(AP Photo/Eric Gay)

(AP Photo/Eric Gay)

Preliminary information indicates that U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) encountered 210,000 undocumented migrants in July 2021. That is the largest number of encounters in a month since 2000. Due to a high number of repeat crossings, the actual number of people encountered was smaller.

Though numbers of individual migrants are not yet record breaking, they could be soon. We are entering a historic moment of large-scale migration. The coming months will demand of the United States a determined, rights-respecting, and innovative response—not another crackdown.

Throughout Latin America—throughout the world—the COVID-19 pandemic has devastated economies to a degree not seen since the 1930s. In many states, it has also devastated governance, worsening public security, leaving people unprotected and, in some cases, preyed upon by authoritarian regimes. Travel restrictions are starting to lift, and the United States is one of many countries around the world again becoming major migration destinations.

Anecdotal evidence points to growing numbers of people traveling along migration routes through Mexico (which by the end of August will break its own annual record for asylum seekers) and as far back as the jumping-off point between Colombia and Panama. In May and June, about a quarter of encountered migrants at the U.S.-Mexico border—and nearly half of migrants arriving as families—were from countries other than Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, or Honduras. That has never happened before.

In the short term, there is little the Biden administration can do to reduce this increase in migration. At the moment, though, U.S. policy seems to be moving in two very different directions.

Support human rights on both sides of the border by joining the Beyond the Wall campaign:

Support the Beyond the Wall campaign

On one hand, in late July the White House released a series of strategies that lay out, in general terms, the administration’s priorities for border security, immigration enforcement, access to asylum, regional cooperation, and addressing the root causes of migration from the region. Based primarily on executive orders issued during the first weeks of Joe Biden’s presidency, the strategies include the collaborative migration management strategy, a strategy on addressing the root causes of migration in Central America, and a blueprint for reforming the U.S. immigration system.

Complementing the rollout of these strategies, during the past seven months the administration has enacted several measures to undo the damage done by President Donald Trump’s cruel and inhumane immigration policies, including ending the “Remain in Mexico” program and asylum cooperation (“safe third country”) agreements, reinstating and expanding the Central American Minors program, creating a task force to reunify separated families, and restoring aid to Central America.

On the other hand, announcements made in recent days suggest a shift at the border toward sending more migrant families back to their countries of origin, without ensuring that they are given the opportunity to request asylum or another form of protection in the country. And while the Biden administration’s “blueprint” document affirms that “asylum and other legal migration pathways should remain available to those seeking protection,” the administration is also maintaining “Title 42,” the Trump-era pandemic border policy that expels as many adults and families as possible from the United States, as quickly as possible, and often into Mexico.

Subscribe to weekly updates about what’s happening at the U.S.-Mexico border:

Subscribe to the weekly border update

Enacted by the Trump administration due to alleged public health concerns (and rejected by public health experts as having “no scientific basis as a public health measure”) Title 42 blocks most migrants from requesting asylum or other forms of protection. Press reporting in early July had indicated that the administration was likely to stop applying Title 42 to asylum-seeking families after the end of the month. In the end, though, the administration—citing the COVID-19 delta variant and fearing rising migrant numbers—abandoned that plan. Currently, single adults and families continue to be expelled in large numbers.

The Biden administration’s “blueprint” also references a Department of Homeland Security (DHS) announcement that it is resuming expedited removal at the border of certain families who cannot be expelled under Title 42, prompting concerns that asylum seekers may be unlawfully deported if CBP agents deny them the ability to seek protection.

Maintaining Title 42 will continue to harm asylum seekers and expose them to danger in Mexican border towns. Expedited removal and fast-tracking asylum cases through the courts for families arriving at the border also risks returning people with protection needs back to the threats they were fleeing.

In the long term, the Biden administration has developed strategies that are a welcome step towards reversing the harm done by the Trump administration, increasing access to protection in the region, and addressing the drivers of migration. In the short term, though, the administration’s current policies are set on deterrence and sending a “do not come” message to would-be migrants and asylum seekers.

As migration increases regionwide during this difficult historic moment, we are concerned that this short-term, deterrence-based approach could intensify. That would be a grave error, and would waste an opportunity to forge a new path for countries worldwide facing humanitarian emergencies. That path is foreseen in our own immigration laws, which enshrine the right for people under threat to petition for protection in the United States.

The current moment, and the coming months or years, pose daunting challenges to countries likely to receive large numbers of fleeing people. It could also be a turning point toward a more humane, accommodating approach to migration. That will depend on the Biden administration’s willingness to show leadership on migration policy.

That in turn will mean building up a well-functioning system to receive and process elevated numbers of migrants and asylum seekers, then fairly and promptly adjudicate their claims without detaining them. Past U.S. administrations, from both parties, have resisted doing this, but the reality of migration demands it.

Understanding this moment requires examining the current dynamics at the border, the likelihood of further migration increases, the futility of short-term deterrence, and how the Biden administration’s policies will impact migrants and asylum seekers and the decisions they make.

