EL SALVADOR / Areas of progress

3.1

Levels of Public Trust

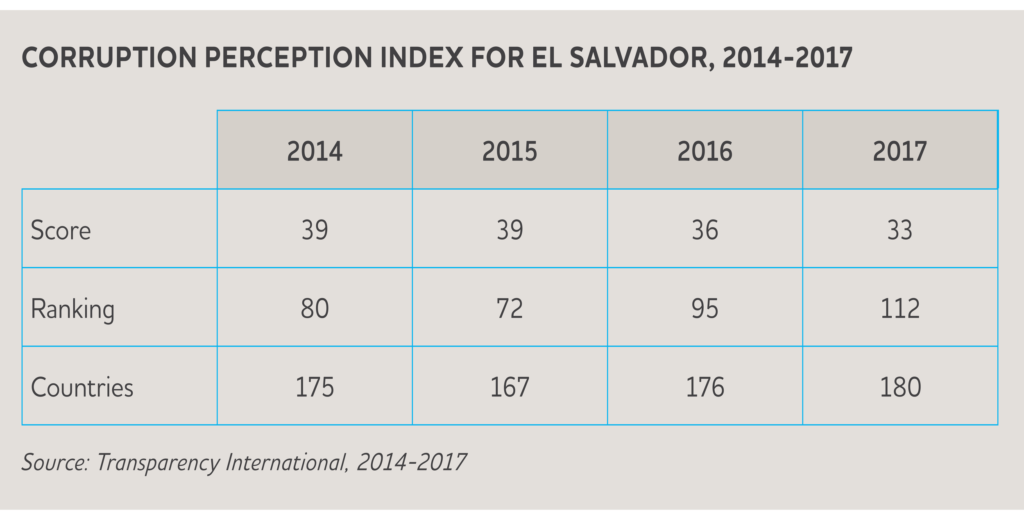

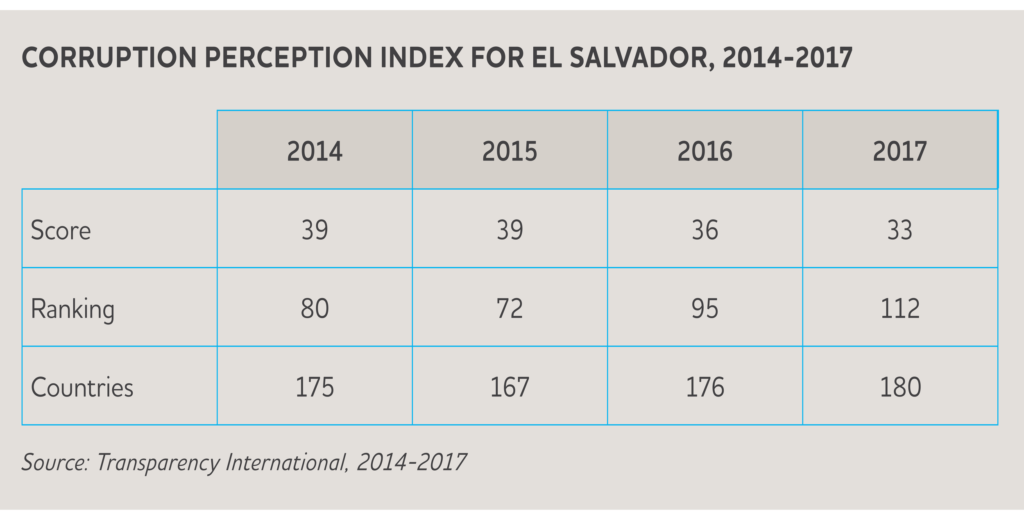

During the 2014-2017 period, El Salvador was rated extremely low in Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index, with scores between 33 to 39 points (Transparency International uses a scale between 0 and 100, 0 meaning highly corrupt, and 100 meaning non-corrupt). This is well below the annual average reported by the international organization. The accompanying table shows El Salvador’s performance in this index.

