Photo: Kino Border Initiative; Illustration: Sergio Ortiz Borbolla

Photo: Kino Border Initiative; Illustration: Sergio Ortiz Borbolla

WOLA and the Kino Border Initiative have documented many examples of abusive or improper conduct committed by U.S. border authorities. We have also identified glaring flaws in the accountability process at the Department of Homeland Security.

We present this extensive report in several sections. Section I covered the scope of the abuse problem and the need for accountability. Section II explained how the accountability system is meant to work. Section III looked at why the system so often fails to achieve accountability.

Here in Section IV, we issue a series of more than 40 recommendations for improvements to the complaints system, abuse investigations, personnel discipline, congressional oversight, and organizational culture change.

This report documented a chronic problem of human rights abuse within the U.S. federal government’s border law enforcement agencies. Curbing this problem requires increasing accountability for abuse when it happens. If the probability of discipline increases, behavior that is abusive and contrary to good border governance will decline. If the probability of redress increases, victims will be more willing to come forward.

IV.A. Making the complaints process work

Accountability requires careful oversight, and a large component of that is the ability to receive, process, and adjudicate complaints as quickly and efficiently as possible. That ability is lacking, as this report amply demonstrates, and as KBI has documented in reports and letters since 2017.

The complaints process is too complex, with overlapping responsibilities and opaque procedures. Advocates often try to make complaints to various accountability offices due to their overlapping jurisdictions. Even so, there are remarkably few examples of victims who, after submitting a complaint, have achieved a result that restores the harm done and upholds their dignity. In too many cases, they receive no response at all.

To improve the complaints process, particularly at CRCL, our organizations offer 10 recommendations.

Advocates and others filing complaints lack clarity on how to do so in a way that ensures that the appropriate oversight agency receives them. For instance, a 2012 DHS document, “How to File a Complaint with the DHS,” explains, “As an alternative to reporting a complaint to the DHS Office of Inspector General (OIG), complaints involving CBP or Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) employees can be sent to the Joint Intake Center.” [25] The document, however, does not explain why doing so would be appropriate or what would be the advantage of taking this route.

The DHS document also names CRCL as an appropriate agency to reach out to in the event of “physical abuse or any other type of abuse.” However, an official from another oversight agency interviewed for this report said that CRCL is most appropriate for “macro” problems and not for individual complaints that need quick resolution. This official suggested that advocates should send complaints that represent a long-standing pattern of abuse to CRCL and send complaints that need an immediate and individual solution to OPR.

However, nearly every abuse that advocates see requires an individualized solution while also forming part of a long-standing pattern of abuse. Oversight agencies must improve the complaint intake process so that agencies can simultaneously redress individual complaints and analyze patterns of abuse.

After years of advocacy in this arena, KBI has learned that the most effective way to file a complaint is to send an email “CC”-ing the intake emails of all oversight agencies that could possibly be involved in investigating the complaint. A senior DHS official acknowledged, “‘Go to everybody’—that’s still the best answer. I’d rather get it in more places than not, and we might have different parts of the pie.” [26] However, an individual complainant seeking redress for an abuse would have no way to know that.

Also, even when KBI sends copies to the JIC and OPR in addition to CRCL, many complaints go unanswered. Most recently, OIDO responded to a complaint KBI sent to CRCL and copied OIDO, requesting that KBI fill out OIDO’s separate case form. Generally, it is only when KBI leverages its staff’s personal contacts and the interest of specific investigating agents who care about improving oversight, particularly within OPR, that KBI has received a more timely and individualized response.

CRCL recently created an online portal to submit complaints. It uses the same format as the agency’s PDF complaint document, so it is unclear how the portal will improve the current process for complainants or CRCL staff.

Given the overlapping responsibilities of the accountability offices, KBI has found it beneficial to send complaints to all of the offices that could potentially investigate the allegations. However, each office has its own portal and complaint format, and one office may not accept a complaint formatted for another. Merely getting the complaint to the correct office, so that it might take action, requires migrants and advocates to spend hours reformatting and re-submitting complaints to different agencies.

The four agencies should work together to create a single common intake form that would solicit the information necessary for any office to open an investigation. This shifts the burden away from survivors and their advocates. A more streamlined complaints process could encourage more NGOs to take the time to file complaints, beneficial to survivors and accountability offices alike.

It should be easy for complainants and their advocates to know the most recent step that agencies have taken to act on their complaints and to hold personnel accountable. Even a phone call should be unnecessary. The four agencies should maintain online, password-protected, regularly updated resources (or, ideally, one DHS-wide resource that combines information from all four) that make clear the most recent “accountability step” taken in each case.

Complainants or advocates would create online identities with unique passwords. Upon logging in, they would be able to view the most recent status of each of their complaints. Just as someone tracking a package for a purchase can see whether it is “shipped,” “in transit,” or “out for delivery,” someone tracking their complaint should be able to see whether it is “shared with OIG,” “under local law enforcement investigation,” “under OPR investigation,” “recommendations issued,” “case closed,” or similar.

Some officials interviewed for this report conveyed that CRCL, CBP OPR, and DHS OIG have difficulty processing what they called “hybrid complaints”: letters or other documents that narrate more than a few abuses all at once, and that may combine different categories of abuses. CRCL stated that such complaints can be useful for identifying systemic problems, but that may not be satisfactory for a victim seeking redress for a specific case. When attorneys or advocates send what an official called a “giant letter,” agencies appear to get paralyzed, unable to decide how to break apart the cases presented and which agencies should pursue them. Often, as a result, nothing happens.

The general inability to process “hybrid complaints” is not the fault of the complainants or the organizations advocating for them. Often, organizations are made aware of so many cases that presenting each as separately filed complaints is either impractical or would divorce the alleged abuse from the larger context in which it is happening. (An example would be four legal aid organizations’ joint complaint about abuses of unaccompanied children in CBP custody in 2021, which lists several dozen separate abuses that could have led to a flood of complaints. [27])

This problem can be addressed by having the agencies set up an internal process to “break apart” hybrid complaints on their own, dividing each into individual cases as necessary, and ideally in coordination with the complainant. That process should also have clear ground rules for quickly deciding which agency should follow up on each case.

It can also be solved by having agencies communicate more clearly to the public the format of complaint that works best for this process. Even without this process, it is incumbent on CRCL and other agencies, as soon as possible, to provide clearer public guidance regarding characteristics of complaints that would increase the likelihood of speedier consideration.

The 2016 Final Report of the CBP Integrity Advisory Panel recommended that CBP “acknowledge all complaints received from the public.” [28] All agencies must provide an initial response, acknowledging receipt of complaints, 100 percent of the time.

CRCL officials state that they aim to get a written response to a complainant within 30 days. KBI’s experience, documented above, shows that this does not happen systematically.

The complainant should know whom to contact to discuss their case, with a direct phone number or extension and e-mail address. Given the lamentably high staff turnover rate that some of these agencies suffer, it is critical that the point of contact’s replacement reach out to complainants upon taking over, and automatically receive all emails and calls related to the case without the complainant needing to take action.

When CRCL resolves a complaint or series of related complaints, it sometimes issues recommendations to the relevant DHS agency. CRCL usually publishes redacted recommendations online in its Library of Recommendations and Investigation Memos. (DHS officials interviewed made clear that CRCL is not the redactor of its reports on recommendations: “to the extent that we can share, we share.” [29]) CRCL also submits an annual report to Congress, in which it outlines in general terms its recommendations issued over the past year, though this report is usually issued more than a year after the fiscal year it covers has ended.