What we are seeing at the U.S.-Mexico border is a reversion to patterns seen in 2014, 2016, and especially in 2018-19. Mainly because the Trump administration spent four years seeking simply to block all migration, the U.S. government failed to adjust its border and migration apparatus to match these patterns.

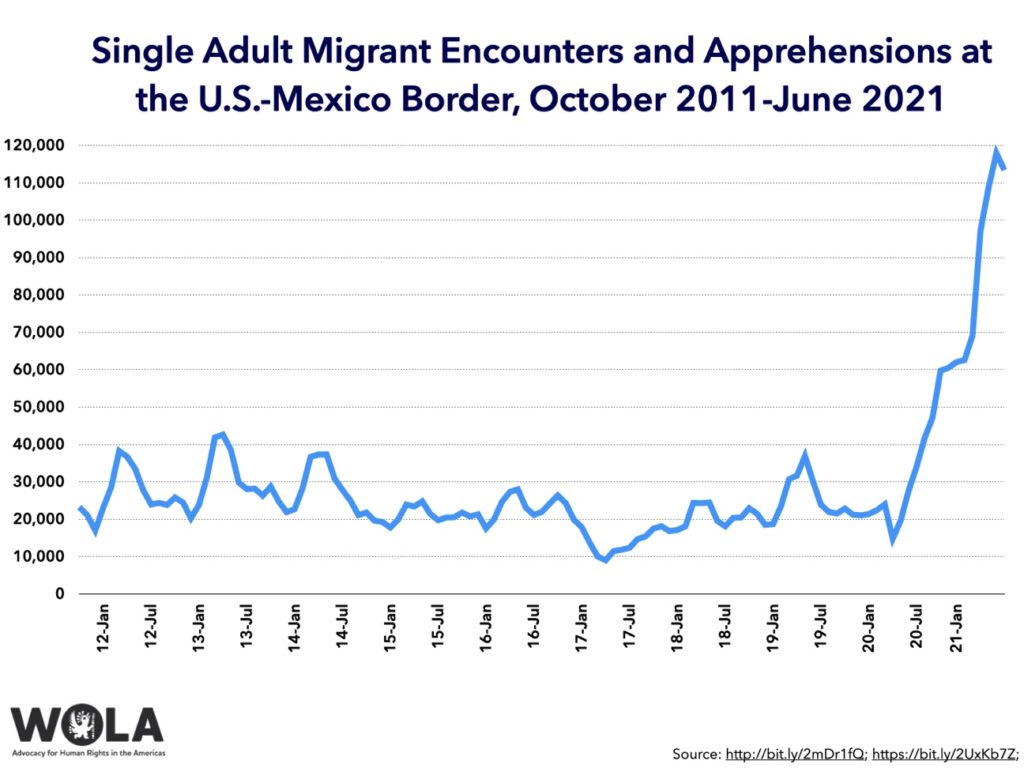

One element is new right now: a sharp jump in encounters with single adults at the border. The pandemic’s devastation of economies, and the ease of repeat crossings after rapid Title 42 expulsions, has increased the flow of migrants who wish to avoid apprehension.

While there is a lot of double and triple-counting, encounters with single adults—some of whom are asylum seekers who wish to file a claim with U.S. officials, but many of whom seek to avoid border agents—are currently about five times greater than they were before the pandemic. If Title 42 ends, and apprehended adults end up spending more time in U.S. custody, we can expect fewer repeat crossings and a reduction in single adults.

