Photo: CBP; Illustration: Sergio Ortiz Borbolla

Photo: CBP; Illustration: Sergio Ortiz Borbolla

This report is a product of our organizations’ years of work documenting human rights violations committed by U.S. federal law enforcement forces at the U.S.-Mexico border.

We offer this report in the belief that it is possible to enact common-sense reforms that stop cruelty and align border governance with democratic values, even at a time when larger national debates on border and immigration policy are polarized and paralyzed. Regardless of where they stand politically, we believe that nearly all Americans—and nearly all employees of U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and its Border Patrol agency—agree that the abuses and behaviors described here are unacceptable. We believe that nearly all might share our view that this report’s described “failure points” on accountability are fixable.

We hope that this report inspires, energizes, and offers a roadmap to advocates, scholars, journalists, legislative oversight staff, executive-branch policymakers, and others who agree that the present state of abuse and accountability at the U.S.-Mexico border demands deep reform. We publish with a key audience in mind: the agents and officers, at all levels of CBP and Border Patrol, who seek to do their job honorably and without a political agenda, and who recognize the harm that persistent impunity does to their institutions.

We have documented a reality that—when viewed together, not as a drumbeat of isolated episodes—is frankly shocking. High-profile cases of misuse of lethal force, dangerous vehicle pursuits, or fatal neglect happen amid an everyday backdrop of cruel, dehumanizing, and even racist conduct. CBP and Border Patrol personnel routinely use physical violence, including with women and children, without a self-defense justification. They regularly intimidate migrants with abusive, even racist or sexist, language. They deport and expel people under conditions that they know to be dangerous. They separate families. They confiscate and fail to return important documents and valued belongings. They refuse food, water, and medical assistance. They falsify documents. They commit racial profiling. They sexually harass migrants, and their own colleagues. They violate privacy and civil liberties, and they espouse politicized and insubordinate views.

Not all Border Patrol agents and CBP officers behave in these ways. It’s most likely that a majority do not. But it is too uncommon to hear of “good” agents daring to speak up when they witness their colleagues committing the kind of acts that our organizations are able to document so frequently.

Examples of border law enforcement personnel being held accountable for these abuses, meanwhile, are vanishingly rare. The lack of accountability is so widespread that it helps cement in place a culture that enables human rights violations. The abuses keep coming because impunity is so likely.

This is why it is so crucial that mechanisms exist to hold rights abusers accountable. U.S. law governing foreign assistance allows aid to flow to another country’s police or military unit with a troubled human rights record, only if the recipient country “is taking effective steps to bring the responsible members of the security forces unit to justice.” Similarly, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) has a system in place that exists to take these “effective steps.” This system, however, needs an overhaul.

This report is divided into three sections.

Section I cites recent examples of alleged CBP and Border Patrol abuses that have come to light through one of two accountability pathways – either through the agencies initiating investigations on their own, or through an outside party uncovering the abuse and initiating a complaint.

Section I notes the severity of the crimes and abuses investigated on the first pathway. Because our organizations track abuse and pursue complaints, we mainly focus on the second pathway. In our experience, while neither pathway leads very often to justice, it is very rare to see an outside complaint result in either a disciplinary measure or a policy change.

Section II explains how the DHS accountability system is meant to work. Four accountability offices, with overlapping responsibilities, now exist within DHS and CBP to investigate abuse allegations. All four have separate complaint intake forms and procedures. Cases can get passed back and forth between agencies and responses, if at all, come slowly. Only some agencies can enforce discipline or ensure that their recommendations are enacted. All face personnel and other resource inadequacies.

Section III explores why complaints so often fail to lead to justice. It lays out several of the most frequent “failure points” in DHS’s and CBP’s accountability system.

