(AP Photo/Ramon Espinosa)

(AP Photo/Ramon Espinosa)

The Biden Administration’s decision to gradually increase staffing at the U.S. embassy in Havana, Cuba, and expand consular services is a welcomed step forward. Cubans are privileged among other groups of Latin American migrants because they have a viable migration channel through current U.S. visa policies. However, without a clear timeline to restart and fully regularize consular services, it will continue to add further strain on an already overwhelmed and flawed system, and to push Cubans to follow irregular and dangerous methods of migration.

Immigration policies have long been a sore point in the U.S.-Cuba relationship.

Since the 1960’s, the United States has maintained a preferential relationship with Cuban citizens and facilitated a direct path to permanent residency. The Cuban Adjustment Act, effective since November 2, 1966, allows Cuban natives or citizens who have been physically present in the United States for at least a year to apply to become lawful permanent residents. This fast-track path to permanent residency—in addition to Cubans wanting to flee the country for political and economic reasons—has led to mass migration of Cubans to the U.S.

After the 1959 Cuban revolution, approximately 1.4 million people fled to the United States, the largest migrant flow in the Caribbean country’s history. Since then, Cubans have remained one of the top populations of migrants to reach the U.S. A number of tragic incidents involving Cubans trying to reach the U.S. by sea led President Clinton to announce that Cubans interdicted at sea would be sent to the U.S. Naval Base in Guantánamo. It was then that the so-called wet foot/dry foot policy was born, which granted Cubans who reached U.S. soil by foot, the right to stay and get on a fast track to citizenship. On paper, the policy aimed at discouraging people from taking the risky journey by sea. Under an accord signed in September 1994, the United States agreed to legally admit at least 20,000 Cubans—not including immediate relatives of U.S. citizens—per year and Cuba pledged to prevent further irregular departures by rafters.

In 2007, in order to meet immigrant visa requirements under the US-Cuba migration accords, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services launched the Cuban Family Reunification Parole Program (CFRP) that allows family members of U.S. citizens and permanent legal residents to travel to the United States without having to wait for their immigrant visas to be granted. Once in the United States, CFRP program beneficiaries may apply for work permits while they wait to apply for lawful permanent resident status under the Cuban Adjustment Act.

Things changed in 2013.

Following the liberalization of rules that had restricted travel out of the island, the number of Cubans trying to reach the U.S. via Mexico and relying on the wet-foot/dry-foot policy increased. But, in the final days of his administration, President Obama abruptly put an end to this policy, a capstone to his two-year-old effort to re-establish relations with Cuba. This led to a sharp increase in Cubans seeking asylum, and deportation cases went from 388 in 2016 to 24,198 in 2019.

The situation took a further downturn in 2017, when under the Trump administration, the U.S. suspended visa processing at the Embassy in Cuba indefinitely and halted all consular services in response to the “Havana Syndrome,” a “mysterious ailment” allegedly affecting embassy staff and their relatives. A preliminary report published by the CIA in February 2022 found that most cases were likely to have been caused by any foreign influence. The Embassy’s closure has continued to be a detriment to the tens of thousands of Cuban immigrants who continue to await their visas to reunite with their families in the U.S.

Toward the end of 2021, the Biden administration reinstated the “Remain in Mexico” policy under court orders, promptly restarting the return of U.S.-bound asylum seekers to Mexico to wait for a resolution of their case in U.S. immigration courts. Throughout 2022, Cubans continue to be among the top nationalities enrolled in the Remain in Mexico program, alongside nationals from Nicaragua, Venezuela, Colombia and Ecuador. Because of the difficulties in accessing the U.S. asylum system and in reaching the U.S.-Mexico border as a result of the increased migration enforcement in Mexico, many Cubans are also opting to seek protection in Mexico. In 2021, Mexico’s refugee agency, COMAR, received 8,319 asylum requests from Cubans, up from 5,725 in 2020, and granted asylum in 69 percent of the cases, an increase in approval rates as compared to previous years. As many as 2,004 Cubans requested asylum in Mexico in the first two months of 2022 alone.