Public opinion polls show the main problems that citizens identify in the country are crime and the economy. However, since 2013, the proportion of Salvadorans who identify corruption as the country’s main problem has continuously grown. This demonstrates a greater awareness about corruption among the public, as illustrated in the accompanying graph.

Public opinion polls show the main problems that citizens identify in the country are crime and the economy. However, since 2013, the proportion of Salvadorans who identify corruption as the country’s main problem has continuously grown. This demonstrates a greater awareness about corruption among the public, as illustrated in the accompanying graph.

EL SALVADOR / Areas of progress

3.2

Scope and Implementation of Legislation to Combat Corruption

The oldest and most problematic secondary legislation in recent years is the 1959 Law on Illicit Enrichment of Public Officials and Employees. There is a delay regulating actions that may constitute acts of corruption, especially regarding asset declaration and illicit enrichment. The outdated law still levies fines and infractions in colones, a currency that El Salvador has not used since 2001. The law establishes fines which range from $11.43 to a maximum of $1,142.86.

El Salvador made strides in establishing regulations allowing authorities to seize illegally obtained assets and re-purpose them for state use. In 2017, the Constitutional Chamber of the Supreme Court overruled a reform adopted by the Congress that sought to put in place a 10-year statute of limitations for asset seizures and recovery.

EL SALVADOR / Areas of progress

3.3

Advancements in Criminal Investigations

Between 2014 and 2017, the government received complaints for 5,004 corruption related cases. Of these cases, 565 resulted in a dismissal, with the court suspending criminal proceedings due to a lack of evidence.