However, CRCL has routinely failed to make complainants aware that their complaints have contributed to recommendations. “People who have filed complaints with the Office don’t receive a readout of what those recommendations were, or what the findings of their investigation were,” Shaw Drake, then of ACLU Texas, said at an October 2022 WOLA event. “Those recommendations, unlike Inspector General reports, are not made public. It’s even harder to follow up on those to force the agency to adopt them or to even pressure them into commenting on why they have or haven’t.” [30]

In complaint closure letters, CRCL often cites that it has previously “emitted recommendations” related to the complaint at hand and therefore is closing it. However, closure letters do not provide a name for the recommendations, a hyperlink, or any direct way to find them. CRCL closes complaints related to recommendations emitted in the past, considering that due diligence has already been performed.

CRCL staff confirmed that they do not send the recommendations to the complainant whose allegations started the investigation. This is because negotiations with the DHS agency that receives the recommendations are deliberative and may be ongoing, so CRCL does not share recommendations until it has a final agency decision.

In contrast, CRCL’s authority, under Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, to investigate and provide remedy for disability discrimination complaints among DHS employees has much higher standards: if CRCL receives a complete complaint, it is required to investigate it, issue a determination letter within 180 days, remedy the complaint and share this remedy in detail with the complainant regardless of whether the agency concurs with the findings.

Where allegations of abuse by border law enforcement agencies are concerned, there is currently no way to know whether the agencies receiving CRCL’s recommendations have concurred with them or not. In redacted recommendations CRCL has published on its website, the recommendations clearly state: “We request that [DHS agency] provide a response to CRCL in 60 days whether it concurs or non-concurs with these recommendations. If you concur, please include an action plan.” However, there is no published record of the agency’s response or action plan. CRCL has no enforcement power, yet it is charged with “monitoring” the implementation of its recommendations.

It is concerning that CRCL closes incoming complaints related to issues about which it has previously created recommendations, without being able to enforce or effectively monitor these recommendations, even as the DHS agencies continue to commit the same abuses. CRCL staff confirmed that they have limited options when the DHS agency does not concur, sharing that if they continue to receive new complaints regarding the same issue, they must attempt to open a new investigation and issue new recommendations if the complaints show something novel that the original investigation might have missed.

Informing complainants about the outcomes of investigations and recommendations is critical to the credibility of the entire process. In 2014 the ACLU and the Women’s Refugee Commission recommended that DHS “provide complainants a summary regarding the outcome of their complaint within one year, including findings of fact, findings of law, action taken, and available redress.” [31] The CBP Integrity Advisory Panel recommended that CBP “notify complainants by letter of the results of such complaints, including administrative or disciplinary action, if any, to the extent permitted by law and legitimate privacy concerns.” [32] The recommendations of both of these groups remain relevant and important.

CRCL needs an internal system that can flag a “pattern of abuse” investigation when it receives a certain number of complaints about the same type of abuse (or “primary allegation,” as CRCL reporting refers to it).

The majority of closure letters from CRCL cite that the complaint has been recorded in the agency’s “information layer.” As the situation currently stands, it is not clear what amount or severity of built-up complaints triggers the agency to initiate a pattern of abuse investigation. CRCL staff have only referred to a “tipping point” that would potentially lead to an investigation of a recurring issue.

An added challenge emerges in cases where CRCL previously investigated and emitted recommendations to an agency, but related complaints continue, potentially due to the agency’s non-concurrence with the recommendations. It appears that CRCL cannot open a new investigation unless the new complaints contain novel information that was not included in the original investigation. This means there may be no redress for patterns of abuse that continue even after an investigation concludes with recommendations to make changes.

It is necessary that CRCL release transparent information about what standards the Office uses to decide when a pattern exists in the information layer, and when that pattern would trigger an investigation and policy recommendations. “We know it when we see it” is not enough: an objective standard should exist that requires CRCL to open an investigation once it has received a certain number and severity of related complaints. Further, CRCL should release transparent information about how it escalates patterns of abuse if they continue to occur even after investigations and recommendations.

“In 2019,” the Project on Government Oversight (POGO) observed, “DHS committed to ‘developing a case tracking system that will track disciplinary and adverse actions across all components and will develop a reporting process to capture, manage, and monitor components’ management of discipline and adverse action [by] March 31, 2022.” [33]

This is a solid recommendation—but that date has passed, and no such tracking system exists, at least not in any format available to complainants. The passing of complaints and cases between CRCL, OPR, and OIG continues (as discussed in recommendation 2a below), in a manner so opaque that complainants have little way of knowing which agency may be “holding” their case at any given moment. Adopting the online, password-protected resource proposed in recommendation 1c above could alleviate this.

An individual or organization informed that their case will receive no further consideration deserves an explanation why CRCL opted to take no further action beyond noting it in its database. This is especially important when the complaint involves physical abuse.

Whether an external organization enters a complaint, or whether a case originates at DHS investigators’ initiative, the quadripartite model of CBP oversight—with CRCL, OPR, OIDO, and OIG sharing overlapping responsibilities—is confusing and often frustrating for all involved.

A lack of clarity about responsibilities, a lack of transparency about cases’ progress, a lack of clear timeframes for action, and a lack of resources combine in a way that can benefit those who commit offenses. These factors also serve as convenient pretexts for inaction when political will for more energetic oversight is weak.

As noted in Section II above, the DHS OIG has the “right of first refusal” for taking on complaints issued to CRCL. CBP OPR must also send to the OIG all cases of “serious allegations”: allegations of misconduct serious enough to merit at least a two-week suspension. [34] “Right of first refusal” means that, in these cases, CRCL and OPR cannot move ahead on their investigations until the OIG notifies them that it will not take on the case.

As Section II explains, if the OIG decides not to investigate a case, Management Directive 810.1 gives it five business days to notify the DHS agency that forwarded the complaint of that decision and return the complaint. There is no time limit, however, for OIG to make that decision about whether to take on a case.

While DHS officials claim that decisions often come quickly, lags are common. At present, whether the agency awaiting the OIG’s decision is OPR or CRCL, delays are frequent. At times, OPR personnel must proactively contact the OIG in order to shake loose its decision about whether to proceed on a case. Changes to the management directive would reduce these delays, especially if these changes make clear that OIG’s refusal to promptly hand off to other agencies in serious cases should be a rare exception, not the norm.

Waiting for the OIG’s decision can cause investigations to become needlessly delayed. It can take OIG “a month to open their mail,” one DHS official remarked. By then, many cases are likely to have gone cold.

This is unacceptable: at least in cases of serious misconduct, corruption, or use of force, Management Directive 810.1 must be amended to give OIG a time limit—which should be measured in days or a small number of weeks—within which to decide whether it will proceed with an investigation. Should that time limit expire, the case should immediately and automatically revert back to the relevant accountability agency, OPR or CRCL, so that it may take on the investigation as expeditiously as possible.

This requires, at least in part, completing an overdue revision of the 2004 management directive. In its 2015 interim report, the CBP Integrity Advisory Panel issued a de-confliction recommendation that remains relevant and urgent, eight years later. Recommendation 4 called on CBP to work with DHS to amend a 2004 Management Directive (810.1) so that the OIG would “ordinarily defer” to OPR when allegations involve corruption, misuse of force, and other serious misconduct allegations. Currently, such cases go immediately to OIG, which risks delaying investigation, “unless failure to do so would pose an imminent threat to human life, health or safety, or result in the irretrievable loss or destruction of critical evidence or witness testimony.”

