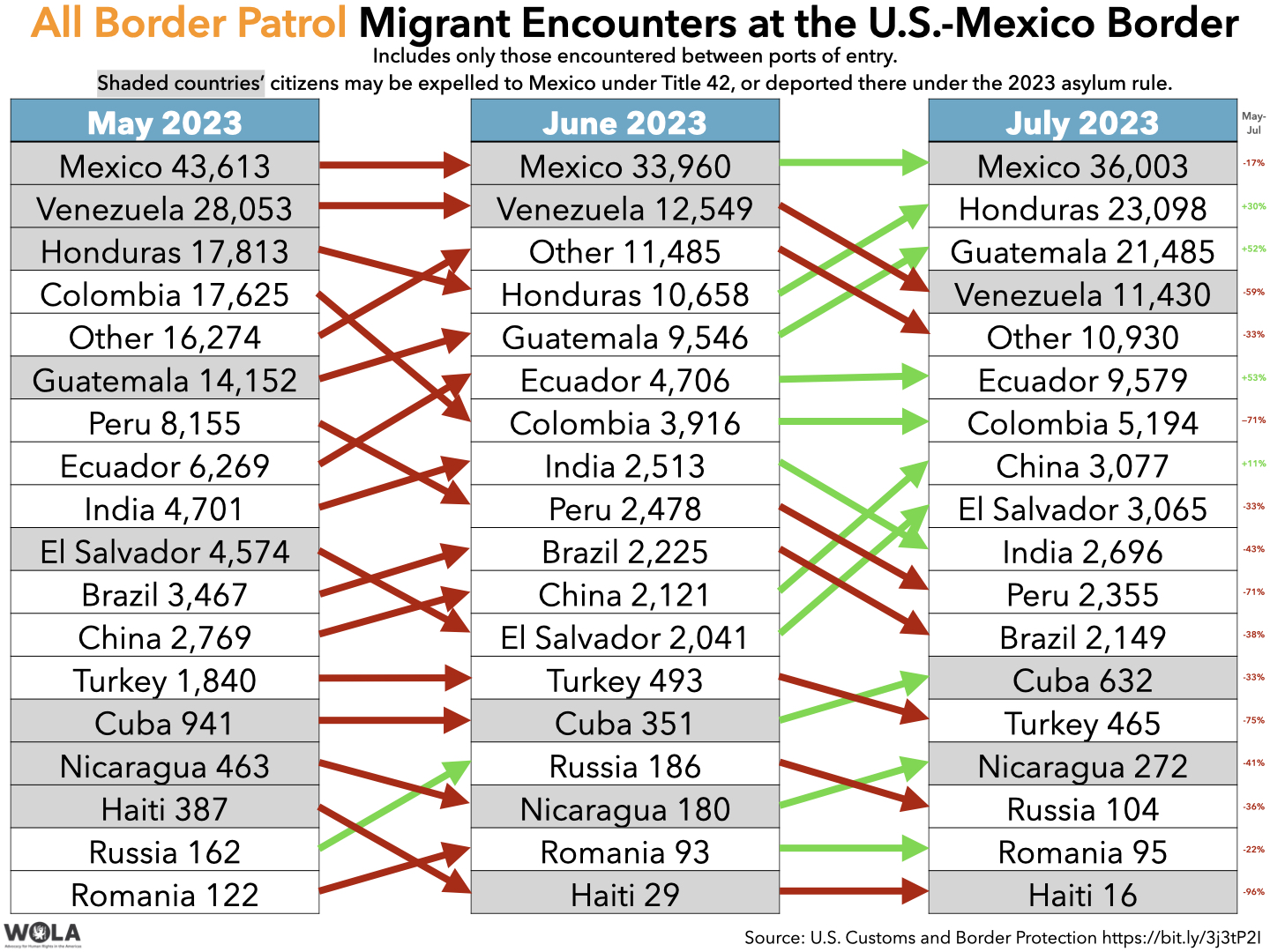

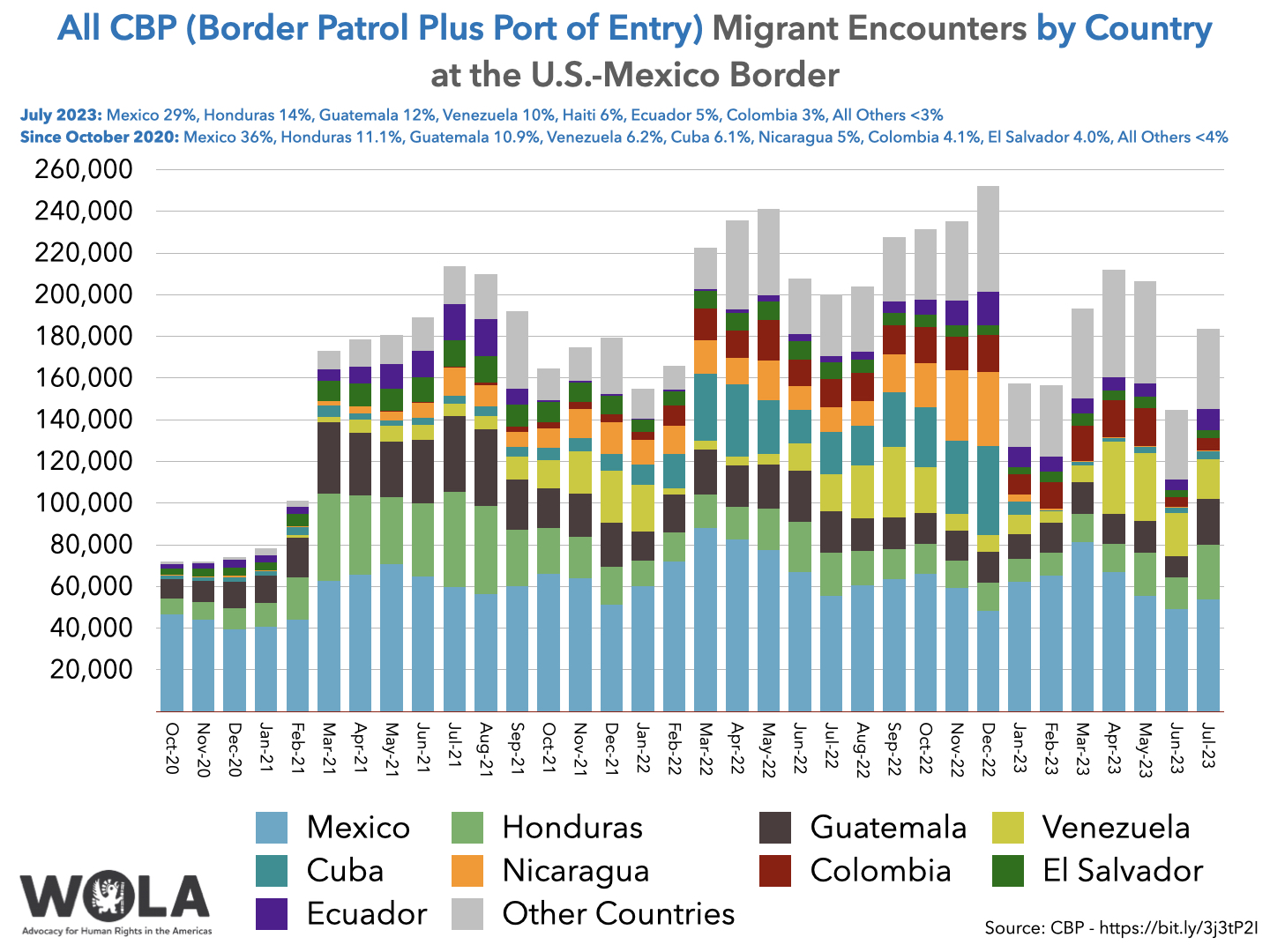

Border Patrol’s apprehensions of migrants between ports of entry increased 33 percent from June to July. While still far fewer than in July 2022, the numbers signal that a post-Title 42 lull in migration has come to an end. Nearly all of the increase was arrivals of children and families, with Ecuador, Guatemala, and Honduras the nationalities whose numbers grew the most. Though large numbers of Venezuelan migrants are en route to the border, the number of Venezuelan migrant encounters actually declined. More than 50,000 people were processed at ports of entry, a record.