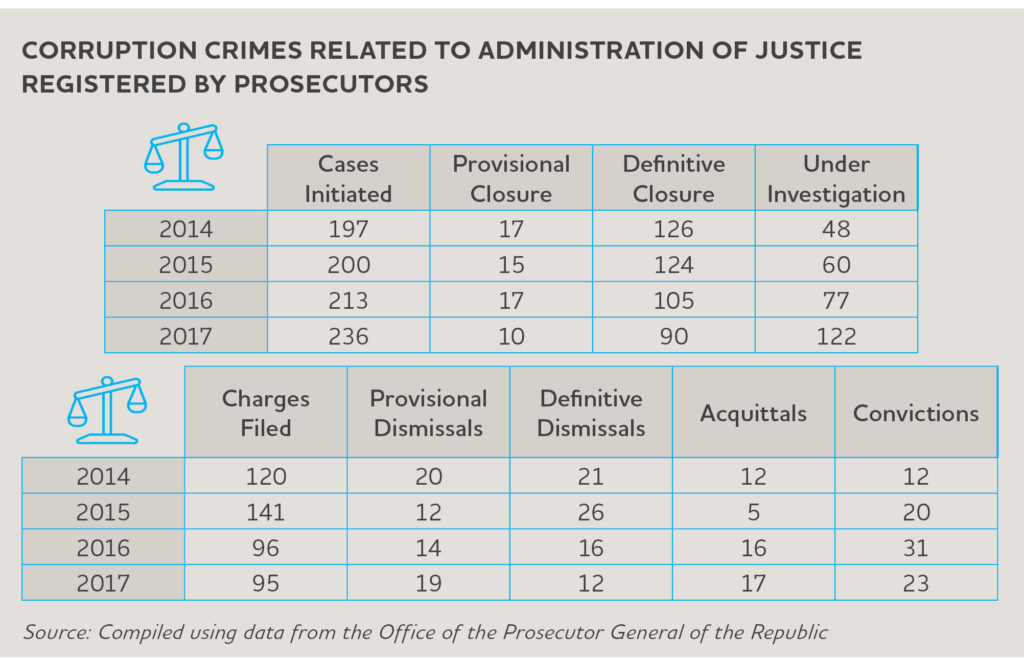

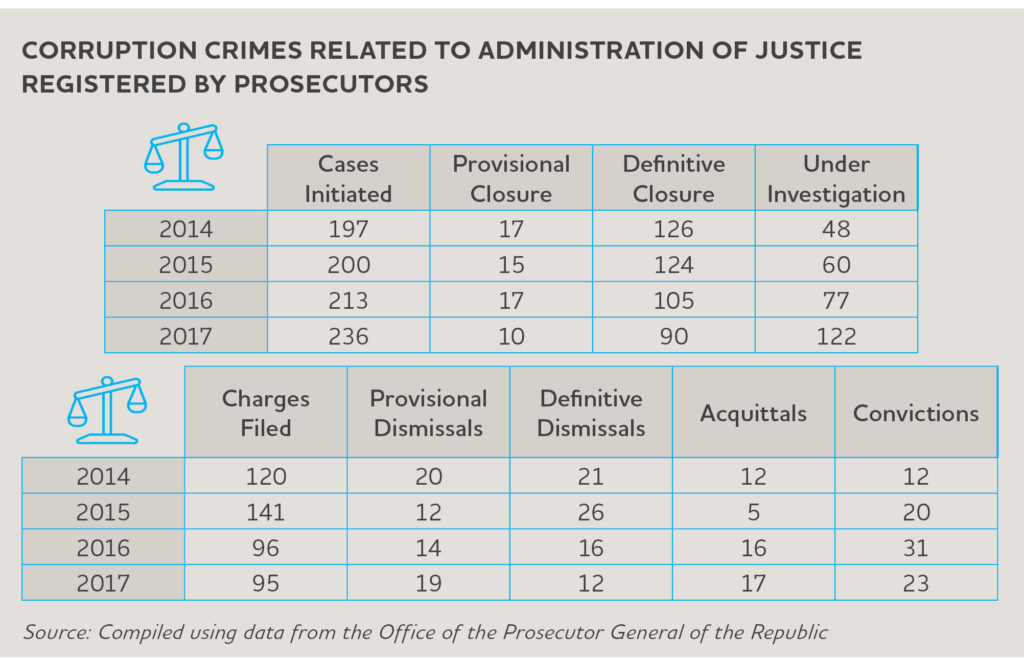

Between 2014 and 2015, the Public Prosecutor’s Office opened investigations into 846 cases involving crimes related to the administration of justice, 452 of which went to trial. Prosecutors obtained a conviction in 86 cases. During the 2014-2017 period, 140 cases did not advance in court due to lack of evidence and resulted in some type of dismissal.