Should the OIG refuse to defer in a case, the Integrity Advisory Panel proposed that “the default position” should be that personnel from the OIG and OPR investigate jointly. Finally, the panel recommended: “In any event, it should be clarified that the commencement of an investigation by IA [now OPR] will not be delayed while OIG is evaluating whether to take an investigation.” [35]

In their explanatory statement on the 2022 Homeland Security Appropriations law, issued on March 9, 2022, congressional appropriators gave DHS six months to issue a revised version of Management Directive 810.1, in which the OIG’s “jurisdiction shall be reviewed to ensure it is narrowly tailored to ensure that the Department’s other oversight functions [CRCL and OPR] are able to continue to execute their responsibilities.” [36] As our organizations publish this report in July 2023, the congressional deadline is now ten months past, and DHS has produced no new directive.

While the CBP Integrity Panel’s recommendations dealt with jurisdictional overlaps between the OIG and CBP OPR on cases like corruption or use of force, similar questions persist between the OIG and CRCL when a case involves a civil rights violation. Here, more than a DHS directive might be needed to clear things up: the issue lies with the law as currently drafted.

A recent enhancement to the Inspector General Act of 1978 (Section 417 of Title 5 U.S. Code) gives the DHS OIG a greater role in investigating violations of civil rights and civil liberties. While stronger civil rights investigations are welcome, the change makes it less clear which agency—OIG or CRCL—is ultimately responsible for civil rights cases. To further confuse matters, OPR may claim jurisdiction if the civil rights violation is a criminal matter. Congress must disentangle this snarl of statutory authorities.

The point presented in recommendation IV.A.4. above is also relevant to cases of jurisdictional overlap. If an external complainant submits a document laying out several cases, and if the cases presented appear to fit within different accountability agencies’ jurisdictions, the result must not be inaction. The agencies need to develop a clear process for assigning responsibilities raised by “hybrid complaints,” as victim-survivors and their advocates are very likely to keep submitting complaints in this format.

Of the most serious investigations, for instance, those involving physical abuse and use of force, the preponderance of cases goes before CBP OPR. In such cases, OPR faces the difficult but indispensable demand to investigate all misconduct allegations both quickly and thoroughly. We offer four key recommendations here.

Particularly when under pressure to add personnel quickly, OPR may end up hiring career Border Patrol agents or CBP officers. Agents and officers may be more likely to understand patterns of behavior surrounding abuses and the operational contexts in which they occur. However, agents and officers are also more likely to be imbued with these agencies’ organizational culture, which has favored impunity for some of the very troubling abuses and behaviors described in this report’s first section.

Many agents and officers surely reject this culture and wish to work within OPR to change it. Those in charge of increasing OPR’s staffing must take great care to review backgrounds and references to ensure that any new hires from within CBP truly fit this description.

Our organizations underscore a recommendation made by POGO in 2021: “Congress should audit the backgrounds of investigators at CBP, who are often former officers or agents, and examine whether the proportion of such investigators aligns with law enforcement best practices.” [37]

This is doubly true in the case of former members of Border Patrol’s notorious Critical Incident Teams (CITs), an internal structure that CBP terminated in 2022 amid allegations that the teams hindered investigations and worked to exonerate agents who may have committed wrongdoing. With that background, the probability is high that former CIT personnel might be insufficiently aggressive in reducing impunity. Following the CITs’ dissolution, it is troubling that, as the Southern Border Communities Coalition has noted, OPR is hiring the former teams’ members. [38] Any candidates for OPR investigator positions who have CIT experience deserve extreme scrutiny to overcome a presumption of ineligibility.

Hiring from outside CBP, or even DHS, carries other advantages. Individuals who have worked elsewhere in government, or the private and nonprofit sectors, come from different organizational cultures and bring fresh perspectives and best practices that accountability agencies could do well to adopt. A greater diversity of hires helps avoid “groupthink” and the tendency to perpetuate inefficiencies “because we’ve always done it this way.”

“The Office of Professional Responsibility was granted in 2016, by legislation, the authority to be federal criminal investigators. Along with that came a number of requirements that the office is still not in compliance with,” Shaw Drake, then of ACLU Texas, explained at an October 2022 WOLA discussion. “One of them is something called feedback. So they’re required to give feedback to complainants stemming from that legislation, and they still don’t have policies on the books to do that. But they have committed to us and to other organizations that they intend to institute policies that better provide feedback to complainants about the outcome of their investigations.” [39]

In line with this report’s recommendation (IV.A.2) that DHS maintain a website where the public can see the last accountability action taken in a case, our organizations echo and emphasize Drake’s call on OPR to complete and begin implementing its policy on feedback to complainants. As Drake explained, this would create “a system whereby in the future, complaints that are filed with OPR get at least some indication of how they were investigated, what the investigation found, what outcomes came from those investigations.”

A common problem with accountability agencies’ investigations is a frequent failure to interview or consult with victims, in some cases including victims of serious misuse of force. Often, non-citizen victims are removed from the United States without ever talking to an investigator.

KBI has received multiple closure letters stating that the complainant’s allegations could not be substantiated, explaining that the investigation consisted of talking with the CBP agents, reviewing CBP policy, etc., with no mention of interviewing the impacted person or even having attempted to do so. It is concerning if oversight agencies only interview the federal law enforcement agencies accused of these abuses without also talking to the impacted person, interviewing other witnesses who are not government employees, reviewing camera footage when it exists, and taking other steps to ensure a balanced investigation.

If a non-citizen victim files a complaint with CRCL, OPR, OIG, or OIDO, that individual should not be removed from the country without first being interviewed by an investigator. If they are removed, the investigator must show that they have made a good-faith effort, including overseas travel if necessary, to contact and interview the victim who issued the complaint.

Contact with victims—whether in-country or removed—should happen in a timely manner. When agencies delay initial action on a complaint, losing valuable weeks or months, the likelihood of victims being unreachable increases.

Footage from body-worn and dashboard cameras makes OPR investigators’ work much more effective. Rapid deployment of this equipment must be an utmost priority. CBP’s August 2021 publication of a directive governing this technology’s use was an important step. [40] So is the public sharing of body-worn camera footage on three occasions, between April and June 2023, on CBP’s Accountability and Transparency web page. [41]

In its May 23, 2023 announcement of a new department-wide body-worn camera policy, DHS revealed that CBP has distributed 7,000 cameras to its workforce since the August 2021 publication of an agency directive. [42] The Biden administration’s 2024 Homeland Security budget request includes $19.6 million to fund “the expansion to 4,275 additional body-worn cameras” for CBP’s Office of Field Operations officers. [43]

As discussed above, the DHS OIG has the “right of first refusal” on whether to investigate most complaints and cases, whether they originate from within the agency or from outside complainants. This agency plays a crucial role in overseeing the U.S. government’s largest civilian law enforcement agencies, but it is in a poor state of health.

A June 2021 Government Accountability Office report found “long-standing management weaknesses” at DHS OIG, including “work quality concerns, high leadership turnover,” operating without a strategic plan, and a steadily increasing amount of time taken to complete reports. [44] In all of fiscal year 2022, the OIG completed just 11 reports overseeing CBP’s U.S.-Mexico border mission. [45]

The OIG’s “reports include recommendations to the agency [like CBP],” ACLU’s Drake explained, “but of course, the agency is under no obligation to institute any of those recommendations and oftentimes disputes the findings and provides comments on their opinion about the recommendations, but there’s really no ability to force them” to adopt the recommendations and make changes. [46]

The appendices of the OIG’s semi-annual reports to Congress list hundreds of open recommendations from past reports, many of them issued to CBP. This is a problem: when there is no consequence for ignoring a recommendation, harmful behaviors and practices are much more likely to persist. The OIG needs the ability to attach sanctions to recommendations that remain open or unresolved for too long, and the will to do so.