The Justice Department’s lawsuit against the state of Texas, seeking to compel Gov. Greg Abbott (R) to remove a “wall” of buoys in the Rio Grande in Eagle Pass, went before a federal judge in Austin. Texas’s attorneys were not permitted to use their “invasion defense” argument to justify the barrier’s placement. This is one of several recent controversies surrounding Gov. Abbott’s “Operation Lone Star” security buildup.

Mexico’s immigration agency and Catholic Charities of the Rio Grande Valley opened a facility, on the grounds of an unused hospital, in Matamoros, Tamaulipas, across the river from Brownsville, Texas. The site intends to provide an alternative to a sprawling tent encampment that has formed along the Rio Grande in Matamoros, as asylum seekers there struggle to secure appointments using the CBP One smartphone app.

Customs and Border Protection (CBP) released data on August 18 revealing a 33 percent increase in July, compared to June, in the number of migrants whom U.S. Border Patrol apprehended between the U.S.-Mexico border’s ports of entry (99,539 to 132,652).

Data table

Data table

This was still 27 percent fewer migrants than a year ago, in July 2022 (181,834), when the Title 42 pandemic expulsions policy was in full effect. In July 2023, 9 percent of migrants had been encountered at least once before in the previous 12 months; that was way down from 22 percent in July 2022. This “recidivism” number was much higher during the Title 42 period, when quick expulsions eased repeat crossings.

Data table

Data table

The sharp increase over June indicates an end to the sharp drop in migration that followed Title 42’s May 11, 2023 termination. July’s partially recovered migration flow differs from the pre-May 11 period, though, in its demographic makeup, in the part of the border where migrants are arriving, in migrants’ ability to use ports of entry, and to some extent by migrants’ nationalities.