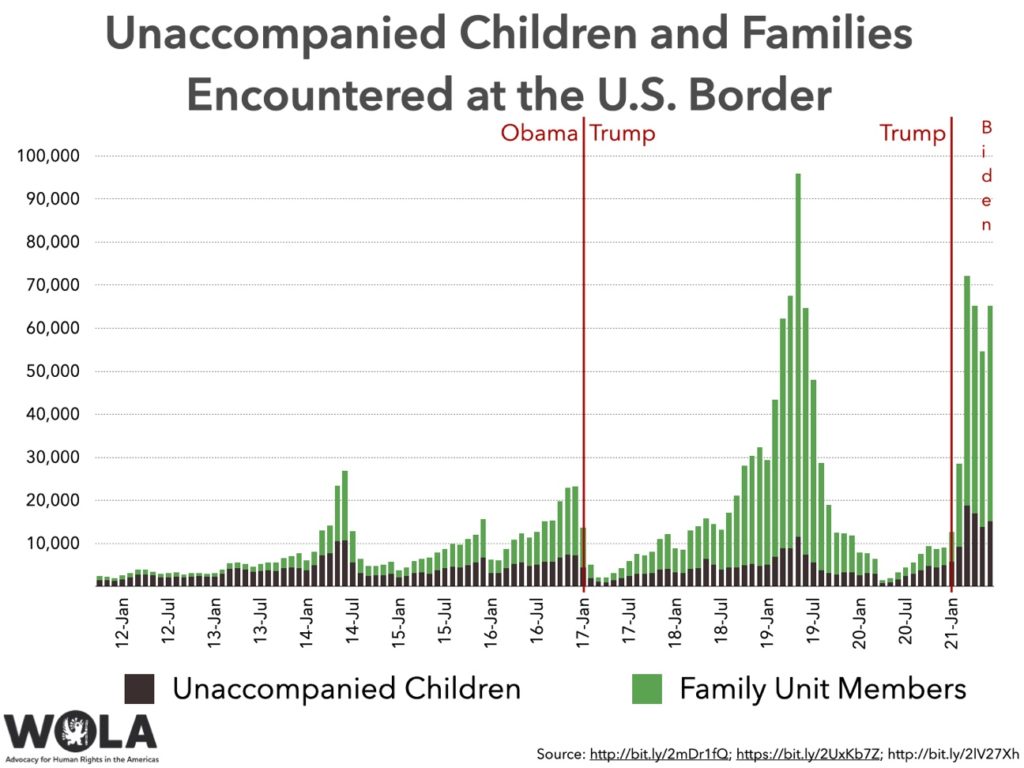

Alongside the increase in single adults, since March, arrivals of families and children have increased sharply. Preliminary July 2021 data point to 80,000 family members and 19,000 unaccompanied children taken into custody—both at or near record levels. Large flows of children and families are something the United States saw consistently between the first “child migrant crisis” in spring 2014 and the onset of COVID-19 in 2020.

Those flows were reduced, temporarily, by crackdowns: Mexico’s U.S.-encouraged “Southern Border Plan” in 2014-15, a 2017 decline in migration in the initial months after Donald Trump’s inauguration, the Trump administration’s cruel “Remain in Mexico” policy, and then COVID-19 border closures in 2020. Migration consistently recovers after these short-term crackdowns, which violate the right to seek asylum, ignore the reasons that people are migrating, and fail to reckon with the reality that our entire region is in a period of historically high migration.

Even after seven years of large numbers of protection-seeking migrants, the U.S. government has failed to adjust its border and migration agencies’ doctrine, personnel, or infrastructure, which were designed to address economic migration, primarily of single adults.

The United States still lacks the ability to efficiently process and adjudicate large numbers of non-detained asylum seekers, especially families and unaccompanied children.

The result is that every time migrant numbers recover, the U.S. border and migration apparatus gets caught flat-footed by a “crisis.” We’re seeing it again now.

In March 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) under the Trump administration first put Title 42 provisions in place.

Since then, WOLA—along with hundreds of other organizations, Members of Congress, public health experts, and the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)—has called for an end to the expulsions policy, and for the adoption of measures to safeguard public health while keeping the U.S. border open to asylum seekers, in line with legal guidance issued by the UN Refugee Agency and recommendations of public health experts.

Title 42 has faced multiple legal challenges, as rapidly expelling migrants at the border without the opportunity to seek protection violates the principle of non-refoulement (the international laws and norms that forbid countries from returning asylum seekers back to situations of danger). In November 2020, the ACLU won a preliminary injunction that challenged the expulsion of unaccompanied children at the border under Title 42; although a federal appeals court issued a stay on the injunction in January, the Biden administration has allowed unaccompanied children from non-contiguous countries to seek protection in the country. In January, the ACLU filed another class action suit on behalf of families challenging Title 42 expulsions. While the Biden administration was in talks with the ACLU about ending the lawsuit, because the administration refused to stop expelling families by July 31, the ACLU and other organizations on the lawsuit announced on August 2 that they were headed back to court and are seeking a preliminary injunction to stop its implementation. Administration officials insist that they are not using Title 42 as a deterrent: they portray it as a CDC measure to prevent the spread of COVID-19. The facts indicate otherwise.

Administration officials insist that they are not using Title 42 as a deterrent: they portray it as a CDC measure to prevent the spread of COVID-19. The facts indicate otherwise.

Media reports have revealed that the decision to adopt Title 42 was inappropriately political: then-Vice President Mike Pence overruled CDC scientists who “said there was no evidence the action would slow the coronavirus.” The list of experts who insist that expulsions are not necessary or effective in stemming COVID-19 includes the UNHCR, Physicians for Human Rights (PHR), the Harvard Public Health Review, and a long list of public health professors. In fact, a late July PHR report contends that Title 42’s implementation may make the situation worse: “Every aspect of the expulsion process, such as holding people in crowded conditions for days without testing and then transporting them in crowded vehicles, increases the risk of spreading and being exposed to COVID-19.”