Since his mid-2019 confirmation, DHS Inspector General Joseph Cuffari has served an embattled tenure. “Cuffari’s three years as Homeland Security’s inspector general have been marked by numerous allegations of partisan decision-making and investigative failures—including, most recently, his decision in February to scrap efforts by his department to recover Secret Service texts sent during the Jan. 6 insurrection,” the Washington Post reported in August 2022. [47]

Since 2019, the majority of lawyers in the OIG’s Office of Counsel have left, creating “a revolving door that has hindered oversight of DHS,” NPR reported. [48] As discussed above, POGO revealed that Cuffari’s office stifled internal personnel surveys pointing to widespread sexual harassment and toleration of domestic abusers in law enforcement positions. [49] In 2022, anonymous OIG employees “representing every program office at every grade level” drafted a blistering letter calling for Cuffari’s removal. [50] The Inspector General’s Ph.D. has even been called into question. [51]

Its role in guaranteeing Americans’ security, and the troubling frequency of human rights abuses, make DHS too important to be overseen in such a stormy, disorderly manner. Out of respect for the autonomy of inspectors-general, President Biden has refused to remove Joseph Cuffari. Our organizations join POGO’s repeated calls on the President to make an exception in his case. [52]

The frequency with which punishments are overruled or actions found to be within CBP’s use of force policy is incongruent with the often severe abuses that this report’s first section documents. It points to levels of impunity for human rights abuse similar to those found among the militaries and police forces of Latin American nations where WOLA engages with partners defending rights and democracy.

In 2014, DHS delegated to CBP the authority to investigate its own employees for alleged criminal misconduct, a step billed as “part of a larger effort to hold the workforce accountable.” [53] U.S. law (Title 6, Section 211(j), U.S. Code) empowers OPR to “investigate criminal and administrative matters and misconduct.”

It is rare for a law enforcement agency to have the power to investigate its own personnel for criminal matters. This may be part of the reason why it has proven impossible to convict a CBP employee for a human rights abuse committed on duty, no matter how serious.

The track record calls at least for carving out this self-investigation power in cases of human rights abuse. This, however, would require a statutory change that the current (118th) U.S. Congress is unlikely to take up.

Barring that, our organizations recommend that the Department of Justice play a clearer role when CBP personnel commit what could be criminal abuses. One means of doing that would be to assign a special U.S. assistant attorney to CBP to carry out internal criminal investigations and prosecutions. This official should be independent in form and function, with no prior background as an employee of the agency.

When OPR does not refer a case for criminal prosecution, and instead recommends administrative disciplinary measures, the process of meting out an actual punishment is convoluted and untransparent.

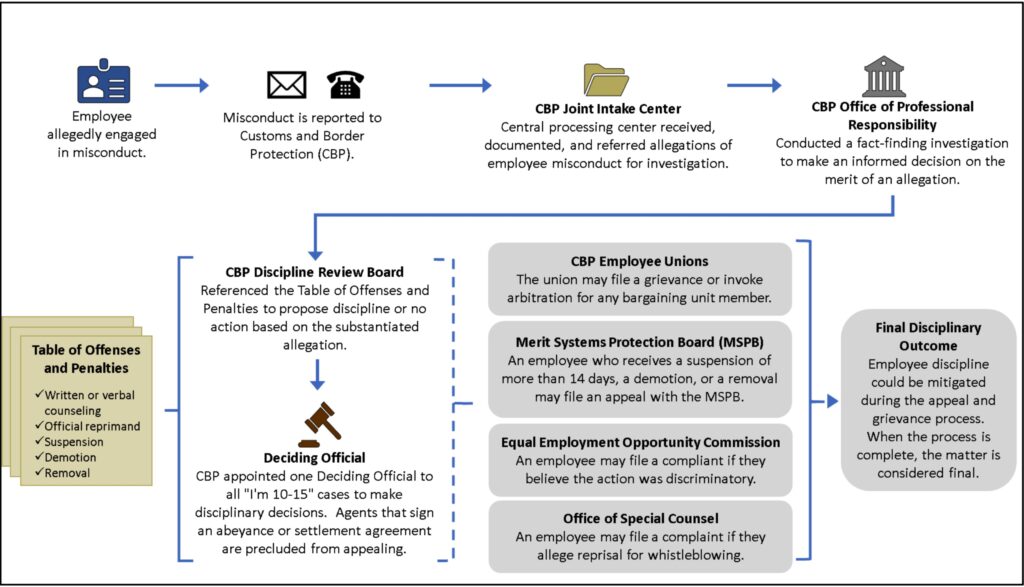

Disciplinary decisions’ circuitous route

Source: U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Oversight and Accountability Democrats, September 14, 2021: https://oversightdemocrats.house.gov/cbp-report

Source: U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Oversight and Accountability Democrats, September 14, 2021: https://oversightdemocrats.house.gov/cbp-report

Page 6 of the House Oversight Committee’s report on the Border Patrol Facebook group included a graphic showing the circuitous process that an investigation takes, from CBP’s Joint Intake Center, to OPR, to CBP’s Discipline Review Board and an appointed “deciding official.” That official is usually within the accused agents’ chain of command. OPR effectively “cedes authority over investigations to the human resources component” of CBP, as POGO put it in a 2021 report. [54]

Whatever punishment those bodies recommend may then be appealed:

A large share of recommended punishments were appealed in the case of the Facebook scandal, most often through union grievances. As a result, “Of the 58 agents that CBP found to have committed misconduct but did not remove from their positions, 57 continue to work in positions of power over migrants, including families with children.” [55]

Of the disciplinary system, a DHS official told us, “There is a problem here, reforms were promised, we’re all waiting to see what the reforms are.” [56] This official was referring to DHS Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas’s June 16, 2022 order for the Department to reform its employee misconduct discipline processes, based on the unpublished results of an earlier 45-day review. [57]

“I have directed the Department to implement significant reforms to our employee misconduct discipline processes,” the Secretary stated, “including centralizing the decision-making process for disciplinary actions and overhauling agency policies regarding disciplinary penalties.”

To date, if such changes have begun implementation, there is no public disclosure. These necessary reforms are still pending.

This recommendation amplifies one issued in 2016 by the CBP Integrity Advisory Panel:

Give the Commissioner the authority, similar to that of the Federal Bureau of Investigation Director, to summarily suspend without pay and/or terminate law enforcement employees of CBP who have committed egregious, serious and flagrant misconduct, such as, accepting bribes in exchange for being influenced in their official duties. [58]

Often, the “deciding official” on discipline review cases is the leadership of the Border Patrol sector where the agent facing allegations is employed. This, ACLU’s Drake explained, means “that the supervisors and bosses of the individual agent who has done something wrong get a chance to make their own decisions about what discipline is sought against the agent. Of course, there’s a conflict of interest there, because no supervisor looks good when their agents below them are being doled out extensive disciplinary measures.” [59]

“This system leads to localized discrepancies in discipline and an incentive to protect colleagues in the field,” POGO’s 2021 report explained. “Indeed, many complaints are not even elevated to headquarters, but rather retained locally through an opaque determination that the alleged misconduct is not serious enough to be reported to CBP’s central complaint processing entity, the Joint Intake Center.” [60]

It is abundantly evident how this system sets up incentives and leads to outcomes that create strong obstacles to accountability for abuse and misconduct. This system should not be adjusted: it should be scrapped entirely. Those in an agent’s chain of command should not have a role in determining discipline.