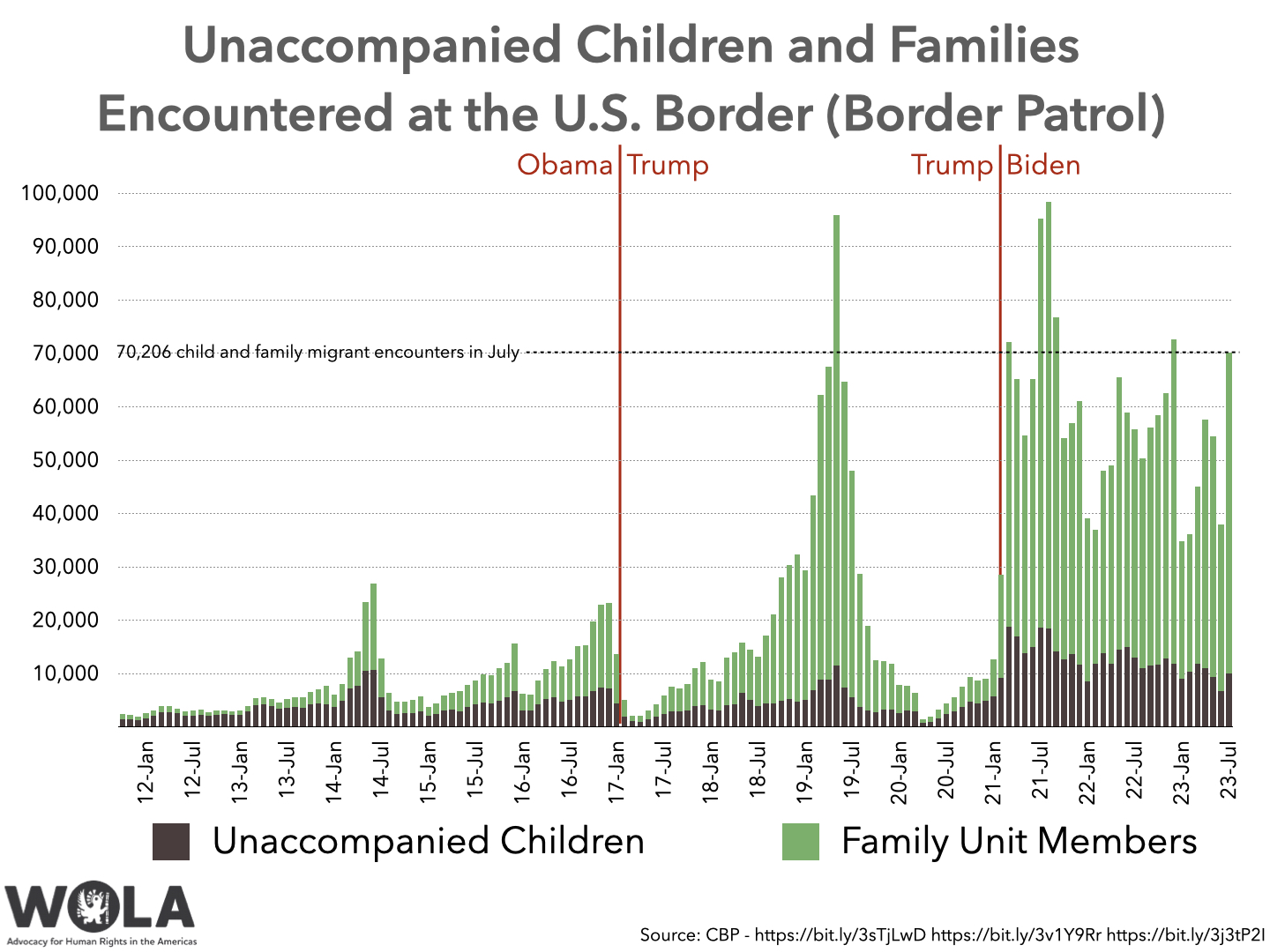

Nearly all of the July increase was child and family migrants, whose numbers grew 85 percent from June to July (38,002 to 70,206, combining family-unit members and unaccompanied children). The 60,161 family-unit members apprehended in July 2023 were the most in a single month since December 2022, and before that since September 2021.

Border Patrol’s July apprehensions of single adults (62,446), meanwhile, barely budged, increasing 1 percent over June and remaining 51 percent below April 2023, the Title 42 policy’s last full month (126,402).

Data table

Data table

Following Title 42, the Biden administration put in place an administrative rule that bans access to asylum for most migrants who show up at the border between ports of entry, ending up in Border Patrol custody. Those migrants face a high probability of deportation—including deportation into Mexico if they are from Mexico, Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua, or Venezuela.

For the most part, CBP has so far been applying that ban principally to single adults. Luis Miranda, the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) principal deputy assistant secretary for communications, told Spanish-language reporters on August 17 that smugglers are misinterpreting that in their messaging to migrants: “smugglers have lied to the people saying that there are not going to be consequences for people arriving in family groups. And we want to make it clear that that is not true.”