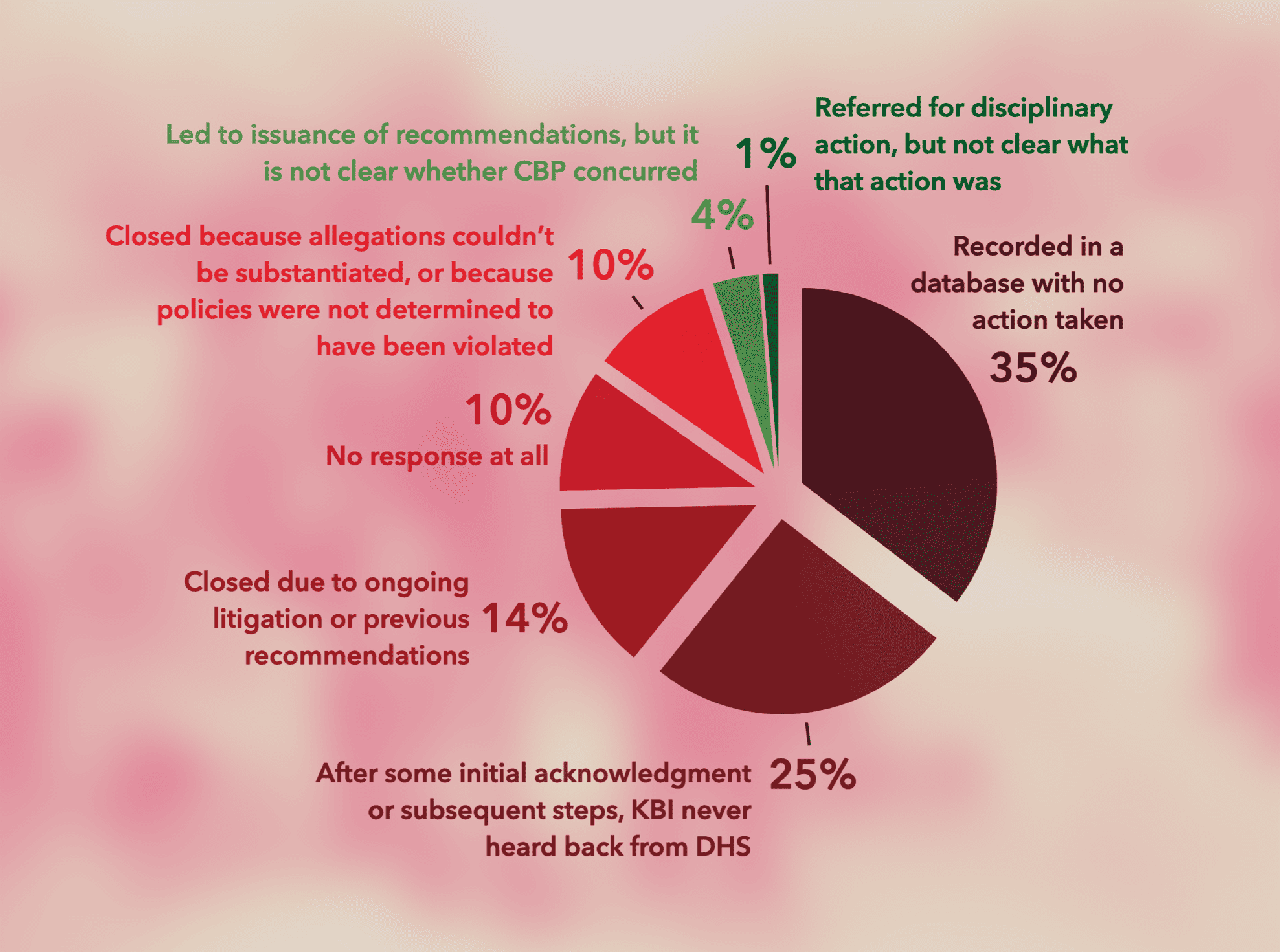

Of 78 complaints that KBI filed between 2020 and 2022:

Overall, 95 percent of the complaints KBI filed resulted in no accountability outcome at all. That is to say: they led to no proper investigation or disciplinary action. Only 5 percent led to either policy recommendations or discipline recommended for the agent in question.

(percentages do not total 100 due to rounding)

(percentages do not total 100 due to rounding)

Section III includes vivid examples from KBI’s complaints narrating each of these “failure points.” Some of the cases are egregious, and the victims must be bewildered by the absence of even a formal acknowledgement that what was done to them was wrong.

Section IV of this report offers more than 40 recommendations pointing the way toward the more effective and credible accountability system that is so urgently needed to improve U.S. federal border law enforcement agencies’ abysmal human rights record.

Some of these recommendations are technical, seeking to streamline unnecessarily cumbersome procedures. Some are budgetary, focused on addressing resource shortfalls. Some demand culture change, personnel changes, and a fundamentally different approach to oversight. Most would require little or no legislation from the deadlocked 118th Congress. Our organizations believe that such changes—well beyond a mere rearranging of organizational charts—are warranted by the severity of the abuses we continue to document.

We recommend significant changes:

Changing an abusive culture, and increasing the probability of accountability, can take many years and will face political headwinds. But as the many, often shocking, abuses documented in this report make plain, there is no other choice. The United States must bring its border law enforcement agencies’ day-to-day behavior back into alignment with its professed values.

Public trust in U.S. border governance requires it to be rights-respecting and consistently professional. It should be a model that the rest of the Western Hemisphere could learn from at a time of historic migration. And when it is not, it must have the means to take effective steps to hold its personnel accountable.

WOLA and KBI hope this report helps to move U.S. border governance toward this outcome.

This report was made possible, and tremendously improved, by editing, design, research, communications, and content contributions from Kathy Gille, Joanna Williams, Ana Lucía Verduzco, Zaida Márquez, Sergio Ortiz Borbolla, Milli Legrain, and Felipe Puerta Cuartas. We could not do this work without the generosity of our supporters; please become one of them.