The public health arguments underlying Title 42 expulsions make little sense. U.S. citizens and “essential” travelers who arrive by land are admitted at the border without providing any proof of a negative COVID-19 test; there is no reason to believe that they are any less likely to be infected. The same goes for travelers who arrive by air, who are not subject to border closures. During the last week of July in Texas, 11.6 percent of COVID-19 tests were positive. Among migrants arriving at the border in Texas’s busy Rio Grande Valley region, the positivity rate was much lower—about 7 percent. In addition, networks of humanitarian groups were placing COVID-positive migrants in quarantine, while more than 85 percent of all arriving migrants were getting vaccinated by these groups. The administration also announced on August 3 that it would begin vaccinating migrants who are waiting at the border to be processed by CBP.

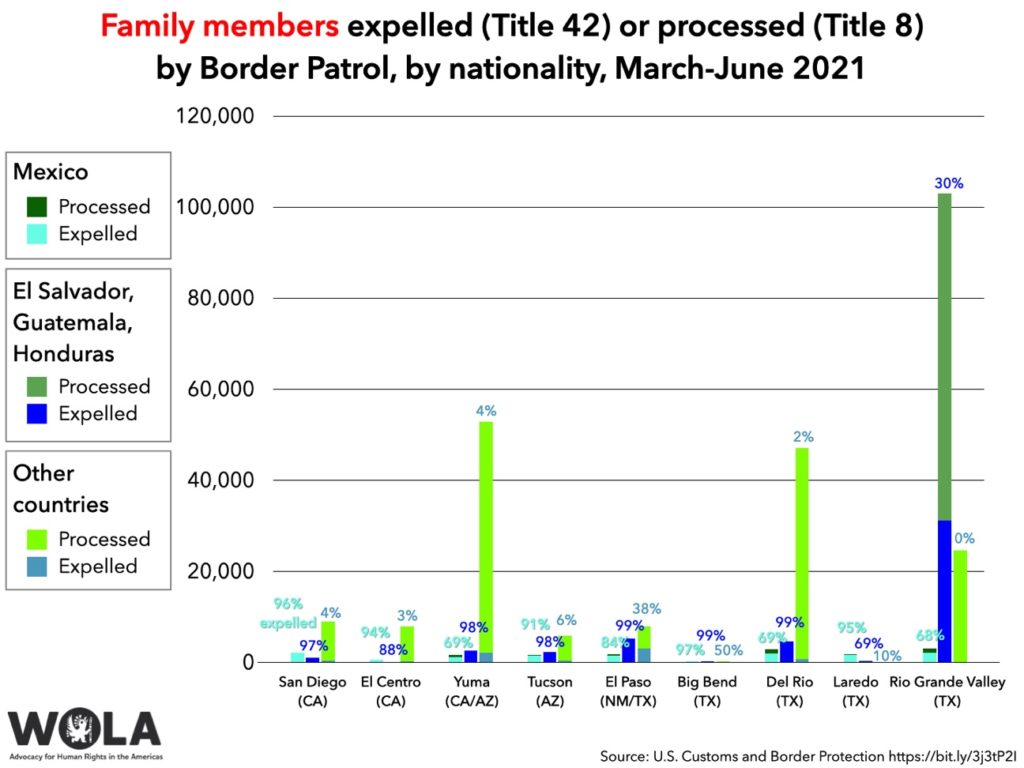

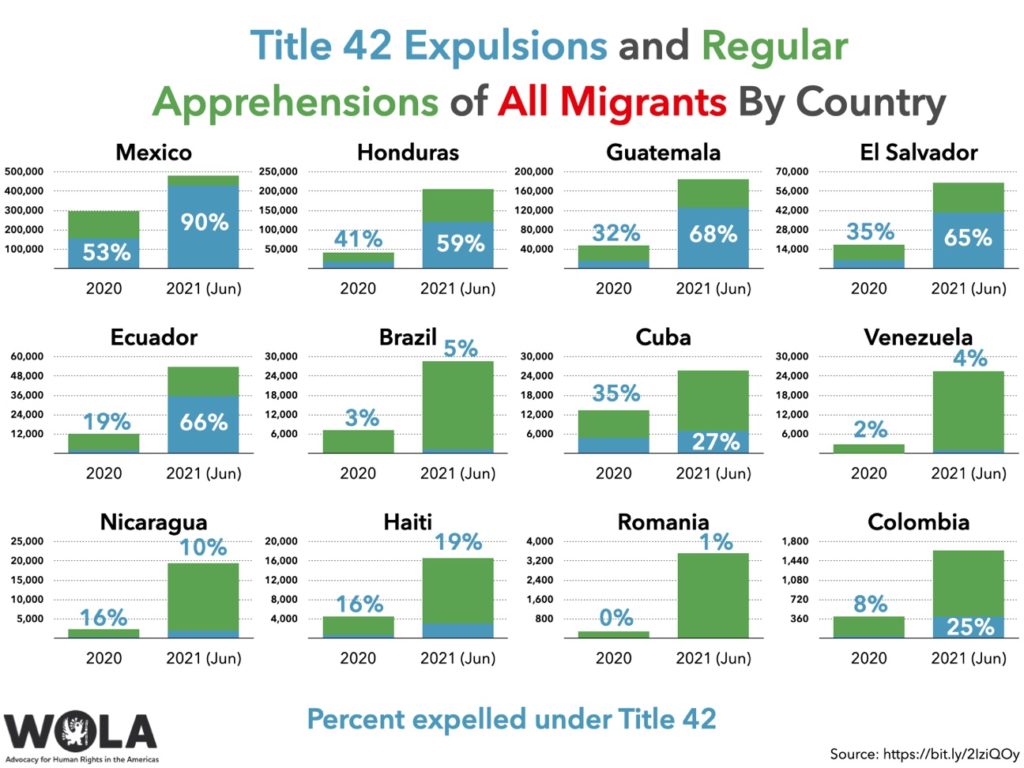

The purported public health justification for Title 42 is also undermined by its inconsistent application across the border, and across nationalities. While all unaccompanied children from non-contiguous countries are processed into the United States, right now there appears to be little rhyme or reason regarding who else is able to enter. Much seems arbitrary or based on where migrants crossed the border.