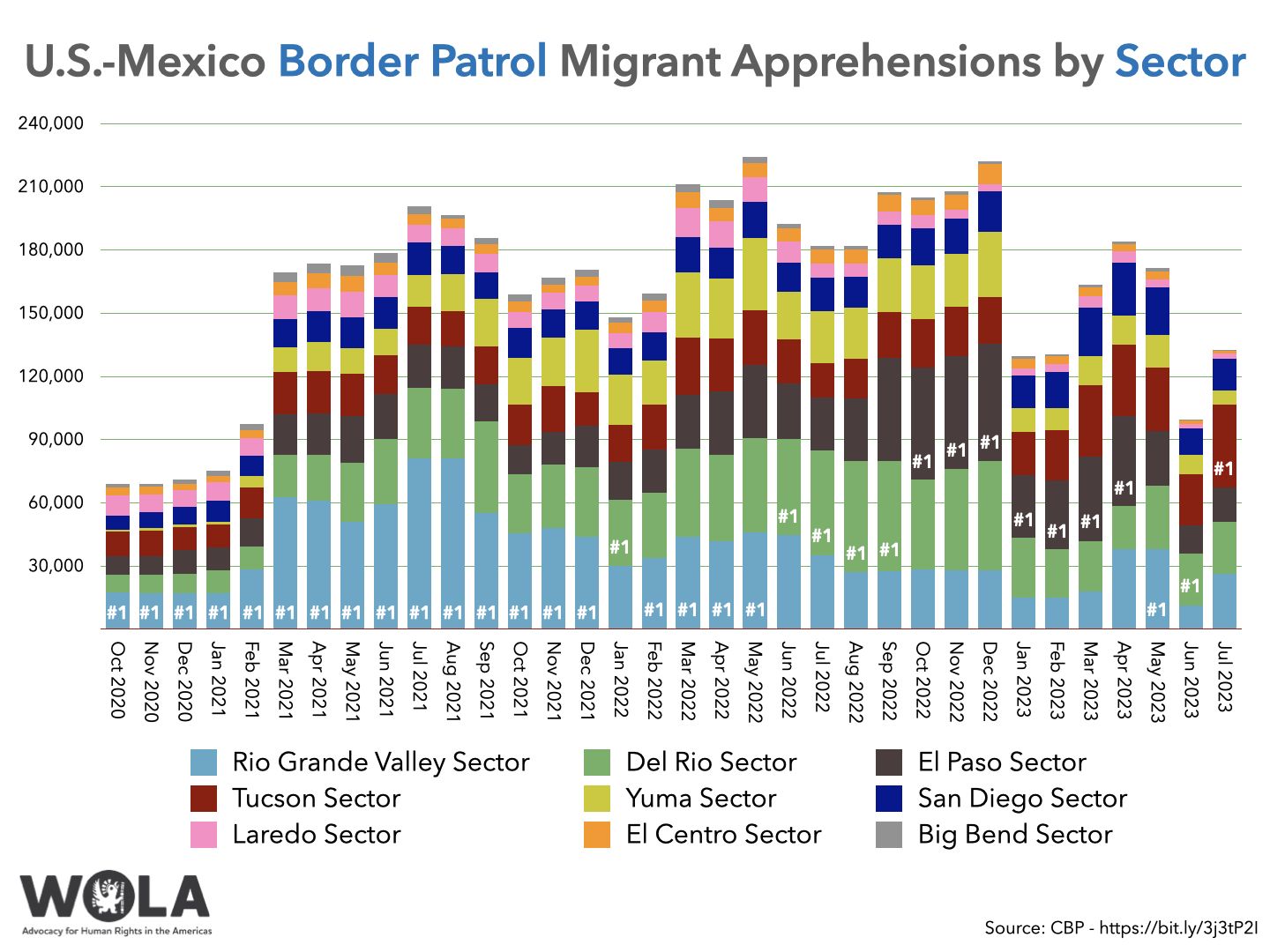

Border Patrol divides the U.S.-Mexico border into nine sectors. As noted in WOLA’s August 11 Border Update, post-Title 42 migration shifted dramatically to the agency’s Tucson Sector, which comprises most of Arizona’s border, despite record heat in the state’s deserts in July. Tucson (red in the chart below) was in fifth place among the nine sectors as recently as November 2022, but occupied first place by far in July (39,215 migrant apprehensions, well ahead of Texas’s Rio Grande Valley Sector, in second place with 26,528).

Data table

Data table

During the past 14 months, 4 different sectors have been the number-one monthly destination for migrants at the U.S.-Mexico border. This wild variation is new: the Rio Grande Valley Sector was consistently the number-one destination between March 2013 and December 2021, and before that, the Tucson Sector was first since 1998.

The main nationalities of migrants apprehended in the Tucson Sector in July were Mexico (40 percent), Guatemala (19 percent), Ecuador (16 percent), and India (5 percent), with 13 percent coming from countries that CBP lists as “Other” because they did not come to the border in significant numbers in past years.

Just 46 percent of Border Patrol’s July Tucson apprehensions were of single adults (18,073). 48 percent were family-unit members (18,916) and 6 percent were unaccompanied children (2,226).

According to CBS News, an unnamed CBP official told reporters on August 18 that smugglers are behind the shift to Arizona: “We have seen the human smugglers’ attempts to direct migrants toward that, and advertising to people that it is somehow an area that they can expect greater success crossing into the country. That is not true.”

