The Americas are facing unprecedented levels of migration. Many migrants and asylum seekers are coming to the United States. But most are seeking refuge in neighboring countries. Here is some data to put this moment in context.

1. Most migrants arriving in the United States are exercising their right to seek asylum

Asylum is a right guaranteed by law.

- It is a standard that emerged after World War II, when countries agreed that they would never again close their borders to people in danger. The United States ratified the Refugee Convention in 1968, and passed the Refugee Act in 1980. They say that if you’re on U.S. soil and fear loss of life or freedom if you’re returned to your country—for reasons of race, religion, nationality, political belief, or membership in a social group—then you have the right to petition for asylum and receive due process. And it doesn’t matter how you reached U.S. soil.

Most people coming to the United States are turning themselves in to authorities on arrival and asking for asylum.

- In August 2023, U.S. authorities encountered 232,972 people seeking to migrate at the U.S.-Mexico border. 56 percent were children, or parents and children. Most were seeking asylum: 145,278 were released into the U.S. interior with notices to appear in immigration court.

- According to the latest asylum data, 49 percent of those seeking protection in the United States whose cases reached a decision received asylum or another form of relief during FY2023.

Other countries are seeing the same phenomenon.

- “These are unprecedented times, never in human history have we had so many migrants on the move as we do right now,” Assistant Secretary of State for Western Hemisphere Affairs Brian Nichols said on October 10. “Some 28 million migrants in our hemisphere are moving for a variety of reasons.”

- Colombia: more than 5 percent of the population came from Venezuela since the mid-2010s.

- Costa Rica: 253,000 people or 5 percent of the population have applied for asylum in Costa Rica since 2018.

- Mexico: at current rates, over 150,000 people—a record by far— will apply for asylum in Mexico by the end of 2023.

- The number of recently arrived Venezuelan citizens living in the United States is approaching 1 million (adding the roughly half million who were here in 2021 to the 450,000 who have arrived since 2022). But for every Venezuelan settling here, more than 6.5 million Venezuelans are living elsewhere, in Latin America and Europe.

2. The United States needs to invest in managing, in a humane and timely manner, migrants and asylum seekers—NOT in more border security

A large-scale arrival of asylum-seeking migrants will always pose a challenge. But it would be manageable if the U.S. government invested in the personnel and infrastructure necessary for processing, alternatives to detention, and adjudication.

- 659 immigration judges are currently trying to work through a backlog of 2.1 million cases, including at least 850,000 pending asylum cases.

- Border Patrol has hired about 1,000 civilian “processing coordinators” to work with migrants who turn themselves in at the border. But that is nowhere near enough: most processing paperwork is still filled out by armed, uniformed agents whose academy training focuses on law enforcement skills. If those agents could be put back on the line while others do processing, there would be no shortage of agents.

Instead of addressing this, the United States is tackling migration as an enforcement problem: The U.S.-Mexico border has already seen an enormous security buildup over the past 30 years. Border Patrol quintupled in size, to nearly 20,000 agents. About 741 miles of wall have been built, bristling with high-tech cameras and sensors.

- Today, we have a border that is well equipped to capture and jail drug smugglers, single adult economic migrants, and—according to the big post-September 11, 2001 funding increases—terrorists, but not to handle vulnerable asylum seekers.

A majority of the migrants arriving at the border are pursuing asylum cases, either from ICE detention or released into the U.S. interior. In August, the majority were children, or parents with children from multiple nationalities.

- This changed profile of migrants is no longer a new trend: the first significant jump in child and family migration, and in non-Mexican migration, happened during the Obama administration, in late 2013 and early 2014.