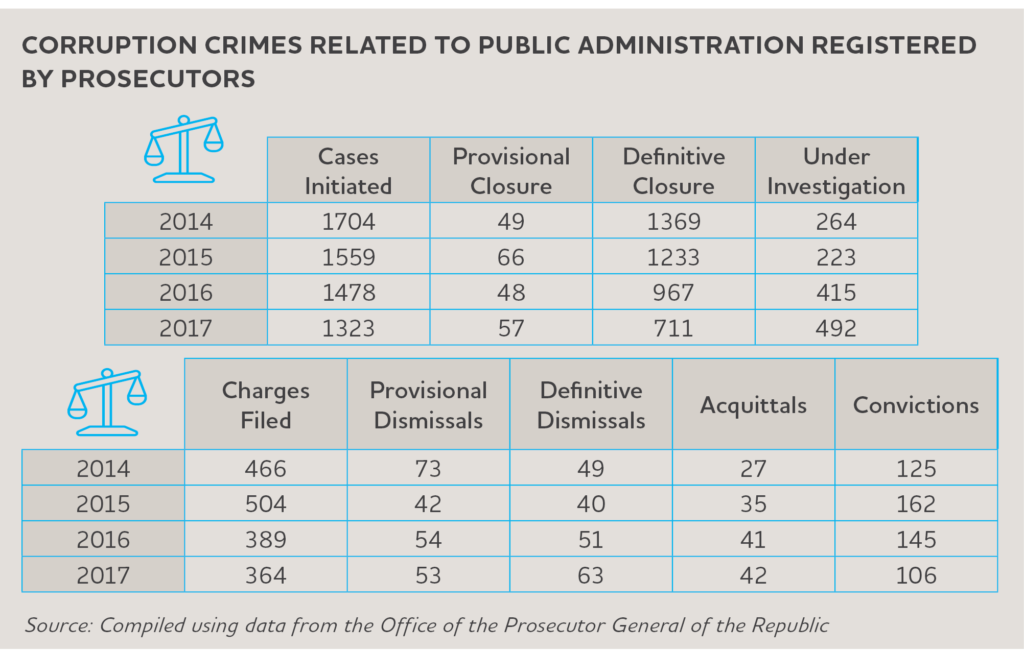

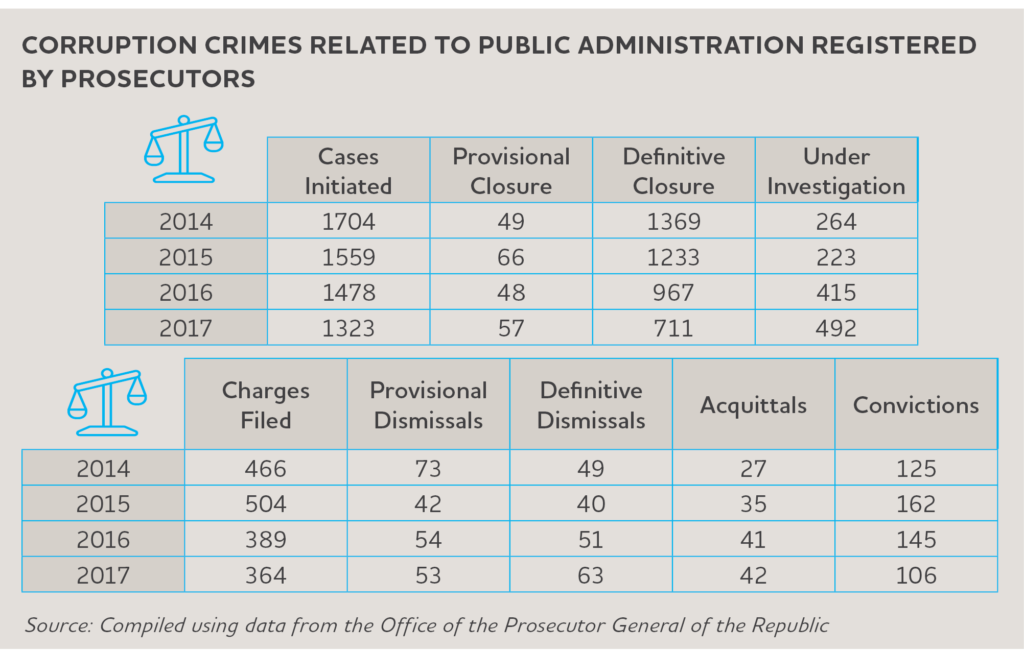

During the same period, authorities initiated investigations of 6,064 cases of alleged corruption in public administration, 1,723 of which went to trial. There were 538 convictions and 145 acquittals.

The crimes with the most number of acquittals are trafficking of prohibited objects in prison (92), bribery in exchange for committing criminal offense (12), peculation (7), and arbitrary acts (7), which together represent 81.4% of acquittals. No convictions were obtained for crimes of exaction, embezzlement, and illicit enrichment.

During the same period, authorities initiated investigations of 6,064 cases of alleged corruption in public administration, 1,723 of which went to trial. There were 538 convictions and 145 acquittals.

The crimes with the most number of acquittals are trafficking of prohibited objects in prison (92), bribery in exchange for committing criminal offense (12), peculation (7), and arbitrary acts (7), which together represent 81.4% of acquittals. No convictions were obtained for crimes of exaction, embezzlement, and illicit enrichment.

The Monitor was unable to obtain data from the judiciary, since, according to the Office of Information and Response of the Judiciary, the national trial courts stopped producing statistics of convictions and acquittals by type of crime.