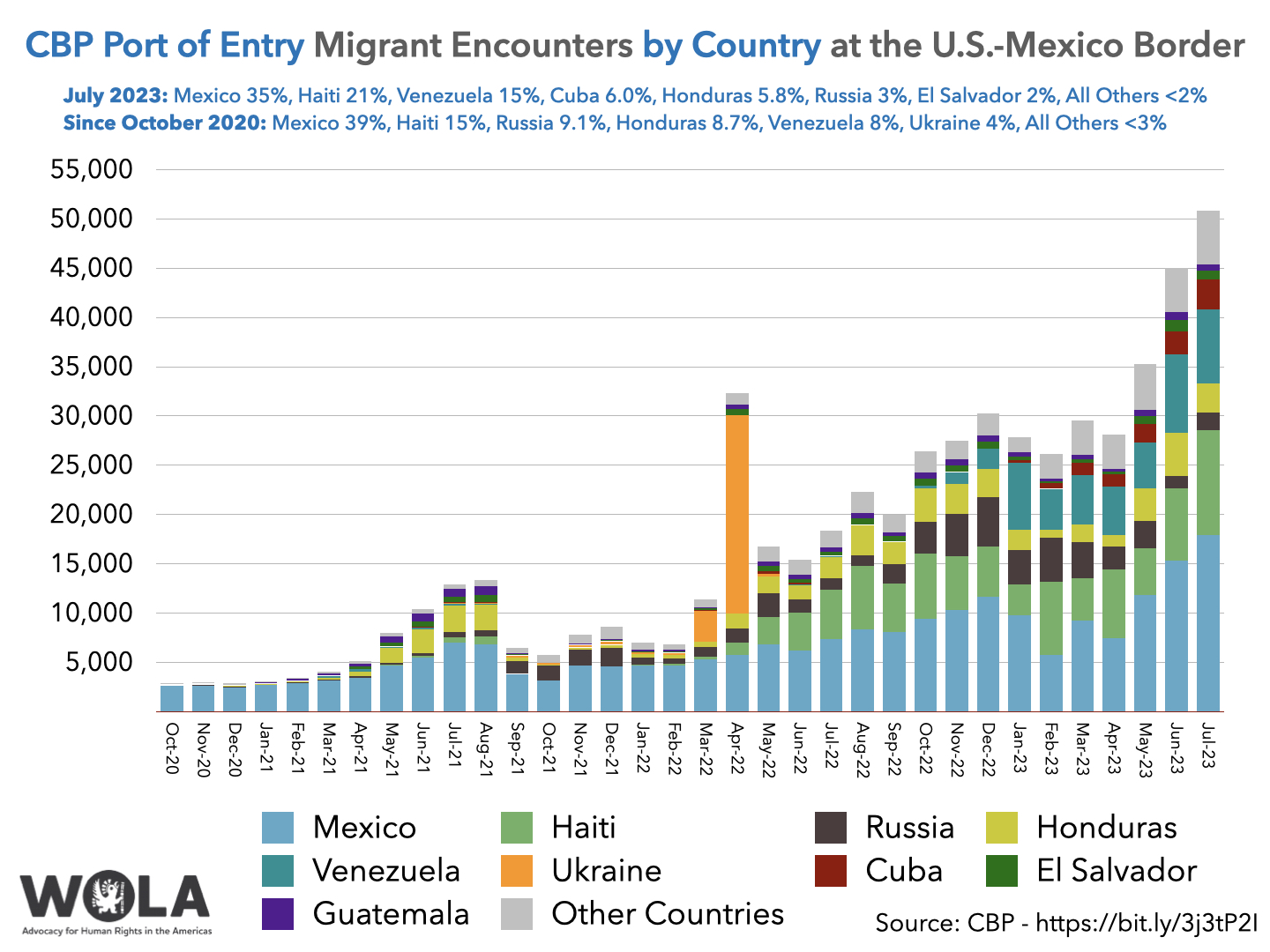

A record 50,851 migrants were able to approach the ports of entry (official border crossings), ending up processed by CBP’s Office of Field Operations, not Border Patrol. The vast majority—88 percent, or over 44,700—made appointments using the CBP One smartphone app. CBP reported a total of 188,500 individual CBP One appointments between January, when the app’s appointments feature was rolled out, and the end of July.

Data table

Data table

“Effective August 9, CBP transitioned to scheduling appointments from 14 days to 21 days in advance to allow noncitizens additional time to prepare and arrange travel to their requested port of entry,” reads CBP’s release announcing July’s numbers. “This change will be reflected in next month’s statistics,” which may show a drop in CBP One appointments from July.