The continued migration flows of Cubans, both to the U.S. and Mexico, highlight the need for effective pathways for legal migration. Their unique standing within the U.S. immigration system should be a tool to provide stability and security for those choosing to leave their home country—not an additional barrier to their safety.

According to an analysis by the Cuba Study Group, increasing numbers of people between 20 and 40 years of age, and women are the ones making up the bulk of those migrating

This raises concerns over the lack of caretakers for aging populations with a significant number of elderly Cubans left without family members on the island to care for them, according to the last ENEP survey. Elderly single-person households rose from 12.6 percent in 2012 to 17.4 percent in 2019, and as women continue to be the main source of care for the elderly, their exit will have important implications for the future of this population. It is important to note that within Cuban society, emigration is also seen as one of the main sources for survival. As strict limits on remittances from the U.S. remain in place, this survival strategy will be challenged.

The largest migration waves of Cubans have coincided with moments of crisis in the country’s economy and deteriorating standards of living, conditions that are present once again. The island is currently experiencing the worst economic and humanitarian crisis since the 1990s, made worse by the ongoing impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite significant levels of vaccination and stabilizing COVID-19 cases, the decreasing resources and medical supplies coupled with significant episodes of social unrest continue to push Cubans to leave the island. U.S. restrictions on remittances and people-to-people travel continue to impact what was once a burgeoning private sector. In 2020, the Cuban economy shrank 11 percent, and inflation in 2021 reached 71 percent as a result of the process of currency reunification.

One of the hardest hit sectors remains the tourism industry, which accounts for 10 percent of the country’s GDP, and is a critical source of revenue for the government for purchasing food and medicine internationally. Cuba kept its borders largely shut until November of 2021, and has not seen the necessary bounce-back of the industry to move beyond the economic obstacles of the last years. This, coupled with the difficulties of production during the pandemic—which is, in turn, compounded by the U.S. embargo and additional sanctions—has deepened the lack of basic necessities for Cubans. As the economic and humanitarian crisis deepens with little hope for relief, Cubans feel forced to look for stability elsewhere.

For many years, Cubans began their journey to the U.S. border in South America. Guyana was and continues to be a frequent starting point as it is the only country in continental South America where they can be admitted without a visa. Things changed in November 2021, when Nicaragua lifted visa requirements for Cuban nationals, opening a new, and shorter, path to reach the U.S. The new route allowed people to avoid crossing the infamous Darrien Gap, a dangerous jungle that connects Colombia and Panama. As many as 130,000 people, including 15,000 Cubans crossed the Darien Gap in 2021, according to figures from the Panamanian National Border Services (Senafront), reported in local media. This represented a sharp rise from the around 1,000 Cubans who attempted the same journey in 2016. Notwithstanding the visa waiver for Cubans to enter Nicaragua, new transit visas required by Costa Rica and Panama have posed additional challenges for travelers.

In addition, attempting to reach the U.S. by sea continues to be increasingly challenging. In response to the unrest in Cuba last July, the Secretary of the Department of Homeland Security, Alejandro Mayorkas, released a statement stressing that any migrant intercepted at sea would not be permitted to enter the United States. According to recent figures by the U.S. Coast Guard, 852 Cubans have been intercepted at sea since October 2021, compared to 839 in the entire 2021 fiscal year.

Cuban authorities confirmed that 1,255 migrants returned to Havana in 2021 in bilateral operations coordinated with the United States, Mexico, the Cayman Islands and the Bahamas. So far in 2022, 861 Cubans have been returned, 345 by the U.S. Coast Guard, 473 by Mexico and 43 by the Bahamas.