One reason that so many use of force cases are found to be “within policy” is that CBP’s use of force policy employs a “reasonableness” standard to determine whether a use of force, including deadly force, was justified.

The CBP use of force policy explains that a law enforcement officer (LEO) may use force when the officer “has a reasonable belief that the subject of such force poses an imminent threat of death or serious bodily injury to the LEO or to another person.” [61] A migrant picking up a rock or making a sudden move could be interpreted as “reasonably” justifying a disproportionate use of force, like firing a weapon—and the case could be dismissed as “within policy.”

As the Southern Border Communities Coalition has explained, internationally recognized law enforcement standards now go beyond “reasonableness.” [62] The 1979 UN Code of Conduct for Law Enforcement Officials applies a standard of “necessary and proportionate” to govern law enforcement’s use of force. [63] That means that the decision to use force not only must be deemed necessary, but the force used was matched to the perceived threat. Many of the cases described in this report’s first section do not appear to describe responses that were “proportionate.”

Any board that can fully exonerate 96 percent of use of force cases deserves much closer scrutiny, because it is not increasing the probability of being held accountable, and thus not likely to be affecting agents’ behavior.

These case outcomes point to likely dysfunction in the National and Local Use of Force Review Boards. What that dysfunction is falls outside the scope of this report, as the preponderance of serious use of force cases take what we have called the “first accountability pathway” of authorities investigating on their own initiative. Still, our organizations note that these boards urgently require energetic scrutiny, with an eye toward diagnosing necessary reforms.

Union grievance arbitration and Merit Systems Protection Board appeals are meant to defend workers from abusive or arbitrary management practices. Seeking accountability for a human rights abuse is emphatically not an abusive or arbitrary management practice.

The presumption, in cases of alleged human rights abuses, should be that the disciplinary decision is not a labor matter. To portray it as such, the accused should have to meet a high evidentiary standard before bringing it to appeals and arbitration.

In fact, our organizations uphold the 2016 recommendation of the CBP Integrity Advisory Panel for such cases:

Place CBP law enforcement personnel into Excepted Service in light of the critical national security mission of CBP’s Border Patrol Agents along our nation’s land borders and CBP Officers at our nation’s ports of entry. A law enforcement organization, such as CBP, is not benefitted, and the deterrent effect of discipline is substantially undermined, by lengthy post-discipline hearing processes of the Merit System Protection Board and collective bargaining agreement appeals to outside arbitrators. [64]

This recommendation of the Integrity Advisory Board has not been implemented.

Agencies like CRCL, OPR, OIG, and OIDO are not the only bodies empowered to guarantee transparency and accountability over federal border law enforcement agencies’ conduct. The U.S. Congress, in its constitutional oversight and appropriations roles, has a vital role to play as well, especially its committees on Homeland Security, the House Oversight and Accountability Committee; the Judiciary subcommittees on border security; and the Appropriations subcommittees on Homeland Security.

In recent years, Congress has increased funding for DHS’s oversight agencies and required CBP to produce more reports on investigations and discipline, which are valuable resources. These are important steps. However, despite the severity of the patterns of abuse documented in this report’s first section, congressional oversight bodies tend to prefer raising issues in private briefings and communications, rather than scrutinizing these agencies in public.

The House Oversight Committee’s October 2021 report on Border Patrol’s secret Facebook group was a very useful public resource, but it was unusual. [65] Such reports are scarce, as are hearings covering these issues, questions asked of officials at hearings, GAO reports, and other tools that could, by virtue of being public, make accountability and discipline a more central part of the public debate on border security and migration.

During the spring of 2023, congressional committees brought in U.S. officials—most often, DHS Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas—to testify about the situation at the U.S.-Mexico border and other challenges facing DHS. Some of these hearings have been highly partisan, focusing on shifting blame for recent increases in migration and fentanyl seizures.

Despite suggestions from a coalition of advocates, our organizations are not aware of a single legislator asking an official about CBP abuses or accountability during spring 2023’s cycle of politicized hearings. Hearings should be a strong forum for advancing oversight, voicing concerns, and obtaining new information about efforts to curb abuse and misconduct. But they have been a missed opportunity.

Congress has been quite tolerant of DHS’s chronic lateness in publishing and submitting reports required by law on abuses, discipline, and accountability. As a result, even for issues as serious as agent-involved fatalities, data aren’t provided until many months (or even years) after the end of the fiscal years in which events occurred.

Legislative oversight personnel need to prod DHS harder to produce delayed reports, even pausing obligations of funds if necessary. Once reports are produced, reporting that is vague, shoddy, or deliberately obfuscatory should trigger follow-up questions and demands for greater detail about abuses, investigations, and consequences. Responses to such questions, to the greatest extent practicable, must also be publicly available.

The Government Accountability Office, the U.S. Congress’s auditing arm, produced an important 2021 report about management weaknesses at the DHS OIG. Congress should ask the GAO to perform a larger evaluation of DHS’s larger quadripartite accountability and discipline arrangement, which—as discussed in much of this recommendation section so far—suffers from stark design flaws and implementation shortcomings.

When an important abuse complaint gets stuck or “disappears” within DHS’s accountability offices, complainants should be able to appeal for effective action from oversight personnel at relevant congressional committees. Our organizations uphold POGO’s 2021 recommendation that “Congress should assist NGOs in getting adequate responses to past-filed complaints and require oversight components to explain their lack of communication.” [66]

As this report shows, many abuses would never be brought to light if not for victim-survivors and advocates who dedicate time and energy to filling out complaint forms. Congress needs to help make this process more accessible.

Congressional staff should advocate for the immediate revision of Management Directive 810.1 and ask DHS to create a transparent de-confliction process. Further, congressional staff should request that DHS create accessible public-facing information explaining the jurisdiction of each accountability office and outline best practices for how to submit complaints.

CRCL’s Fiscal Year 2021 Annual Report to Congress calls the agency “an office of nearly 100 people in a Department with more than 240,000 employees.” [67] Further, only some CRCL staff work in the Compliance section, which investigates complaints. This would imply that CRCL lacks the personnel strength necessary to process complaints in a timely manner. A high ratio of cases per employee appears to be a reason why complaints fall through the cracks.

As noted in IV.A.7. above, the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 requires DHS CRCL to remedy complaints and respond to complainants within 180 days, in cases of disability discrimination among DHS employees. This timeframe—six months—is reasonable for investigation and redress from a sufficiently resourced agency. Victims of alleged abuse at the hands of CBP or Border Patrol personnel should receive similar treatment for their filed complaints.

That may require two acts of Congress: a change in CRCL’s authority calling for it to provide responses within a reasonable time limit, and sufficient appropriations to give the agency the personnel and other capacity needed to do so.

As noted above, CBP OPR faces the difficult but indispensable demand to investigate all misconduct allegations both quickly and thoroughly. As anyone who has ever managed a project knows, “quickly” and “thoroughly” doesn’t mean “inexpensively,” and adequate staffing is the greatest expense.