Families from Mexico get expelled nearly everywhere, though for some reason it happens less often in Border Patrol’s Rio Grande Valley, Del Rio, and Yuma sectors. Families from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras are heavily expelled everywhere except across from Tamaulipas, Mexico, where some families (presumably those with small children) usually avoid expulsion. Families from other countries rarely get expelled, though a lot of Ecuadorian families have been expelled from El Paso.

Single adults, meanwhile, can expect to be expelled everywhere along the border—if they are from Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, or Honduras. If they come from other countries, they stand very little chance of being expelled, except in El Paso and Big Bend where Title 42 has been applied to large numbers of Ecuadorian single adults. These individuals probably had some migratory status in Mexico—but so do many Venezuelan adults, and they are rarely expelled.

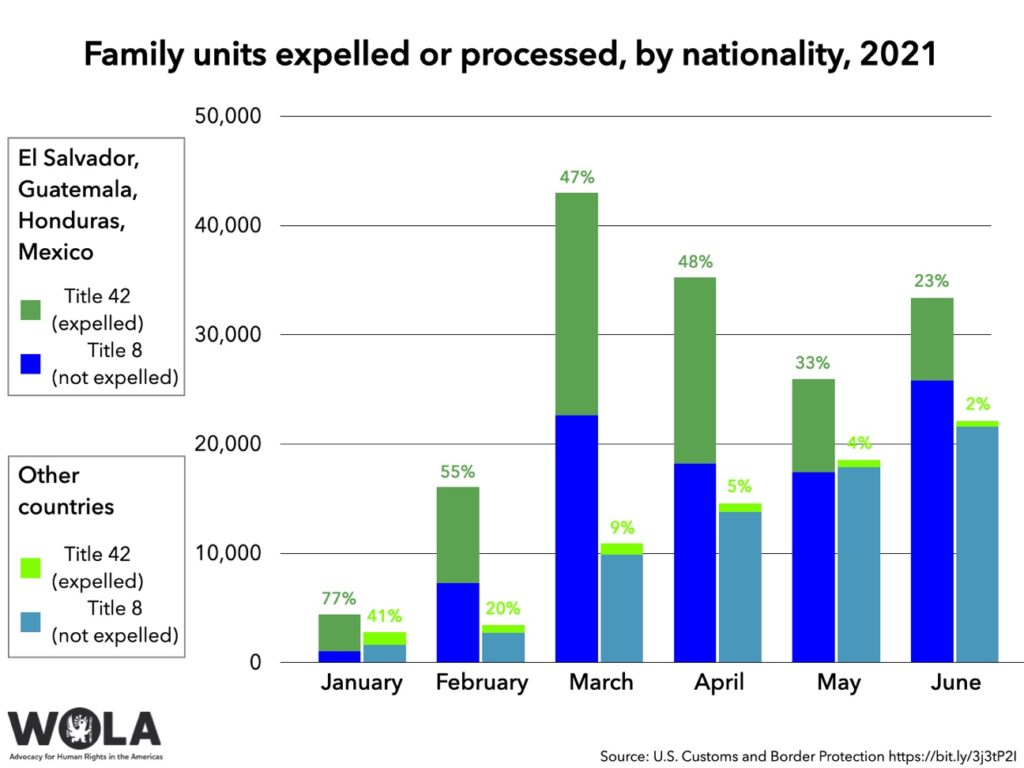

Take all this together, and we see a wild variation of expulsion outcomes by nationality, as this chart indicates:

Perhaps because of those odds, and because of regional economic devastation and political unrest, the border is seeing large increases in migration from countries other than Mexico and Central America. While accounting for nearly half of all families, in May families from these “other” countries were just over half of the families who didn’t get expelled:

This distorted makeup of the migrant population may be a direct result of Title 42’s inconsistent application—an inconsistency that casts doubt on the expulsion policy’s claim to be a public health measure.