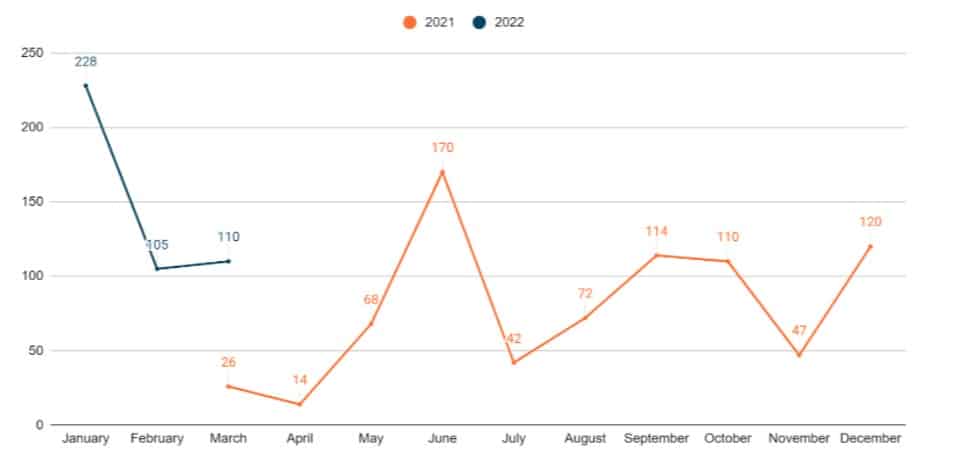

Data provided by the U.S. Coast Guard and compiled by WOLA.

Data provided by the U.S. Coast Guard and compiled by WOLA.

The embargo that has been in place over the last 60 years has undoubtedly exacerbated the conditions under which Cubans feel forced to migrate. The current humanitarian crisis on the island is worsened by the inability to import basic necessities, including food and medicine, under the onerous sanction apparatus the U.S. has imposed on Cuba. Humanitarian assistance is extremely limited to those that understand and can operate under the delicate Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) restrictions in place, and in many cases, their ability to do so is subject to bureaucratic challenges to obtain the necessary permits and equipment to send to Cuba.

In addition, Cuba’s designation as a State Sponsor of Terrorism (SSOT), announced by the Trump administration in his last days in office and which has not been reversed by the Biden administration, creates further obstacles to purchasing or receiving these goods. Remittances and travel to the island, which are historically the most prominent ways those outside the country could support their families and loved ones, has also been severely curtailed since the Trump administration’s decisions to rollback on Obama-era policies.

The closure of the U.S. Embassy in Havana also meant that the 20,000 visas allotted to Cubans were continuously underused. Cubans looking for U.S. consular services were referred to the U.S. Embassy in Guyana, creating additional obstacles to those looking for legal pathways to migration. As a result, many decided to travel irregularly to solicit asylum at the U.S.-Mexico border, as detailed above. As the rise in numbers of Cuban migrants surged through more traditional irregular routes, so did the risk of being exploited by smugglers and organized crime groups along the way. Cubans in particular appear to be at an increased risk of extortion and kidnapping as they are thought to have U.S.-based family members with the resources to pay ransom.

To alleviate these risks and minimize irregular migrations flows from Cuba to the U.S, the Biden administration should regularize consular services in a timely manner. The recent announcement of restarting services in the U.S. Embassy in Havana should be the first step of many in providing regular and reliable services to those seeking to emigrate to the U.S. The Cuban Family Reunification Parole Program should also be used to its fullest extent.

Outside of actions that relate explicitly to migration policies, steps to normalize relations between the two countries would also go a long way to mitigate the humanitarian and economic situation that has forced many Cubans to leave. The administration should suspend U.S. regulations that prevent food, medicine, and other humanitarian assistance from reaching the Cuban people and remove all restrictions on family and non-family remittances. Additionally, it should eliminate Trump-era policies that restrict travel to Cuba, since they make it more difficult for Cuban-Americans to visit and reunite with family on the island, particularly for those with families outside of Havana, and limit mutually beneficial dialogue between the U.S. and Cuban people.