In 2015, the CBP Integrity Advisory Panel recommended that OPR have a personnel strength of “550 Full Time Equivalent (FTE) 1811 criminal investigators,” up from about 200 at the time. [68] Seven years later, in March 2022, the 2022 Homeland Security appropriation allocated sufficient funding ($74.3 million) to raise OPR’s staffing level to 550 criminal investigators and support staff. [69]

This funding, however, is available only until the end of fiscal year 2023 (September 30, 2023). This gave the agency 18 months to hire about 350 new investigators and support staff during one of the tightest job markets in modern U.S. history. [70] While it is important for OPR to act as assiduously as possible to reduce personnel gaps and caseloads, congressional appropriators must be flexible: unspent 2022 hiring funds must not expire in September 2023.

As of 2021, the DHS OIG had 773 staff positions, 701 of which were filled, 625 of them for program positions. [71] This is a surprisingly small number of personnel to perform in-depth oversight of CBP, ICE, Coast Guard, TSA, Secret Service, FEMA, Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), Office of Intelligence and Analysis, and smaller agencies, with a total personnel strength of 240,000. And of these, a significant majority of the 625 program positions are dedicated to audits and management reviews which, while important, do not address the dramatic human rights concerns that this report describes.

Without a significant increase, the OIG will continue to operate at a slow pace, unable to keep up with the fast tempo of new complaints and cases.

Despite the often heartbreaking gravity of abuses like those narrated in this report, accountability is often frustrated by an organizational culture at CBP and Border Patrol that fiercely opposes it. Especially in the case of Border Patrol, U.S. border law enforcement agencies’ “paramilitary” culture and expectation of impunity have been the subject of numerous books and articles. [72] As POGO observed in 2021, “What sets CBP apart—despite its police posture and quasi-military stance—is a deep-seated sense of exceptionalism and a tradition of evading even the meager oversight and accountability mechanisms that other law enforcement agencies are subject to.” [73]

Our organizations have no doubt that a strong majority of Border Patrol agents and CBP officers are law-abiding and would not themselves engage in cruel or abusive behavior. We note, though, that examples of such “good” agents speaking up about their colleagues’ “bad” actions appear to be vanishingly rare. This, along with a union that frequently works to oppose or water down discipline, contributes to a culture in which loyalty to the organization appears to outweigh loyalty to the rights-respecting principles that a democratic society demands.

Changing an organizational culture that is tolerant of abuse can take many years. Much of this change comes from increasing the probability that agents and officers will be held accountable, through the measures described above. Other changes have to do with the makeup of the agencies themselves.

The National Border Patrol Council (NBPC) is a union claiming to be “the exclusive representative of approximately 18,000 Border Patrol Agents and support personnel assigned to the U.S. Border Patrol.” [74] (Border Patrol had 19,306 agents as of the second quarter of fiscal year 2022. [75]) Like most unions, NBPC represents members in collective bargaining and in disputes over labor standards (overtime, benefits, and similar questions).

Like many law enforcement unions, NBPC also fiercely and vocally defends agents accused of human rights abuse, and—as noted in the “discipline” discussion above—frequently appeals disciplinary decisions in such cases. In its public messaging, NBPC often adopts extreme political positions, favoring restrictionist immigration policies, endorsing Donald Trump and other candidates promising to halt legal as well as illegal immigration, pre-judging asylum seekers as “scammers,” and even parroting the white supremacist “replacement theory” in public appearances. [76] The NBPC’s activities go well beyond defending its members’ labor conditions: it is now a principal pressure group for hardline border policies and for shielding members from accountability.

In January 2020, the Trump administration designated CBP a “security agency,” which means that employees’ names are no longer included in responses to Freedom of Information Act requests. This designation should have stripped the NBPC of its status as a union since federal law (Title 5 U.S. Code, Section 7112(b)(6)) holds that employees whose work “directly affects national security” may not be represented by a labor organization. [77]

Whether the NBPC should exist at all is beyond this report’s scope. However, given its precarious legal status, its high degree of politicization, and its contribution to a toxic organizational culture that weakens accountability, our organizations strongly recommend that the union play no role in cases involving allegations of human rights abuse, corruption, internal rights matters like sexual harassment, or any other type of misconduct for which the victims are members of the public.

As discussed in recommendation 2f, a draft, never-published report by the DHS OIG includes data from a survey of 28,000 of the Department’s employees. Of those respondents, 10,000—more than one-third—said that they experienced sexual misconduct on the job between 2012 and 2018. Only 22 percent formally reported it. “Among those who did report, a substantial number—about 41%—say doing so ‘negatively affected their careers,’” according to POGO, which revealed this survey’s existence in 2022, after OIG sat on the report for four years. [78] POGO also found that OIG heavily censored an earlier report revealing the extent of domestic violence committed by DHS law enforcement personnel.

The pervasiveness of sexual misconduct within DHS, and the lack of urgency with which the OIG approached the survey results, illustrate the toxicity of border law enforcement agencies’ organizational culture. If many employees themselves do not feel safe on the job—even to denounce sexual misconduct or harassment—then it is unsurprising that so many non-employees, both migrants and U.S. citizens, have negative experiences with CBP and Border Patrol.

Current and former employees have documented an inability to achieve redress for serious sexual harassment or assault allegations: it is a central subject of the 2022 memoir of former agent Jenn Budd. [79] Chris Magnus, who served as CBP’s commissioner from 2021 to 2022, told the New York Times that several women had described the agency’s sexual misconduct process to him “as pointless, especially when it involves complaining to a supervisor who may be close friends with the accused. ‘Too many of these guys just sort of stick together and protect each other,’ Mr. Magnus said. ‘It’s a culture of a wink and a nod.’” [80]

Changing this aspect of the agencies’ culture requires more determined movement against impunity. That in turn requires the OIG and OPR to act to curb such behavior, far more forcefully than they do now, and with backing from the highest levels.

Women who work for CBP must be able to demand, and receive, redress for on-the-job sexual harassment and abuse—including alerting law enforcement when laws are violated—without lighting their careers on fire. That so many women in the agency continue to view this as impossible is a searing indictment. The inaction of DHS accountability agencies and congressional oversight bodies is frankly shocking.

Women comprise an average of 15 percent of the workforce of federal law enforcement agencies. But not Border Patrol, where the share of women has remained at about 5 percent for years. [81] Cultural change requires more gender diversity within the workforce. Yet CBP continues to carry out most of its recruitment at events heavily attended by men, like rodeos and the April 2023 annual meetings of the National Rifle Association. [82]

Cultural reform and accountability depend on people within border law enforcement agencies being able to come forward with information about abuse, corruption, and misconduct without fear of retribution or seeing their careers derailed. As noted in the sexual harassment cases above, and as indicated by the lack of employees coming forward to denounce cases of human rights abuses, CBP’s whistleblower protections currently lack credibility. The agency has a long way to go before employees who witness or suffer wrongdoing will trust the process enough to engage in it.

According to current DHS policy, “CBP personnel may use race or ethnicity when a compelling governmental interest is present and its use is narrowly tailored to that interest. National security is per se a compelling interest.” [83] While the policy seeks to “tailor” the use of racial profiling, this represents an enormous loophole: a carve-out, upheld by Supreme Court rulings allowing profiling for “Hispanic appearance,” that applies to virtually no other U.S. law enforcement agencies. [84]

Our organizations echo POGO’s 2021 recommendation that the Department of Justice’s “2014 Guidance for Federal Law Enforcement Agencies Regarding the Use of Race, Ethnicity, Gender, National Origin, Religion, Sexual Orientation, or Gender Identity should be strengthened to close a glaring loophole that exempts law enforcement activity at the nation’s borders from this guidance.” [85]

Border Patrol agents frequently complain about being pulled away from law enforcement duties to process large numbers of arriving asylum-seeking migrants. Advocates for migrants’ rights, meanwhile, contend that Border Patrol agents are not trained to work with populations who, like asylum seekers, are trauma victims seeking to turn themselves in. KBI has documented numerous allegations of CBP and Border Patrol personnel abusing and disrespecting vulnerable people seeking to apply for asylum.

