HONDURAS / Areas of progress

4.1

National Law in Accordance with International Standards

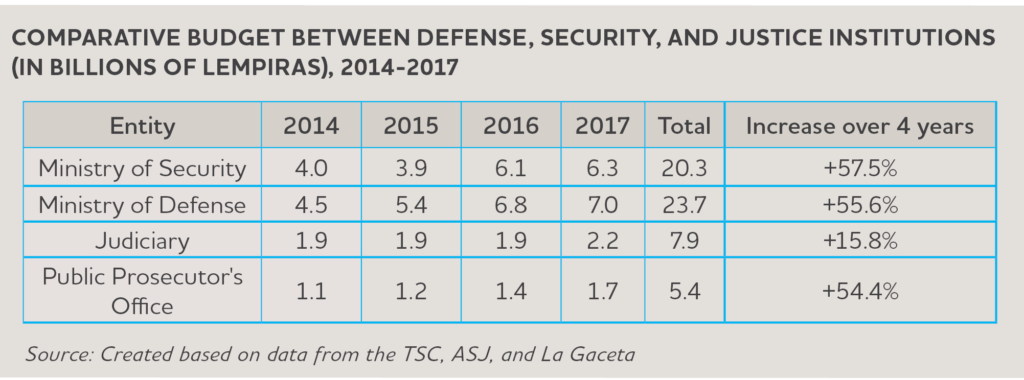

In recent decades, Honduras has made legal advances to help prevent, detect, and punish violence and organized crime. Some important mechanisms were approved to combat organized crime, such as wiretapping, controlled deliveries, and use of undercover agents. However, the refusal to approve the Law on Effective Collaboration or interest in strengthening the witness protection program contradicts these advances. In general, regulations passed since 2010 are reactive and militaristic in nature, concentrating power in the executive branch at the expense of legislative and judicial branches. In addition to these measures reflecting the prioritization of security and defense, rather than the justice sector, they have been accompanied by legislation that restricts access to public information.

For example, despite the existence of a Law to Control Firearms, Explosives, and Similar Items, its restrictions are relaxed when it comes to carrying weapons and granting licenses. This regulation is in place despite the fact that 77 percent of homicides are committed with a firearm.

HONDURAS / Areas of progress

4.2

Investigative Capacities and Prosecution of Criminal Networks and Organized Crime

The Public Prosecutor’s Office has various entities for investigating possible offenses involving violence and organized crime. It has two directorates, a technical agency for investigation, four special prosecutors’ offices, and six specialized units to investigate homicides, femicides, kidnapping, extortion, human trafficking, illicit trafficking, asset laundering, and criminal conspiracy, among other crimes. However, the Public Prosecutor’s Office allocated $40.9 million, or 18.9 percent of its total budget, to these entities. As demonstrated in the table, the majority of funds were allocated to the Technical Agency of Criminal Investigation (ATIC for its title in Spanish), followed by the National Directorate for the Fight against Drug Trafficking. The Special Prosecutor’s Office for Women (FEM) received 8.3% of the funds and the witness protection program only received 2%. The budget of the FEM contrasts with its demand on human resources, having received 69,000 complaints in the period under study.

By the end of 2017, these directorates, prosecutors’ offices and units accounted for 536 total staff, or 14 percent of total staff of the Public Prosecutor’s Office. The ATIC had the largest number of personnel, followed by the Prosecutor’s Office for Crimes against Life and the Prosecutor’s Office dedicated to investigating organized crime.

By the end of 2017, these directorates, prosecutors’ offices and units accounted for 536 total staff, or 14 percent of total staff of the Public Prosecutor’s Office. The ATIC had the largest number of personnel, followed by the Prosecutor’s Office for Crimes against Life and the Prosecutor’s Office dedicated to investigating organized crime.

The judicial branch has created specialized bodies for fighting violence and organized crime, including Jurisdictional Bodies with National Territorial Competence, a Criminal Court of First Instance and a Criminal Appeals Court with National Jurisdiction on Extortion Matters and two Special Anti-Domestic Violence Courts.

The judicial branch has created specialized bodies for fighting violence and organized crime, including Jurisdictional Bodies with National Territorial Competence, a Criminal Court of First Instance and a Criminal Appeals Court with National Jurisdiction on Extortion Matters and two Special Anti-Domestic Violence Courts.

HONDURAS / Areas of progress

4.3

Effectiveness of Investigations of Criminal Networks and Organized Crime

Based on the information provided by the Public Prosecutor’s Office regarding crimes against life between 2014 and 2017, the Prosecutor’s Office received 20,053 complaints of homicide, 1,042 of murder, 51 of parricide, and 123 of femicide. In that four-year period, the Public Prosecutor’s Office filed charges in 303 cases for the offense of homicide, 711 for murder, 44 for parricide, and 47 for femicide.

For crimes related to organized criminal activity, the Public Prosecutor’s Office received 6,488 formal complaints between 2014 and 2017. Of these, 42.7% (2,775) were for drug trafficking (including small-scale street dealing), 31.2% (2,024) for extortion, 7.8% (505) for illicit trafficking, 4.6% (229) for human trafficking, 4.5% for illegal manufacture and trafficking of weapons, 3.5% (229) for asset laundering, and less than 3% for kidnapping and unlawful association. In that period, the Public Prosecutor’s Office filed 1,244 criminal charges for extortion, 85 for kidnapping, 30 for human trafficking (between 2016 and 2017), 37 for money laundering (between 2014, 2015, and 2016), and 52 for the illegal manufacture and trafficking of weapons. No data was available on charges filed for crimes of drug trafficking or illicit trafficking.

For crimes related to organized criminal activity, the Public Prosecutor’s Office received 6,488 formal complaints between 2014 and 2017. Of these, 42.7% (2,775) were for drug trafficking (including small-scale street dealing), 31.2% (2,024) for extortion, 7.8% (505) for illicit trafficking, 4.6% (229) for human trafficking, 4.5% for illegal manufacture and trafficking of weapons, 3.5% (229) for asset laundering, and less than 3% for kidnapping and unlawful association. In that period, the Public Prosecutor’s Office filed 1,244 criminal charges for extortion, 85 for kidnapping, 30 for human trafficking (between 2016 and 2017), 37 for money laundering (between 2014, 2015, and 2016), and 52 for the illegal manufacture and trafficking of weapons. No data was available on charges filed for crimes of drug trafficking or illicit trafficking.

Between 2014 and 2017, the Public Prosecutor’s Office received 76,992 formal complaints for alleged crimes committed against women. Of all the complaints, 38.1% regarded domestic violence, 16.9% physical violence, 16.2% intrafamily violence and 6.2% sexual assault. It’s important to note that the Public’s Prosecutor’s Office did not provide data on criminal charges it filed for these offenses.

Between 2014 and 2017, the Public Prosecutor’s Office received 76,992 formal complaints for alleged crimes committed against women. Of all the complaints, 38.1% regarded domestic violence, 16.9% physical violence, 16.2% intrafamily violence and 6.2% sexual assault. It’s important to note that the Public’s Prosecutor’s Office did not provide data on criminal charges it filed for these offenses.