The Monitor was unable to obtain data from the judiciary, since, according to the Office of Information and Response of the Judiciary, the national trial courts stopped producing statistics of convictions and acquittals by type of crime.

EL SALVADOR / Areas of progress

3.4

Functioning of Oversight Bodies

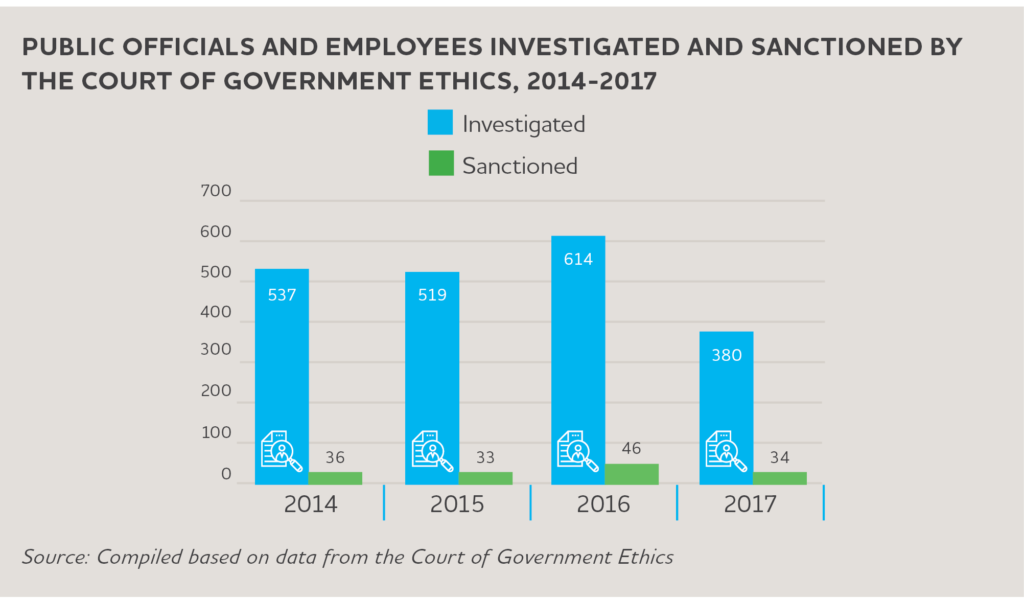

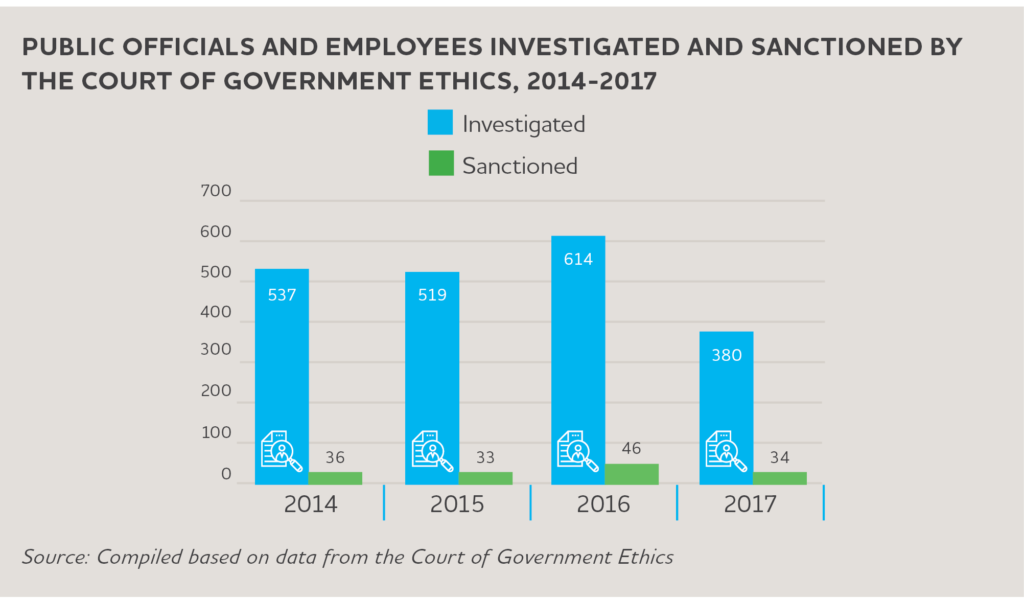

From 2014 to 2017, a total of 2,050 civil servants and public employees were investigated for violations of the Government Ethics Law. Of these, the courts only issued penalties for 7.3 percent (149 people).