As part of the ACLU’s negotiations with the Biden administration, the most vulnerable migrants—those who are in danger in Mexico, have medical conditions, or face other hardships—could request an exemption from Title 42 provisions through a consortium of organizations working on the border who help identify them and request admission. While this process led to the admission of about 16,000 asylum seekers, protecting them from immediate harm, even the organizations involved recognized that the real problem is that Title 42 remains in place.

On July 30, two of the organizations that were part of the consortium announced that they would no longer participate in the process, given the Biden administration’s failure to give justification for why it was continuing with a program they considered violates international law. Given the restart of ACLU-led litigation challenging Title 42, the administration announced it was ending the exemptions to Title 42 on August 9, but that it would still honor pending appointments to enter the country

With Title 42 in place, it is nearly impossible for an asylum seeker to petition for protection at a land port of entry. Even most asylum seekers apprehended between the ports of entry by Border Patrol get expelled.

This creates an incentive to try to avoid apprehension, traveling through dangerous deserts and wilderness areas. As noted above, the population of migrants seeking to avoid apprehension—many of them single adults—has jumped during the pandemic.

All of this means that far more people are trying to migrate through severely inhospitable border regions, at the hottest time of the year. The border region is no doubt experiencing a jump in the number of people dying on U.S. soil right now.

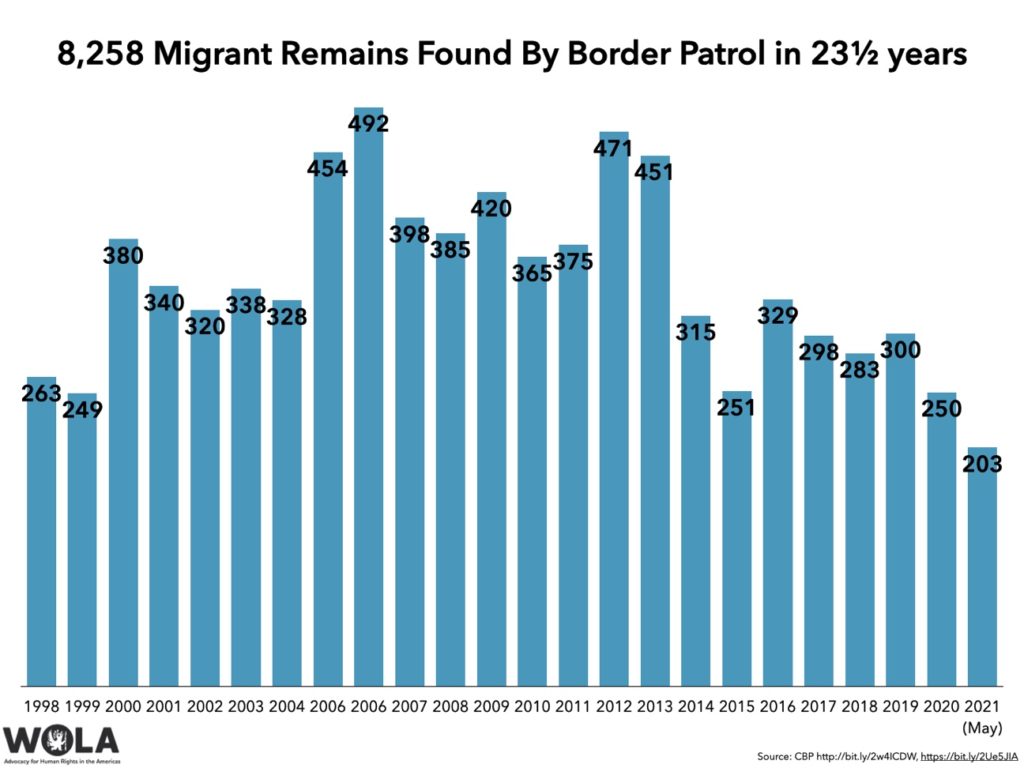

A San Antonio television station obtained from Border Patrol the agency’s most recent count of migrant remains encountered on U.S. soil, through May 2021. Since 1998, Border Patrol has found the bodies of 8,258 individuals who perished from dehydration, exposure, drownings, animal attacks, and other causes while traveling through wilderness areas. It is an enormous death toll for a phenomenon that receives such scarce attention.

In the first eight months of fiscal year 2021 (October 2020 through May 2021), Border Patrol reported finding 203 remains. This is quite high given that the hottest and deadliest months of the year—June through September—remained to be counted, and that the U.S. southwest has been recording higher-than-normal temperatures. By the time the 2021 fiscal year ends, on September 30, this could end up being the deadliest year in Border Patrol’s data since at least 2013.