3. Legislative proposals from “border hawks,” like the “Secure the Border Act” (H.R2), would endanger thousands of lives

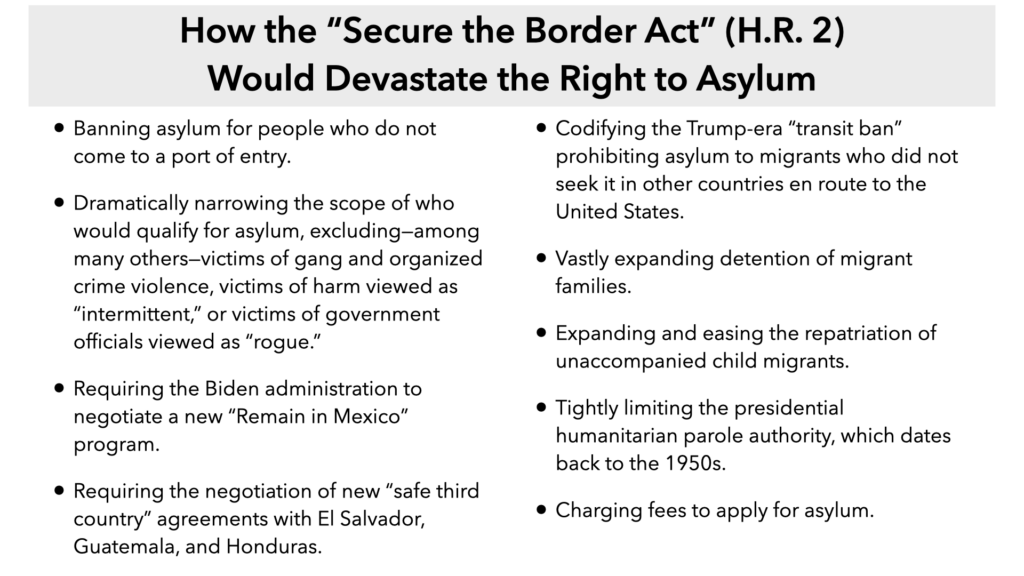

On May 11, the House of Representatives passed the “Secure the Border Act” (H.R. 2) on a party-line vote of 219-213. Two Republican members, and all Democrats, voted against this bill, which would almost completely roll back the right to seek asylum to people on U.S. soil asking for protection.

People would die as a result of these measures.

People would die as a result of these measures.

- For fiscal year 2023 in U.S. immigration courts, 49 percent of asylum cases that reached a decision resulted in grants of asylum or other protection. 31,459 people between October and August have avoided death, torture, or severe harm because of existing asylum laws and procedures. [1]

- Had legislation like H.R. 2 passed, putting asylum out of reach for nearly all applicants in a misguided attempt to “deter” them, most of those 31,459 people would have been sent back to certain danger.

These hardline approaches haven’t even reduced migration anyway.

- Since 2014 we’ve seen—among other deterrence schemes—Mexico’s U.S.-backed “Southern Border Plan,” family detention facilities, cruel family separations, the “Remain in Mexico” policy, the Title 42 pandemic expulsions policy, and the Biden administration’s asylum “transit ban.”

- None have reduced migration for more than a matter of months. Arrivals at the U.S.-Mexico border just keep increasing, because push factors like insecurity and poverty—and the weak rule of law, corruption, inequality, and climate crisis that worsen them—remain unaddressed.

Conclusion: There is no amount of suffering the U.S. government can impose that’s more severe than life in a gang-dominated slum, or under a vicious dictatorship, or under a government that persecutes one’s ethnic group, religious identity, gender, sexual orientation, or political affiliation, or other forms of violence or persecution under governments that are either unwilling or unable to protect their citizens.

“I’ve heard some people talking about migration control, closing borders, and we know that it doesn’t work,” Ugochi Daniels, the International Organization for Migration’s deputy director of operations, recently told the Associated Press. “We know that what people will do is still find a way to move, but it will be more risky and they’ll be more vulnerable. You can’t control migration; you can manage it.”

[1] Not all cases end in decisions: as many as half get classified as “other” due to dismissal, closure, or other reasons, according to the Congressional Research Service, which points out that in many “other” cases, the migrant still “may be able to remain in the United States.”