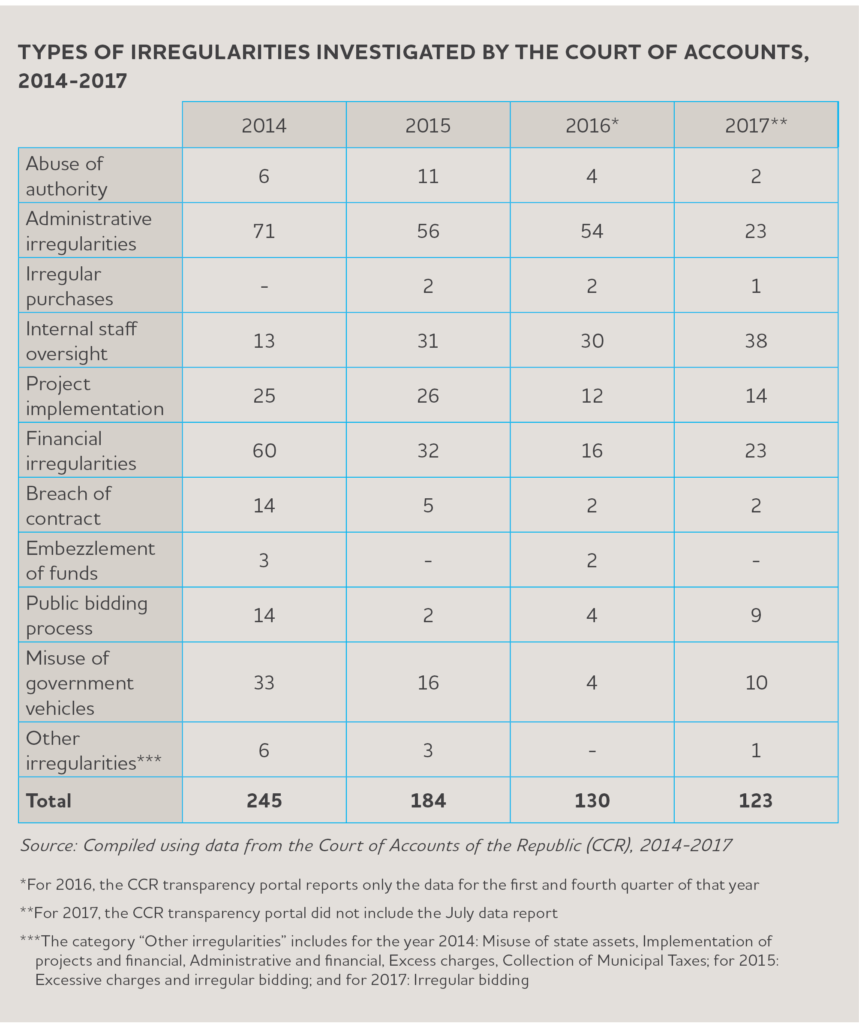

The Court of Accounts, the entity charged with auditing public funds, is one of the public agencies with the least amount of information publicly available concerning the investigations and procedures it carries out. The information available shows that the court received 682 complaints of irregularities between 2014 and 2017, mostly involving administrative and financial issues or irregularities concerning internal oversight of staff.

The Court of Accounts, the entity charged with auditing public funds, is one of the public agencies with the least amount of information publicly available concerning the investigations and procedures it carries out. The information available shows that the court received 682 complaints of irregularities between 2014 and 2017, mostly involving administrative and financial issues or irregularities concerning internal oversight of staff.