Since 1998, the sectors where Border Patrol has found the most remains have shifted geographically, from California to Arizona to southeast Texas, and now, increasingly, to south-central Texas. So far this year, Border Patrol has found the most bodies in its Del Rio sector, a vast unpopulated region between Big Bend National Park and Laredo.

Border Patrol is the only entity keeping a national count of migrant deaths, but it “only counts those it handles in the course of its work,” the Guardian explains. Local organizations tend to find much larger numbers of dead in their home regions.

The Arizona-based group Humane Borders, mapping data from the Pima County medical examiner’s office, reported 127 sets of remains during the first half of the 2021 calendar year, way up from 96 during the first half of 2020. By contrast, Border Patrol reports finding only 22 remains in its Arizona sectors (Tucson and Yuma) since October 2020.

In the very rural Big Bend sector of west Texas, Border Patrol has found 32 remains of migrants so far in fiscal 2021, way up from 15 in all of 2020 and far more than the sector’s prior high of 10 (2018).

In Brooks County, Texas, about 80 miles north of where Texas’s Rio Grande Valley region borders Mexico, large numbers of migrants die while trying to circumvent a longstanding Border Patrol highway checkpoint. There, the county sheriff reports finding 50 bodies in calendar year 2021, more than in any full year since 2017. The Sheriff’s Office found 16 just in June 2021, making this the worst June in Brooks County since 2012.

Border Patrol, too, is reporting a big increase in rescues of migrants in distress.

This is a tragic year for migrant deaths at the border, exacerbated by the Title 42 expulsions policy.

In addition to keeping Title 42 in place, the Biden administration recently announced another policy that is sparking outrage from human rights and humanitarian organizations: expedited removal for families that are excluded from Title 42 provisions.

Expedited removal allows CBP officers to place migrants in deportation proceedings within a couple of hours, without the right to appeal the decision before an immigration court. Essentially, it’s a fast-track screening process—a short interview where officers frequently fail to detect and identify asylum seekers who should be referred for a credible fear interview. . The fact that CBP agents exclusively handle these screenings has long raised concerns over due process and the increased risk of erroneous deportations.

The use of expedited removal for vulnerable families at the border means that some may be rapidly deported back to the very dangers they were fleeing without due process. Black and Indigenous asylum seekers are at a particular risk for deportation without due process given language barriers and racial bias. These concerns have led over 80 faith-based, immigration, and human rights groups to call on current DHS Secretary Mayorkas to reject using expedited removal.

It is not yet clear how broadly the Biden administration will be applying expedited removal at the border, and which populations will be its key target. DHS states that “certain family units who are not able to be expelled under Title 42 will be placed in expedited removal proceedings.” A New York Times article suggests that the “certain family units” will likely be those families who are crossing through the Rio Grande Valley where, given their numbers and nationalities, including from Brazil, Venezuela, and India, the Mexican government has determined not to accept expelled families. On July 30, DHS announced the first flights of families who were returned to Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras; however, many families scheduled to be on the flights were pulled after testing positive for COVID-19, with only 73 family members returned to their home countries.

The blueprint issued by the administration affirms that it is working to improve the expedited removal process “to fairly and efficiently determine which individuals have legitimate claims for asylum and other forms of protection.” But there are no details on how they are doing so.

It is not yet clear how much the use of expedited removals at the border will impact the number of migrants being expelled to Mexico through Title 42.

At a minimum, Mexican nationals will continue to be returned, blocking their possibility of accessing asylum (notably, the Mexican government reported receiving 109,553 repatriated Mexicans between January and June 2021). And as the Biden administration continues to maintain the ports of entry closed to asylum seekers, thousands of asylum seekers are waiting in Mexican border towns, often in dramatically miserable conditions, for a chance to enter the United States the “right way” to request protection.

By one estimate from May 2021, there are approximately 18,680 asylum seekers on waitlists in eight Mexican border cities. (Not everyone on a list may still be waiting at the border; there’s also a strong possibility that the lists are undercounting, with asylum seekers unable or unwilling to add their names to a list). Encampments in Mexican border towns like Tijuana and Reynosa also point to the high number of people waiting in Mexican border towns under the expectation that, sooner rather than later, the Biden administration will reopen the border to asylum seekers.

This population is extremely vulnerable and easy prey for criminal organizations that frequently rob, extort, and kidnap them. Between January and June 2021, Human Rights First and partner organizations registered 3,250 kidnappings and other attacks against migrants and asylum seekers who were expelled or stranded at the border.

As happened with the asylum seekers sent to Mexico under the “Remain in Mexico” program, and after more than a decade of documented cases of crimes against migrants and asylum seekers in Mexico, the Mexican government has failed to implement policies to protect this vulnerable population and effectively investigate and prosecute those responsible for these crimes. By maintaining the border closed to most asylum seekers, and expelling others, the Biden administration continues to advance the harmful deterrence policies of past U.S. administrations and ultimately shares responsibility for the risks this population faces.