This points to a big and rare area of agreement between agents and advocates: armed, uniformed agents shouldn’t take the lead in processing asylum seekers. Our organizations recommend that processing—background, identity, and family relationship verification, health checks, initial asylum paperwork—be carried out by civilians trained to work with vulnerable, traumatized populations.

CBP’s hiring of about 1,100 Border Patrol “processing coordinators” to handle such tasks, along with plans to take on an additional 460 “processing assistants” at CBP and ICE in 2024, are steps in the right direction. [86] As nine years of large-scale protection-seeking migration make clear, the post of “processing coordinator” needs to become a permanent position with a professional career path, instead of a short-term contract.

An important processing change would remove CBP officers and Border Patrol agents from their current role in screening Mexican unaccompanied child migrants for protection concerns. Currently, agents are empowered to determine whether an unaccompanied child from a “contiguous” country might be in danger if returned. Few agents are trained to make this evaluation, and they may place Mexican children at serious risk of harm, as WOLA has documented. [87] Getting CBP personnel out of this determination would require Congress to adjust existing law (the 2008 William Wilberforce Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act).

[25] “How to File a Complaint with the Department of Homeland Security” (U.S. Department of Homeland Security, October 3, 2012), https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/dhs-complaint-avenues-guide_10-03-12_0.pdf.

[26] Senior DHS Officials, Interview with senior DHS officials, Microsoft Teams, April 21, 2023.

[27] Peter A Schey and Carlos Holguín, “Alleged Abuse of Unaccompanied Minors in Customs and Border Protection Custody” (Center for Human Rights and Constitutional Law, April 11, 2022), https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/21694269-alleged-abuse-of-unaccompanied-minors-in-customs-and-border-protection-custody.

[28] “Final Report of the CBP Integrity Advisory Panel” (Washington: Homeland Security Advisory Panel, March 15, 2016), https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/HSAC%20CBP%20IAP_Final%20Report_FINAL%20%28accessible%29_0.pdf.

[29] Senior DHS Officials, Interview with senior DHS officials.

[30] “Abuse, Accountability, and Organizational Culture at U.S. Border Law Enforcement Agencies” (Washington Office on Latin America, October 18, 2022), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zC84Vl67wLk.

[31] Jen Podkul and Neema Singh Giuliani, “Recommendations to DHS to Improve Complaint Processing” (ACLU, Women’s Refugee Commission, May 5, 2014), https://www.aclu.org/sites/default/files/assets/14_5_5_recommendations_to_dhs_to_improve_complaint_processing__final.pdf.

[32] “Final Report of the CBP Integrity Advisory Panel.”

[33] Sarah Turberville and Chris Rickerd, “An Oversight Agenda for Customs and Border Protection: America’s Largest, Least Accountable Law Enforcement Agency” (Washington: Project on Government Oversight, October 12, 2021), https://www.pogo.org/report/2021/10/an-oversight-agenda-for-customs-and-border-protection-americas-largest-least-accountable-law-enforcement-agency.

[34] Senior DHS Official, Interview with senior DHS official, Microsoft Teams, March 14, 2023.

[35] “Interim Report of the CBP Integrity Advisory Panel” (Washington: Homeland Security Advisory Panel, June 29, 2015), https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/DHS-HSAC-CBP-IAP-Interim-Report.pdf.

[36] “Congressional Record: Proceedings and Debates of the 117th Congress, Second Session” (U.S. Congress, March 9, 2022), https://www.congress.gov/117/crec/2022/03/09/168/42/CREC-2022-03-09-bk3.pdf.

[37] Turberville and Rickerd, “An Oversight Agenda for Customs and Border Protection.”

[38] Vicki B. Gaubeca and Andrea Guerrero, “New Information That Raises the Stakes on the Investigation of Border Patrol Critical Incident Teams (BPCITs) and Implicates Other Parts of CBP,” August 11, 2022, https://assets.nationbuilder.com/alliancesandiego/pages/409/attachments/original/1660253686/Letter_to_Congress_re_BPCIT_Aug_2022_r1.pdf?1660253686.

[39] “Abuse, Accountability, and Organizational Culture at U.S. Border Law Enforcement Agencies.”

[40] “CBP-Directive-4320-030B: Incident-Driven Video Recording Systems” (U.S. Customs and Border Protection, February 2022), https://www.cbp.gov/sites/default/files/assets/documents/2022-Feb/CBP-Directive-4320-030B-IDVRS-signed-508.pdf.

[41] “CBP Acting Commissioner Miller’s Statement Concerning Release of Body-Worn Camera Footage,” U.S. Customs and Border Protection, April 12, 2023, https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/national-media-release/cbp-acting-commissioner-miller-s-statement-concerning-release-body; “CBP Releases Body-Worn Camera Footage from Agent-Involved Shooting,” U.S. Customs and Border Protection, May 2, 2023, https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/national-media-release/cbp-releases-body-worn-camera-footage-agent-involved-shooting.

[42] “DHS Announces First Department-Wide Policy on Body-Worn Cameras,” U.S. Department of Homeland Security, May 23, 2023, https://www.dhs.gov/news/2023/05/23/dhs-announces-first-department-wide-policy-body-worn-cameras; “CBP Agents and Officers Begin Use of Body-Worn Cameras,” U.S. Customs and Border Protection, August 4, 2021, https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/national-media-release/cbp-agents-and-officers-begin-use-body-worn-cameras.

[43] “U.S. Customs and Border Protection Budget Overview Fiscal Year 2024 Congressional Justification” (U.S. Department of Homeland Security, March 9, 2023), https://www.dhs.gov/publication/congressional-budget-justification-fiscal-year-fy-2024.

[44] “DHS Office of Inspector General: Actions Needed to Address Long-Standing Management Weaknesses” (Washington: U.S. Government Accountability Office, June 3, 2021), https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-21-316.

[45] “Audits, Inspections, and Evaluations: CBP FIscal Year 2022,” DHS Office of Inspector General, accessed April 5, 2023, https://www.oig.dhs.gov/reports/audits-inspections-and-evaluations?field_dhs_agency_target_id=1&field_fy_value=2.

[46] “Abuse, Accountability, and Organizational Culture at U.S. Border Law Enforcement Agencies.”

[47] Lisa Rein, Carol D. Leonnig, and Maria Sacchetti, “Homeland Security Watchdog Previously Accused of Misleading Investigators, Report Says,” Washington Post, August 12, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2022/08/03/homeland-security-joseph-cuffari-watchdog-report/.

[48] Claudia Grisales, “DHS Watchdog Appointed by Trump Has Fueled an Exodus of Agency Lawyers, Sources Say,” NPR, October 12, 2022, https://www.npr.org/2022/10/12/1127014951/dhs-inspector-general-cuffari-trump-jan-6.

[49] Zagorin and Schwellenbach, “Protecting the Predators at DHS.”