The nationalities whose citizens reported most often to ports of entry in July were Haiti (99.9 percent of all encountered Haitian migrants), Russia (94 percent), and Cuba (83 percent). Large numbers of citizens of Mexico (17,932) and Honduras (2,934) also presented at the ports, but much larger numbers of those countries’ citizens ended up in Border Patrol custody, between the ports.

“U.S. authorities say it generally takes six to eight weeks of daily attempts to get an appointment on CBP One,” the Associated Press reported from Matamoros, Tamaulipas, across from Brownsville, Texas, on August 23. “Many migrants interviewed by The Associated Press said they have been trying around three months, though some said they have gotten lucky after only a few days of trying.”

Between the ports of entry, Border Patrol’s apprehensions of citizens of Guatemala, Honduras, and Ecuador more than doubled from June to July. Though their numbers were smaller, apprehensions of citizens of Cuba, El Salvador, and Nicaragua also increased by at least 50 percent from June.

Of Border Patrol’s July apprehensions of migrants from those six high-growth countries (58,131 total), 76 percent were members of family units (36,777) or unaccompanied children (7,555).

Combining Border Patrol’s apprehensions and CBP’s port-of-entry encounters yields a total of 183,503 encounters with migrants at the U.S.-Mexico border in July. That represents a 27 percent increase over June but an 8 percent drop from July 2022.

Data table

Data table

One of the only nationalities to measure a June-July drop in migration was Venezuela (-7 percent). This is surprising, since data along the U.S.-bound migrant route show large numbers of Venezuelan citizens en route:

This would seem to point to a large number of Venezuelan migrants stranded along the way—many of them probably in Mexico—unable to seek protection in the United States without CBP One appointments due to the Biden administration’s asylum rule. (Mexico has not yet reported its July migrant apprehensions.)

That rule “has reduced irregular migration since it was implemented,” DHS’s Miranda told reporters on August 17. “We’ve now deported more than 145,000 people since May 12.”

That number includes people deported from the border by air to their home countries, citizens of Mexico deported back across the border, and citizens of the four countries whose citizens Mexico allows to be deported: Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua, and Venezuela.

We have not seen data detailing those deportations back into Mexico.

“The number of attempted border crossings per day has crept back up from its post-Title 42 low of 4,000 per day to 8,000,” according to the same NBC News report. If that is truly accurate over 31 days, it would mean about 240,000 migrant encounters in August—a big jump from July’s 183,503 encounters (combining Border Patrol and ports of entry).

In Austin on August 22, federal District Judge David Ezra heard arguments in the Justice Department’s lawsuit against Texas’s state government, seeking to compel Gov. Greg Abbott (R) to take down a 1,000-foot “wall of buoys” strung down the middle of the Rio Grande in Eagle Pass.

Abbott, an immigration hardliner who frequently litigates against the Biden administration’s border policies, had installed the bright orange buoys, with sharp discs between the spheres, in July. (See WOLA’s July 14 Border Update.) The Justice Department ordered Abbott to take the buoys down because the project appears to violate the Rivers and Harbors Act of 1899, which gives the federal government control of navigable waterways like the Rio Grande. Abbott refused.

Justice Department attorneys made those points in Judge Ezra’s courtroom. Hillary Quam, the State Department’s U.S.-Mexico border affairs coordinator, testified that Abbott’s buoys are harming relations with Mexico. She noted that the government of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador has sent three diplomatic notes about the subject since June, and raised it repeatedly during presidential press conferences and in recent meetings with U.S. cabinet secretaries. Mexico contended that some of the buoys are on Mexico’s side of the river, and that the unilaterally-installed barrier, with netting going all the way down to concrete blocks on the riverbed, could alter the river’s flow.

As noted in WOLA’s August 18 Border Update, the Justice Department submitted a July 27-28 International Boundary and Water Commission survey showing that nearly 80 percent of the buoys were actually on Mexico’s side of the river. Over the August 19-20 weekend, Texas quietly moved the buoys’ concrete blocks further back onto the U.S. side of the river. “There were allegations, which I don’t know if they were true or not, but allegations that the buoys had drifted toward the Mexico side,” the governor said on August 21, without explaining how concrete blocks could have drifted. “And so out of an abundance of caution, Texas went back and moved the buoys into a location where it is clear that they are on the United States side, not on the Mexico side.”