In recent years, we have seen nations around the world handle migration events in starkly inhumane ways. The Clinton administration kept Haitian asylum seekers in a camp at Guantánamo Bay and refused to settle them in the United States. In the mid-2010s, many European countries closed borders and tightened asylum laws in response to migrants fleeing Syria, Afghanistan, and Iraq, many of whom were made to remain in Turkey and Libya. Today, countries like Chile, Ecuador, and Peru place severe limits on legal status for fleeing Venezuelans.

The Biden administration has a historic opportunity to show that there is a better, more humane way to handle the large-scale protection-seeking migration events that are becoming more common worldwide. This means breaking the cycle of migration crises and border crackdowns that the U.S. border apparatus has gone through during the past seven years. It means adjusting policy to reality by building the infrastructure necessary to receive, process, and adjudicate large numbers of migrants with humanitarian needs, while also focusing on strategies for regional access to protection and to address the drivers of migration.

It must build this better model, though, at a moment when the world is struggling to respond to and recover from the pandemic, and in the face of opposition from a vocal anti-immigrant minority at home. The Biden administration has taken some important steps during its first six months, but its bifurcated, inconsistent approach casts doubt on whether it is seizing this opportunity to adjust the U.S. response to protection-seeking migration, particularly at the border.

The first step on the road to a new, consistent, rights-respecting approach is to end the use of Title 42. As high current migration numbers indicate, the expulsion policy isn’t even serving its supporters’ goals: it’s neither deterring migrants nor containing COVID-19.

It’s likely that lifting Title 42 may cause a short-term increase in migration of children and families (though perhaps some reduction in single adult repeat border crossers). This may tax border infrastructure in a way that U.S. border authorities have, in fact, dealt with in the past—and for now, the answer is more capacity for processing, alternatives to detention, and adjudication.

As WOLA laid out in a mid-2020 analysis, the United States is capable of managing large numbers of migrants in a humane and rights-respecting manner. It starts with recognizing that an increased number of asylum-seeking migrants is not a border emergency, but an administrative challenge.

Support human rights on both sides of the border by joining the Beyond the Wall campaign:

Support the Beyond the Wall campaign

Our ports of entry can accommodate asylum seekers without waitlists, and with no need to rely on smugglers to cross in between the ports, where Border Patrol operates. This would mean modernizing and properly staffing our ports of entry and, where needed, opening up processing centers near ports. These processing centers need not be staffed by law enforcement-trained agents.

Once processed, those with protection claims need not be placed in detention while awaiting adjudication of those claims. They can be enrolled in alternatives-to-detention programs, in which case managers monitor asylum seekers while they live in the United States, ensure that they report for their court dates and facilitate access to counsel and other services. Such programs, when tried, have proved very effective at ensuring that asylum seekers attend their hearings, and they come at a fraction of the cost of detention.

In most cases, migrants’ petitions for asylum or protection should not require years of waiting for immigration courts to act while they remain, their futures uncertain, inside the United States. Reducing asylum seekers’ wait time in the U.S. interior requires increasing courts’ capacity: more judges and more courtrooms, reducing the number of cases per judge. Hiring and training of additional asylum officers and empowering them to decide many cases of those who petition for protection at the border—while maintaining due process and the ability to appeal to an immigration court—can do much to reduce courts’ caseloads. This, however, should not be done through an expedited removal process.

For its part, the Mexican government should take immediate steps to support the steadily growing population of asylum seekers, expelled migrants, and repatriated Mexicans in Mexican border towns, even as the United States and Mexico continue meeting to discuss deepening cooperation to address root causes of region-wide migration.

Apart from not obstructing the work of shelters and civil society organizations, at a minimum the Mexican government should provide security in areas where migrants are known to be at risk—such as around the ports of entry, encampments, and bus stations—and actively target for investigation and prosecution the criminal networks preying on migrants in these border towns. Any migrant freed from a kidnapping ring should be given the possibility to request a humanitarian visa in Mexico in order to pursue a criminal complaint against the aggressor. The recently announced Department of Justice-DHS Joint Task Force Alpha offers another possibility for coordination with Mexican authorities to investigate transnational criminal networks who prey on migrants, including cases of kidnapping and sexual assault.

At a time of historically high migration, the leaders of recipient and transit countries must scale up capacities to do what their laws say: to guarantee the right to seek asylum or humanitarian protection.

Desire to avoid a perceived “border crisis” will tempt some in the U.S. government to ignore or slow-walk compliance with the law, recurring to dubious, cruel, and ultimately ineffective measures like Title 42 expulsions or encouraging neighboring countries to militarize their responses to migration. We urge the Biden administration to resist that temptation.

A year and a half into this stubborn pandemic, the hemisphere and the world are entering a moment of peak migration. This moment offers the United States a key opportunity to demonstrate global leadership. Leadership means rejecting political expediency, upholding humanitarian principles enshrined in U.S. law, and forging a new model for calmly and efficiently administering large-scale migratory flows.