[50] Nick Schwellenbach, “DHS Watchdog Staff Call on Biden to Fire Inspector General Cuffari” (Washington: Project on Government Oversight, September 23, 2022), https://www.pogo.org/investigation/2022/09/dhs-watchdog-staff-call-on-biden-to-fire-inspector-general-cuffari.

[51] Noah Lanard, “The DHS Inspector General Claimed to Have a Philosophy PhD. He Doesn’t.,” Mother Jones, accessed April 5, 2023, https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2020/05/the-dhs-inspector-general-claimed-to-have-a-philosophy-phd-he-doesnt/.

[52] Danielle Brian, “POGO Calls on Biden to Remove Inspectors General Cuffari, Ennis,” Project On Government Oversight, March 8, 2023, https://www.pogo.org/letter/2023/03/pogo-calls-on-biden-to-remove-inspectors-general-cuffari-ennis; Danielle Brian, “Opinion | A Promise Joe Biden Should Break,” Washington Post, August 2, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2022/08/02/fire-dhs-inspector-general-cuffari/.

[53] “DHS Delegates Criminal Misconduct Investigative Authority to CBP,” U.S. Customs and Border Protection, September 18, 2014, https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/national-media-release/dhs-delegates-criminal-misconduct-investigative-authority-cbp.

[54] Turberville and Rickerd, “An Oversight Agenda for Customs and Border Protection.”

[55] “Border Patrol Agents in Secret Facebook Group Faced Few Consequences for Misconduct” (Washington: U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Oversight and Accountability Democrats, September 14, 2021), https://oversightdemocrats.house.gov/cbp-report.

[56] Senior DHS Official, Interview with senior DHS official.

[57] “Secretary Mayorkas Directs DHS To Reform Employee Misconduct Discipline Processes,” U.S. Department of Homeland Security, June 16, 2022, https://www.dhs.gov/news/2022/06/16/secretary-mayorkas-directs-dhs-reform-employee-misconduct-discipline-processes.

[58] “Final Report of the CBP Integrity Advisory Panel.”

[59] “Abuse, Accountability, and Organizational Culture at U.S. Border Law Enforcement Agencies.”

[60] Turberville and Rickerd, “An Oversight Agenda for Customs and Border Protection.”

[61] “2023 Update to the Department Policy on Use of Force” (U.S. Department of Homeland Security, February 6, 2023), https://www.dhs.gov/publication/2023-update-department-policy-use-force.

[62] “Protect Dignity End Impunity” (Southern Border Communities Coalition, March 2023), https://assets.nationbuilder.com/alliancesandiego/pages/409/attachments/original/1679604157/SBCC_DIGNITY___IMPUNITY.v3.pdf?1679604157.

[63] “Code of Conduct for Law Enforcement Officials” (UN Office on Drugs and Crime, December 17, 1979), https://www.unodc.org/pdf/criminal_justice/Code_of_Conduct_for_Law_Enforcement_Officials_GA_43_169.pdf.

[64] “Final Report of the CBP Integrity Advisory Panel.”

[65] “Border Patrol Agents in Secret Facebook Group Faced Few Consequences for Misconduct.”

[66] Turberville and Rickerd, “An Oversight Agenda for Customs and Border Protection.”

[67] “U.S. Department of Homeland Security Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties Fiscal Year 2021 Annual Report to Congress.”

[68] “Interim Report of the CBP Integrity Advisory Panel.”

[69] “Congressional Record: Proceedings and Debates of the 117th Congress, Second Session.”

[70] Senior DHS Official, Interview with senior DHS official.

[71] “DHS Office of Inspector General.”

[72] Among many examples:

[73] Turberville and Rickerd, “An Oversight Agenda for Customs and Border Protection.”

[74] “National Border Patrol Council: Home,” National Border Patrol Council, accessed April 17, 2023, https://bpunion.org/.

[75] “Border Security Status Report Second Quarter, Fiscal Year 2022” (Washington: U.S. Department of Homeland Security, January 19, 2023), https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/2023-03/Departmental%20Management%20and%20Operations%20%28DMO%29%20%E2%80%93%20PLCY%20%E2%80%93%20Border%20Security%20Status%20Report%2C%20Second%20Quarter%2C%20FY%202022_0.pdf.

[76] Border Patrol Union – NBPC [@BPUnion], “Repeat after Us: Poor Economic Conditions Do Not Qualify Anyone for Asylum. The Vast Majority of Asylum Apps Are Fraudulent. Most Will Never Show for Their Court Date. It’s a Scam. Have a Nice Day.,” Tweet, Twitter, November 29, 2022, https://twitter.com/BPUnion/status/1597613491551993856; Will Carless, “‘Replacement Theory’ Fuels Extremists and Shooters. Now a Top Border Patrol Agent Is Spreading It.,” USA TODAY, May 15, 2022, https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2022/05/06/great-replacement-theory-border-patrol-racist-talking-point/9560233002/.

[77] “5 USC 7112: Determination of Appropriate Units for Labor Organization Representation” (U.S. Code), accessed April 17, 2023, http://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?req=(title:5%20section:7112%20edition:prelim)%20OR%20(granuleid:USC-prelim-title5-section7112)&f=treesort&edition=prelim&num=0&jumpTo=true.

[78] Zagorin and Schwellenbach, “Protecting the Predators at DHS.”

[79] Budd, Against the Wall: My Journey From Border Patrol Agent to Immigrant Rights Activist.

[80] Sullivan, “Top Border Patrol Official Resigned Amid Allegations of Improper Conduct.”

[81] John Burnett, “Border Patrol Completes Recruitment Drive Aimed At Women,” NPR, December 17, 2014, sec. National, https://www.npr.org/2014/12/17/371364713/border-patrol-completes-recruitment-drive-aimed-at-women; Turberville and Rickerd, “An Oversight Agenda for Customs and Border Protection.”

[82] “CBP Events Calendar,” U.S. Customs and Border Protection, April 14, 2023, https://www.cbp.gov/cbp-events-calendar.

[83] “CBP Policy on Nondiscrimination in Law Enforcement Activities and All Other Administered Programs,” U.S. Customs and Border Protection, accessed April 17, 2023, https://www.cbp.gov/about/eeo-diversity/policies/nondiscrimination-law-enforcement-activities-and-all-other-administered.

[84] Murdza and Ewing, “The Legacy of Racism within the U.S. Border Patrol.”

[85] Turberville and Rickerd, “An Oversight Agenda for Customs and Border Protection.”

[86] “CBP Highlights Top 2022 Accomplishments,” U.S. Customs and Border Protection, January 30, 2023, https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/national-media-release/cbp-highlights-top-2022-accomplishments; “Statement by Secretary Mayorkas on the President’s Fiscal Year 2024 Budget,” U.S. Department of Homeland Security, March 9, 2023, https://www.dhs.gov/news/2023/03/09/statement-secretary-mayorkas-presidents-fiscal-year-2024-budget.

[87] Natasha Pizzey and James Fredrick, “Forgotten on ‘La Frontera’: Mexican Children Fleeing Violence Are Rarely Heard,” WOLA, January 22, 2015, https://www.wola.org/analysis/forgotten-on-la-frontera-mexican-children-fleeing-violence-are-rarely-heard/.

This report was made possible, and tremendously improved, by editing, design, research, communications, and content contributions from Kathy Gille, Joanna Williams, Ana Lucía Verduzco, Zaida Márquez, Sergio Ortiz Borbolla, Milli Legrain, and Felipe Puerta Cuartas. We could not do this work without the generosity of our supporters; please become one of them.