Texas’s written arguments in the case contend that the state is using its constitutional authority to respond to an “invasion,” a controversial line of argument—portraying Eagle Pass’s predominantly asylum seeking migrants as invaders— promoted by think tanks supportive of ex-president Donald Trump. (The “buoy wall” concept, developed by contractor Cochrane International, was under Border Patrol’s serious consideration during Trump’s administration, the agency’s chief at the time, Rodney Scott, told NBC News.)

Texas’s attorneys did not push hard on the “invasion” or “war powers” line of argument in the August 22 hearing, and Judge Ezra, a Reagan appointee, appeared uninterested in considering it. “This is a United States District Court. It is not Congress. It is not the President,” the judge said. “I’m not here to engage in nor do I have any inclination to engage in any type of political comment in this decision.”

Judge Ezra gave both sides until August 25 to submit written closing arguments, and he may rule on the buoys’ legality as early as next week.

The suit does not cover Texas’s use of dozens of miles of razor-sharp concertina wire in the river and on its banks in Eagle Pass, which has wounded many asylum seekers trying to reach U.S. soil. (See WOLA’s July 21 Border Update; Border Report on August 21 reported witnessing several migrants who “suffered cut feet and legs from trying to climb the concertina wire at a gap in the fencing”). This week, Texas national guardsmen began installing a new wall of concertina wire along the river in El Paso.

Gov. Abbott was in Eagle Pass on August 21, hosting the Republican governors of Iowa, Nebraska, Oklahoma, and South Dakota for a photo op near the buoys. “All four visiting governors declared the immigration situation on the South Texas border a ‘crisis’ and used words like ‘war zone’ and ‘ground zero’ to describe the situation,” observed Border Report’s Sandra Sánchez.

The hearing was not the only controversy surrounding Gov. Abbott’s “Operation Lone Star” border security program during the past week, one week after a three-year-old Venezuelan girl died aboard a Texas bus transporting asylum seekers to Chicago (see WOLA’s August 18 Border Update).

Reporting for the New York Times from Eagle Pass, where the majority of the population is Mexican-American, Edgar Sandoval found support for “Operation Lone Star” to be “waning,” noting that “some Eagle Pass residents said it has come to feel as if their own town is under siege.” Still, a Los Angeles Times column from Jean Guerrero recalled that Abbott’s measures have the support of a substantial minority of Texas’s Latino population: a June 2023 University of Texas-Austin poll found 36 percent of Latino respondents believing “the state is spending too little on border security.” Guerrero observed: “With regional roots dating as far back as the 1500s, Texans of Latino ancestry will often identify as Tejano above all. They are less likely to see themselves in immigrants.”

Mexico’s immigration agency (Instituto Nacional de Migracion, INM) and Catholic Charities of the Rio Grande Valley have opened up a sheltered tent facility for migrants currently stranded, waiting for asylum appointments, in Matamoros, Tamaulipas, across from Brownsville, Texas. The site, on the grounds of an unused hospital, is meant to substitute for a squalid, mile-long tent encampment that formed several months ago along the Rio Grande.

The new site’s capacity is 850 people. “On the first day,” the Associated Press reported, “500 Haitians who were living at an old gas station and about 150 people who camped by the river moved in.” The INM stated that as of August 16, 597 migrants were there, from Honduras, El Salvador, Haiti, Colombia, Mexico, Guatemala, Venezuela, Nicaragua, Cuba, Peru, and Ecuador.

Matamoros, Mexico’s easternmost border city, has long been under the influence of the Gulf Cartel, an organized crime group. Migrants often feel unsafe in the city, where ransom kidnappings and other attacks are common. “Those who have coveted CBP One appointments become kidnapping targets” in Matamoros, according to the AP. That is a key reason why well over 1,000 had gathered at the riverside tent encampment, which they are now being encouraged to abandon to move to the new facility, which has a guarded perimeter.

Not all are willing to leave the encampment. Some told AP that they distrust Mexican authorities: being in a facility run by the INM, they worry, could make them easier to deport. Others prefer not to live at a site with tight curfews and supervision.